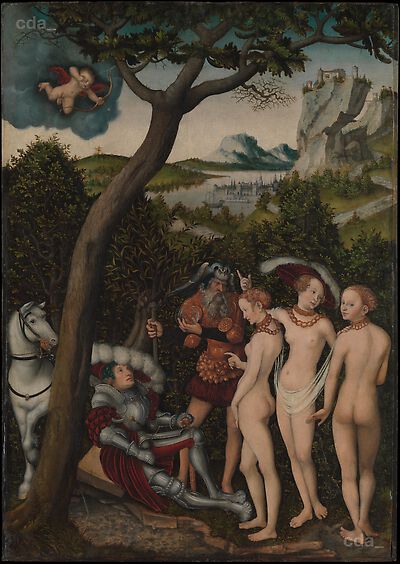

In the mid-twelfth century, the French poet Benôit de Saint-Maure wrote the Roman de Troie (Romance of Troy), which was based on the purportedly eyewitness account of the destruction of the city by Dares Phrygius, a Trojan priest of Hephaestus.[1] Another well-known and widely disseminated romance was Guido delle Colonne’s late thirteenth-century Historia Destructionis Troiae (History of the Destruction of Troy).[2] Cranach must have known either Dares’s account[3] or the medieval romances,[4] for his Judgment of Paris follows two distinctive features of their texts: Paris as a hunter, not a shepherd as in other ancient sources,[5] and Paris’s encounter with Mercury and the three goddesses in a dream. Guido’s text also provides other specific details adopted by Cranach: the setting in the “loneliest part of these groves” of Mount Ida, the horse tied near a tree, and the proviso that the goddesses present themselves naked so that Paris might “consider the individual qualities of their bodies for a true judgment.”[6]

Cranach’s depiction of the theme was also influenced by early prints. An engraving of about 1460 by the Master of the Banderoles shows the three naked goddesses, modestly covering themselves with diaphanous veils, and Mercury attempting to awaken a slumbering Paris in a lush wooded landscape (fig. 47).[7] A woodcut illustration of the scene in the 1502 Wittenberg edition of Dares Phrygius’s Bellum Troianum (Trojan War)[8] also provided a visual precedent for Cranach’s first image on the theme, a signed and dated woodcut of 1508 in which the goddesses have just disrobed (fig. 48). For the contrasting front and back poses of two of them, the artist was inspired by Jacopo de’ Barbari’s Victory and Fame, an engraving of 1498 – 1500 that circulated in Nuremberg, where de’ Barbari went in 1500 to work for Emperor Maximilian I.[9] Cranach’s woodcut in turn served as the model for at least a dozen painted versions by himself and his workshop, beginning with the artist’s panel of about 1510 (Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth) and including the present work, a considerably later adaptation of about 1528. […]

A free sketch of the composition, dated by most scholars between 1527 and 1530 (fig. 49),[10] probably served as a preliminary idea for the Museum’s painting and other close variants,[11] none of which follow the initial design exactly but simply rearrange its landscape and figural motifs. Although the three goddesses have sometimes been thought to be portraits of women at the Saxon court, [12] their faces appear too generalized for such an assertion.

Instead, they are likely based on oil sketches such as the Study of Three Female Heads of about 1530 (fig. 50), which Cranach produced for use in a number of his paintings, making slight adjustments to the facial features in each work to give the impression of different individuals.[13]

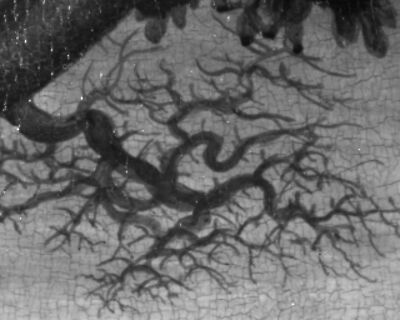

The remnants of Cranach’s insignia, a winged serpent, appear below the feet of the leftmost goddess, but Richard Förster failed to notice them when he stated in 1899 that the painting was neither signed nor dated.[14] The same year, Karl Woermann listed it among unauthenticated works by Cranach and his workshop,[15] and Max J. Friedländer deemed it a middling, perhaps autograph work. Others, including Eduard Flechsig, assigned it to Cranach’s son Hans.[16]

After the painting was exhibited in Nuremberg in 1922 – 24 and came up for auction in 1928, Friedländer viewed it more positively as a genuine and accomplished work.[17] As a result, the Metropolitan Museum acquired the painting, and Harry Wehle published the first substantial study of the picture since Förster’s initial article.[18] Wehle convincingly argued for a date around 1528, comparing the work favorably with the version of that date in the Kunstmuseum Basel.[19] Confusion developed when Friedländer and Jakob Rosenberg (later followed by Charles Kuhn and Hans Posse) wrote that the painting is signed and dated 1529, an error corrected in the second edition of their monograph.[20] More recently, Burton Dunbar noted that the poses and attitudes of the goddesses here served as a source for the figures in The Three Graces (Nelson-Atkins Museum, Kansas City), which is dated 1535.[21] He argued that the goddess pointing upward in that work must derive from the earlier Metropolitan’s Venus, since without Cupid above there is no iconographic reason for this gesture.

One of the most intriguing questions concerning Cranach’s Judgment of Paris is its deeper meaning in the context of its own time. The theme was popular with German humanists,[22] and Franz Matsche has argued for a humanist understanding of Paris’s dilemma in the vein of the philosophy of life of Conrad Celtis and his followers.[23] This concerned the difficult choice of which type of life to lead: the vita contemplativa, the vita activa, or the vita voluptaria. Although the contemplative life was the most highly regarded, its arduousness was acknowledged, as was the fact that knowledge is achieved primarily through making errors.

Hanne Kolind Poulsen viewed Matsche’s interpretation in the light of Protestantism, arguing that the Christian’s difficulty in choosing a way of life, in finding salvation, ultimately depends on divine grace.[24] This dilemma was the subject of the commencement speech given by the Greek scholar Nicolaus Marschalk to the first graduating class of the University of Wittenberg in 1503.[25] Railing against Paris’s misguided judgment, Marschalk urged students to be wary of Venus’s power and of women in general and instead to follow Minerva, who “offers thrift, a sense of shame, modesty, chastity, [and] industry . . . the stepping stones to the attainment of learning, of wisdom and the remaining virtues, and of the highest happiness.”[26] Just one year after Marschalk’s oration, a student of his at Wittenberg, Hermann Trebelius, published a warning against Venus’s power in a preface to a poem on the Judgment of Paris by the Neapolitan humanist Johannes Baptista Cantalicius.[27] The rather crude woodcut illustrating this publication was an important antecedent to Cranach’s first woodcut of the subject in 1508. Seen in this context, Cranach’s woodcut and his paintings on the theme would have an admonitory function, warning against the wiles of woman, a subject further developed in contemporary Weibermacht (power of women) images, such as Cranach’s Samson and Delilah (cat. 12). Dieter Koepplin argued that Marschalk’s moralizing interpretation, based on the writings of Fulgentius, would have been the source for Cranach’s realization of the story.[28]

A challenge to the humanist interpretation was offered by Berthold Hinz.[29] Hinz argued that, for such an interpretation to be valid, the goddesses would have to be clearly identifiable in order to link them with the alternative ways of life, a precondition that does not apply to Cranach’s depiction. Instead, Hinz regarded the similarity of the goddesses as an attempt to “provoke a play of ideas and meanings”[30] — and perhaps to introduce an element of ambiguity and the possibility of multiple interpretations — which has little to do with the rigorous humanism found in images by contemporary artists such as Dürer and Burgkmair.[31]

The Judgment of Paris theme may also be understood in a social-historical rather than philosophical context. Inge El-Himoud-Sperlich has interpreted Cranach’s Paris paintings as decorations for bedroom chambers, noting that he is documented as having painted such a scene for the bridal chamber of Margareta von Anhalt, who married Duke Johann of Saxony in 1513. El-Himoud-Sperlich suggested that these works were meant not as warnings to men against making wrong decisions, as Koepplin theorized, but instead as confirmations for women that their husbands had renounced what advantages might be gained by marrying a smarter (Minerva) or wealthier (Juno) mate, instead choosing for love and beauty (Venus).[32]

Koepplin, in a more recent revisiting of the Judgment of Paris theme, examined a few troubling issues, namely, Cupid’s pointing his arrow at Venus instead of at Paris and the nearly indistinguishable appearance of the goddesses. Regarding the former, Koepplin claimed that the positioning of Cupid emphasizes the power of the goddess instead of the weakness of Paris and that the informed viewer would realize that his arrow ultimately reaches Paris.[33] As for the sameness of the goddesses, Koepplin noted that, althougha moralizing message is certainly present, their resemblance serves Cranach’s desire to introduce new possibilities of meaning, such as the positive aspects of Venus’s power if the painting were to be used as a marriage picture.[34]

Equally interesting but also controversial was Helmut Nickel’s interpretation of the Museum’s Judgment of Paris as alchemical in meaning.[35] Nickel understood the painting as representing the three stages of the so-called Great Work, that is, the conversion of base material into gold, and the three goddesses as personifications of the stages. His extremely meticulous argument has yet to be supported or refuted by other scholars on the basis of subsequent discussions of alchemy.

Clearly, there is a rich array of possible meanings for the Judgment of Paris theme. Its popularity, evidenced by the significant number of surviving examples, perhaps attests to multivalent interpretations in Cranach’s own time.

[1] Frazer 1966. For a survey of the transformations of this story in art, see M. Rosenberg 1930. See also R. Förster 1899, pp. 267 – 69.

[2] See Colonne 1936 (ed.); Colonne 1970 (ed.); Colonne 1974 (ed.).

[3] Perhaps from the 1502 Wittenberg edition of Dares the Phrygian’s Bellum Troianum.

[4] R. Förster 1899, pp. 267 – 69.

[5] Lucian’s telling of the tale, for example, has Paris as a shepherd. See Lucian 1921(ed.), p. 393.

[6] Colonne 1974 (ed.), p. 60.

[7] Lehrs 1908 – 34, vol. 4 (1921), nos. 90, 91. For another engraving of The Judgment of Paris by the Master of the Banderoles, see Dieter Koepplin in Basel 1974, vol. 2, pp. 624 – 25.

[8] Koepplin attributed this print to an anonymous Erfurt or Wittenberg artist and discussed it as the basis for Cranach’s 1508 woodcut. See Koepplin in Basel 1974, vol. 1, p. 211, vol. 2, pp. 622 – 24, no. 528a, ill. vol. 1, p. 213, fig. 116.

[9] Ferrari 2006, pp. 120 – 21, no. 9. See also Bierende 2002, pp. 209 – 12.

[10] J. Rosenberg 1960, p. 23, no. 46; Thöne 1965, ill. pp. 78 – 79; du Colombier 1966; Dieter Koepplin in Basel 1974, vol. 2, p. 494, no. 345; Biedermann 1981, p. 312 (who dates the drawing earlier, to about 1525). Michael Hof bauer (2010, pp. 384 – 85, no. 189) attributed the drawing to Cranach the Younger.

[11] Other variants include the following: listed by Friedländer and J. Rosenberg 1978, now Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, ca. 1512 – 14 (no. 41); Seattle Art Museum, ca. 1516 – 18 (no. 118); Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen, dated 1527 (no. 252); Kunstmuseum Basel, dated 1528 (no. 253); Staatliche Kunsthalle Karlsruhe, dated

1530 (no. 255); Anhaltische Gemäldegalerie Dessau (lost in 1945), ca. 1535 (no. 256); Steiermärkisches Landesmuseum Joanneum, Graz, ca. 1530 – 35 (no. 257); Saint Louis Art Museum, ca. 1537 (no. 258); Schloss Museum Gotha, after 1537 (no. 409); Collection of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, Hampton Court Palace, after 1537

(no. 409a); Gemäldegalerie, Berlin, after 1537 (no. 409a); Museum zu Allerheiligen, Schaffhausen (not in Friedländer and J. Rosenberg 1978).

[12] El-Himoud-Sperlich 1977, pp. 56, 63.

[13] This drawing is most closely related to a painting of the Three Graces formerly in an English private collection (Friedländer and J. Rosenberg 1978, p. 119, no. 251A); see Brinkmann in Frankfurt and London 2007 – 8, p. 292, no. 85. See also Hof bauer 2010, pp. 168 – 69, no. 52.

[14] R. Förster 1899, p. 267. Förster may not have seen these because of overlying restoration.

[15] Woermann in Dresden 1899, pp. 78 – 79, no. 121.

[16] Friedländer 1899, p. 246; Flechsig 1900, p. 282, no. 121.

[17] Friedländer, cable to the Metropolitan Museum, October 24, 1928 (curatorial files, Department of European Paintings, MMA).

[18] Wehle 1929 – 30.

[19] Ibid., p. 9; repeated by Wehle and Salinger 1947, p. 201.

[20] Friedländer and J. Rosenberg 1932, p. 68, no. 209; Kuhn 1936, p. 38, no. 98; Posse 1943, p. 61, no. 86; Friedländer and J. Rosenberg 1978, p. 120, no. 254.

[21] Dunbar 2005, p. 85.

[22] Koepplin in Basel 1974, vol. 2, pp. 613 – 31.

[23] Matsche 1996, pp. 59 – 67.

[24] Poulsen 2003, p. 140. This interpretation lacks the support of texts about the Paris myth written by sixteenth-century theologians.

[25] Marschalk 1503/1967, p. 37.

[26] Ibid., p. 41; see also Koepplin in Basel 1974, vol. 2, p. 616.

[27] See Koepplin in Basel 1974, vol. 1, p. 211, vol. 2, pp. 622 – 24, no. 528a. The accompanying woodcut also appeared in an edition of Dares the Phrygian’s Bellum Troianum published in Wittenberg in 1502 (see Bierende 2002, pp. 205 – 6; see also discussion and note 13 above).

[28] See Fabius Planciades Fulgentius, Mitologiarus libri tres (in Fulgentius 1898 [ed.], pp. 3 – 80), for his moralizing, allegorical interpretation of the Paris myth; Koepplin in Basel 1974, vol. 2, p. 622. For a different theory, based on the Ficinian notion of the difficulty of moral decision-making and the necessity of making errors, see Matsche 1994; Matsche 1996.

[29] Hinz 1994, p. 179; see also Hinz 2005.

[30] Hinz 1994, pp. 177 – 78.

[31] Bierende (2002, p. 384, n. 84) rejects Hinz’s point of view.

[32] El-Himoud-Sperlich 1977, pp. 72 – 73. In support of her theory, El-Himoud-Sperlich argued that Cupid in the Museum’s painting is aiming his arrow at the leftmost goddess, whom she identified as Venus (although clearly Cupid aims at the center goddess, who is more likely Venus). She thus regards Venus’s apparent covering of her pudenda from Paris’s view as a sign of chaste courtship.

[33] Koepplin 2003b, p. 52.

[34] Ibid., p. 54.

[35] Nickel (Helmut) 1981, pp. 123 – 27, 129.

[Ainsworth, Cat. New York 2013, 54-58, 286, No. 11]