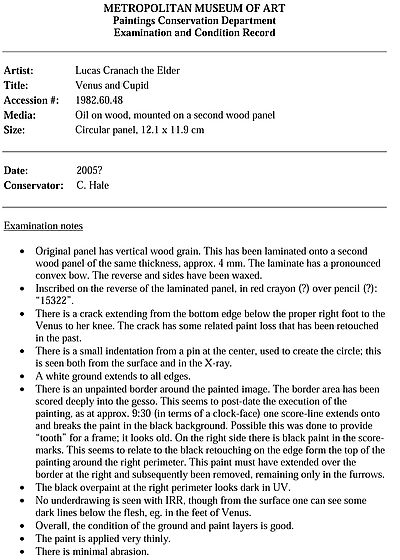

After it came to light in 1965, this painting was recognized by Dieter Koepplin as belonging to a group of small roundels by Lucas Cranach the Elder that depict various biblical, mythological, historical, and portrait subjects.[1] The example of Italian medals and circular plaquettes and the work of the medalist Hans Schwarz in Augsburg and Nuremberg may have inspired Cranach to choose a round format.[2] The production of these paintings appears to have been limited to just a few years; the dated examples are almost exclusively from 1525, and none is dated later than 1527.[3] Although the Metropolitan Museum’s panel bears no date, it clearly belongs to the same moment.[4] In design and execution, this Venus is very close to Eve in the artist’s Fall of Man tondo of 1525 (fig. 45). Also similar to that panel is the crisscross scoring at the edges beyond the image area, which may have been applied to provide the surface with enough tooth to anchor a frame.[5] Further support for the dating of the present work is provided by Cranach’s Venus and Cupid in rectangular format, dated 1525, at Compton Verney, Warwickshire, which has a similar composition showing Cupid perched on a stone block.[6]

The austere setting derives from Cranach’s first painted treatment of the theme, the large Venus and Cupid of 1509 (State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg).[7]

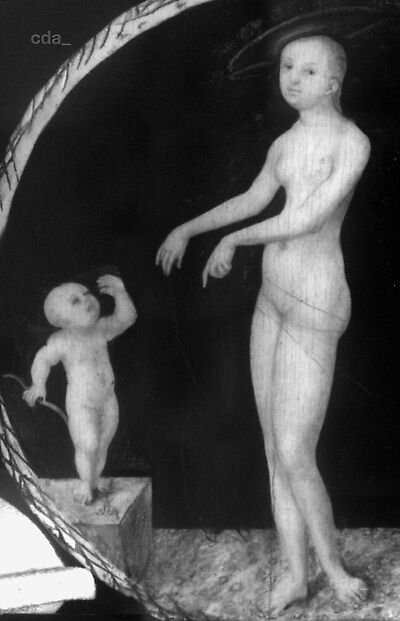

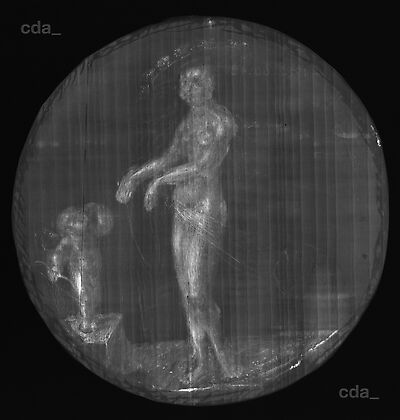

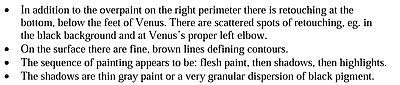

The Museum’s tondo is remarkable for its confident, efficient, and apparently very rapid brushwork. The speed of execution is suggested by the way the base flesh color was initially brushed beyond the final outlines of the figures, as is visible in the X-radiograph (fig. 46). As was common practice in the Cranach workshop, the final silhouettes were then defined using the black background color, which overlaps the edges of the roughed-in flesh paint.[8] The flesh was modeled with thin, economically applied glazes, and the contours of interior forms were sketched in with tiny strokes of brown. The realization of complex and visually convincing forms by minimal means, apparently at great speed, supports the attribution to Cranach himself.

The iconography of Venus and Cupid in the present work represents a change from Cranach’s earliest versions of the subject. In the 1509 Venus and Cupid and a woodcut from about the same year, Cupid is armed and draws his bow, but Venus subdues him with a downward gesture of her right hand, thus conveying a message of restraint of carnal desires.[9] In the Saint Petersburg painting the admonitory intent is made explicit in an inscription that reads, “Avoid Cupid’s lust with all your might, that your breast not be possessed by Venus.”[10] Later variants of the composition abandon Venus’s restraining gesture. In the Metropolitan Museum’s panel and certain others, including the version of about 1520 – 25 in the Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, and one of about 1530 in the Gemäldegalerie, Berlin, the goddess’s supremacy over Cupid is implied by her inattention to him.[11] In the present work, this is emphasized by the direction of her gaze away from Cupid. That her aloofness has effectively disarmed her son is suggested by the lack of arrows for his bow. Raising a hand to his face, his lips slightly parted, he appears to call in vain for his mother’s attention. Here, the moralism with which Cranach inaugurated the theme in 1509 is deemphasized in favor of offering Venus’s nonchalance and Cupid’s dismay for the viewer’s amusement. The harmlessness and humor of the scene are fully consonant with its diminutive size, which requires that it be studied at close range. Only in paintings showing Cupid stealing honey from a beehive, a popular theme first treated about 1526, did Cranach reintroduce a strong moralizing element in his Venus and Cupid repertoire (cat. 20).[12]

[1] Koepplin in Basel 1974, vol. 1, pp. 275 – 80, 295, 296 – 97, nos. 177 – 78, 182 – 83, 184, 185, 186, pl. 9, and figs. 139 – 41, 143 – 50, vol. 2, pp. 642, 775 – 76, n. 78. The following examples are known: The Fall of Man, 1525, Kurpfälzisches Museum, Heidelberg; Judith with the Head of Holofernes and Two Attendants, 1525, Gustav Rau Collection, UNICEF Germany, on deposit in the Arp Museum Bahnhof Rolandseck, Remagen; Virgin and Child, 1525, Wittelsbacher Ausgleichsfonds, Schloss Berchtesgaden (Friedländer and J. Rosenberg 1978, p. 101, no. 158); Martin Luther and Katharina von Bora, 1525, Kunstmuseum Basel (Friedländer and J. Rosenberg 1978, p. 107, nos. 187 – 88, 189A, B, E, 190A, B, E); Friedrich III, the Wise, 1525, and Johann I, the Constant, 1525, Staatliche Kunsthalle Karlsruhe (Friedländer and J. Rosenberg 1978, p. 105, nos. 179D – E); Cardinal Albrecht of Brandenburg, 1526, private collection; Ideal Portrait of a Woman, 1527 (date perhaps altered from 1525: see note 5 below), Staatsgalerie Stuttgart (Friedländer and J. Rosenberg 1978, p. 104, no. 174); Nymph of the Spring, ca. 1525 – 27, Kunstsammlungen der Veste Coburg, Coburg (Friedländer and J. Rosenberg 1978, p. 116, no. 232C); Lucretia, ca. 1525 – 27, formerly Grigori Stroganov Collection, Rome (Friedländer and J. Rosenberg 1978, p. 117, no. 240E); Ideal Portrait of a Woman, ca. 1525 – 27, Musée Granet, Donation J.-B.de Bourguignon, Aix-en-Provence (Friedländer and J. Rosenberg 1978, p. 104, no. 171B).

[2] Koepplin in Basel 1974, vol. 1, pp. 276, 278, vol. 2, p. 654, under no. 566; Schwarz-Hermanns 2007, pp. 128 – 30. On Cranach’s probably direct knowledge of Italian plaquettes, see Armin Kunz and Guido Messling in Brussels and Paris 2010 – 11, pp. 151 – 53, nos. 85 – 88 (with references to earlier literature). A circular plaquette attributed to Moderno on the theme of Venus and Cupid exists (see Bange 1922, no. 501, ill.; Koepplin in Basel 1974, vol. 2, p. 654, no. 566), but it did not supply the composition that Cranach used for the New York roundel. On Hans Schwarz, see Kastenholz 2006. For discussions of the rise of medals and small relief sculpture in Germany, see Grotemeyer 1957; J. C. Smith 1994, pp. 270 – 303, 321 – 57; J. C. Smith 2004. On collecting them, see J. C. Smith 1994, pp. 303 – 16; Lewis 2008, pp. 129 – 35. Douglas Lewis kindly suggested to the author (email, February 14, 2008, curatorial files, Department of European Paintings, MMA) that the stone plinth motif could derive from the bronze plaquette Sleeping Cupid by the Vicentine Master of 1507, on which see Lewis 2008, pp. 130 – 32, fig. 3.

[3] The date 1527 inscribed on the Ideal Portrait of a Woman in the Staatsgalerie Stuttgart may have been altered from 1525; see Koepplin in Basel 1974, vol. 1, pp. 296 – 97, no. 184; Rettich, Klapproth, and Ewald 1992, pp. 95 – 96, ill.

[4] The date of about 1530 given in Friedländer and J. Rosenberg 1978, p. 119, no. 249, is too late.

[5] Such marks are present on other roundels in the group, for example, the Nymph of the Spring in Coburg (image under CDA ID/Inv. No. DE_KSVC_M161, in Cranach Digital Archive, http://www.lucascranach.org/digitalarchive.php [accessed May 2, 2012]) and the Lucretia formerly owned by Grigori Stroganov (photograph in Sperling File, Department of European Paintings, MMA).

[6] See Jeremy Warren in Compton Verney 2010, p. 56, no. 25, ill.

[7] Friedländer and J. Rosenberg 1978, p. 72, no. 22, ill.; Bierende 2002, pp. 217 – 19.

[8] See Heydenreich 2007b, pp. 207 – 8.

[9] For the woodcut, see Hollstein 1954 – , vol. 6 (1959), p. 81, no. 105; Koepplin in Basel 1974, vol. 1, pl. 15, vol. 2, pp. 644 – 50, no. 555; Armin Kunz in Brussels and Paris 2010 – 11, pp. 187 – 88, no. 96, ill. The 1506 date on the woodcut is generally agreed to be a predating meant to claim priority in the invention of the chiaroscuro technique used for some of the impressions.

[10] “Pelle cvpidineos toto conamine lvxvs / Ne tua possideat pectora ceca venvs” (cited in Friedländer and J. Rosenberg 1978, p. 72, no. 22).

[11] For the Stockholm panel, see Koepplin in Basel 1974, vol. 2, pp. 654 – 55, no. 567, fig. 320; Görel Cavalli-Bjorkman in Stockholm 1988, p. 66, no. 50, ill. For the one in Berlin, see Friedländer and J. Rosenberg 1978, no. 241, ill.

[12] The first example of many is the Venus and Cupid the Honey Thief (Cupid Complaining to Venus) of about 1526 in the National Gallery, London (Friedländer and J. Rosenberg 1978, p. 119, no. 246L; Caroline Campbell in London 2007, pp. 80 – 83, no. 2, ill.). Mary Sprinson de Jesús (in Baetjer et al. 1986, p. 159) noted that Cupid’s raised arm in the Museum’s roundel may have been transposed from a honey-thief composition in which Cupid lifts his arm to shoo away bees.

[Waterman, Cat. New York 2013, 52, 53, 285, 286, no. 10]