| Exhib. Cat. Vienna 2022 |

75, 76, 140 |

001 |

Fig. p. 75 |

| Editor | Guido Messling, Kerstin Richter |

|---|

| Title | Cranach. Die Anfänge in Wien [Winterthur, Sammlung Oskar Reinhart, 12.03-12.06.2022; Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum, 21.06-16.10.2022] |

|---|

| Place of Publication | Munich |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 2022 |

|---|

|

| Bonnet, Görres 2015 |

14-15 |

2 |

p. 15 |

| Author | Anne-Marie Bonnet, Daniel Görres |

|---|

| Title | Lucas Cranach d. Ä. - Maler der Deutschen Renaissance |

|---|

| Place of Publication | Munich |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 2015 |

|---|

|

| Exhib. Cat. Frankfurt 2014 |

92-93 |

33 |

p. 93 |

| Editor | Stefan Roller, Jochen Sander |

|---|

| Title | Fantastische Welten. Albrecht Altdorfer und das Expressive in der Kunst um 1500, [Frankfurt, Städel Museum, 5 Nov 2014 - 8 Feb 2015; Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum, 17 Mar 2015 - 14 Jun 2015] |

|---|

| Place of Publication | Munich |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 2014 |

|---|

|

| Bonnet, Kopp-Schmidt, Görres 2010 |

130 |

No. 2 |

Plate |

| Author | Anne-Marie Bonnet, Gabriele Kopp-Schmidt, Daniel Görres |

|---|

| Title | Die Malerei der deutschen Renaissance |

|---|

| Place of Publication | Munich |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 2010 |

|---|

|

| Exhib. Cat. Brussels 2010 |

103-104 |

5 |

|

| Editor | Bozarbooks & Lannoo, Guido Messling |

|---|

| Title | Die Welt des Lucas Cranach. Ein Künstler im Zeitalter von Dürer, Tizian und Metsys [anlässlich der Ausstellung "Die Welt des Lucas Cranach", Palast der Schönen Künste, Brüssel, 20. Oktober 2010 - 23. Januar 2011] |

|---|

| Place of Publication | Brussels |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 2010 |

|---|

|

| Kunz 2010 |

82 |

|

|

| Author | Armin Kunz |

|---|

| Title | Anmerkungen zu Cranach als Graphiker |

|---|

| Publication | in Guido Messling, ed., Die Welt des Lucas Cranach. Ein Künstler im Zeitalter von Dürer, Tizian und Metsys, Exhib. Cat. Brussels |

|---|

| Place of Publication | Brussels |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 2010 |

|---|

| Pages | 80-93 |

|---|

|

| Exhib. Cat. Frankfurt 2007 |

116-117 |

2 |

p. 117 |

| Editor | Bodo Brinkmann |

|---|

| Title | Cranach der Ältere, [Frankfurt, Städel Museum, 23 Nov 2007 - 17 Feb 2008] |

|---|

| Place of Publication | Ostfildern |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 2007 |

|---|

|

| Heydenreich 2007 A |

47 |

|

Figs. 16, 17 |

|

|

| Heydenreich 2007 B |

35 |

|

|

| Author | Gunnar Heydenreich |

|---|

| Title | "... dass Du mit wunderbarer Schnelligkeit malest". Virtuosität und Effizienz in der künstlerischen Praxis Lucas Cranachs d. Ä. |

|---|

| Publication | in Bodo Brinkmann, ed., Cranach der Ältere, Exhib. Cat. FrankfurtA |

|---|

| Place of Publication | Ostfildern |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 2007 |

|---|

| Pages | 29-47 |

|---|

|

| Seipel et al. 2007 |

182 |

|

with Fig. |

| Editor | Wilfried Seipel, Cäcilia Bischoff |

|---|

| Title | Das Kunsthistorische Museum in Wien |

|---|

| Series | Prestel-Museumsführer |

|---|

| Place of Publication | Vienna |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 2007 |

|---|

|

| Stadlober 2006 |

155-164 |

|

Fig. 25 |

| Author | Margit Stadlober |

|---|

| Title | Der Wald in der Malerei und der Graphik des Donaustils |

|---|

| Series | Ars viva |

|---|

| Volume | 10 |

|---|

| Place of Publication | Vienna, Böhlau |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 2006 |

|---|

|

| Lechner 2005 |

29 |

|

Fig. 23 |

| Author | Georg Matthias Lechner |

|---|

| Title | Lucas Cranach d. Ä.. Das "Paradies" im Wiener Kunsthistorischen Museum. Landschaftsdarstellung, Bilderzählung, Hintergründe. Zum Schaffen des Künstlers um 1530 [Diplomarbeit, Universität Wien] |

|---|

| Place of Publication | [Vienna] |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 2005 |

|---|

|

| Schölzel 2005 |

197 Fn. 5 |

|

|

| Author | Christoph Schölzel |

|---|

| Title | Zeichnungen unter der Farbschicht. Zu den Unterzeichnungen von Cranachs Gemälden in der Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister und in der Rüstkammer Dresden |

|---|

| Publication | in Harald Marx, Ingrid Mössinger, Karin Kolb, eds., Cranach. Gemälde aus Dresden, Exhib. Cat. Chemnitz |

|---|

| Place of Publication | Cologne |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 2005 |

|---|

| Pages | 182-197 |

|---|

|

| Wegmann 2003 |

|

|

|

| Author | Susanne Wegmann |

|---|

| Title | Rezension von: Bierende 2002 und Heiser 2002 |

|---|

| Journal | Sehepunkte. Rezensionsjournal für die Geschichtswissenschaften |

|---|

| Issue | Jg. 3, H. Nr. 11 |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 2003 |

|---|

|

| Bierende 2002 |

16-24, 38-84, 84-108 |

|

Figs. 1, 13, 34 |

| Author | Edgar Bierende |

|---|

| Title | Lucas Cranach d.Ä. und der deutsche Humanismus. Tafelmalerei im Kontext von Rhetorik, Chroniken und Fürstenspiegeln |

|---|

| Place of Publication | Berlin |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 2002 |

|---|

|

| Heiser 2002 |

25-27, 34, 39, 42, 54, Fns. 214, 257; 88-89, Fn. 559; 93, 108, 111, 134 |

|

Figs. 9, 79, 110, 111 |

| Author | Sabine Heiser |

|---|

| Title | Das Frühwerk Lucas Cranachs des Älteren. Wien um 1500 - Dresden um 1900 |

|---|

| Series | Neue Forschungen zur Deutschen Kunst |

|---|

| Volume | 6 |

|---|

| Place of Publication | Berlin |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 2002 |

|---|

|

| Exhib. Cat. Wiener Neustadt 2000 |

|

No. 101 |

|

| Author | Christa Angermann |

|---|

| Editor | Kulturamt der Stadt Wiener Neustadt |

|---|

| Editing | Norbert Koppensteiner, Ingrid Riegler |

|---|

| Title | Maximilian I. Der Aufstieg eines Kaisers von seiner Geburt bis zur Alleinherrschaft 1459 - 1493 |

|---|

| Place of Publication | Wiener Neustadt |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 2000 |

|---|

|

| Anzelewsky 1999 |

125, 128, 132-133 |

|

Fig. 4 |

| Author | Fedja Anzelewsky |

|---|

| Title | Studien zur Frühzeit Lukas Cranachs d.Ä. |

|---|

| Journal | Städel-Jahrbuch |

|---|

| Issue | 17 |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 1999 |

|---|

| Pages | 125-144 |

|---|

|

| Exhib. Cat. Eisenach 1998 |

96, 97, 103 |

No. 11.1 |

Figs. 11.1a-e |

| Editor | Wartburg-Stiftung, Eisenach, Fachhochschule , Ingo Sandner |

|---|

| Title | Unsichtbare Meisterzeichnungen auf dem Malgrund. Cranach und seine Zeitgenossen. Ausstellungskatalog und Tagungsband Katalogteil 1; 2: Werkstatt und Schüler Cranachs; 3: Süddeutsche Meister; 4: Albrecht Dürer und sein Kreis; 5: Rheinische Meister |

|---|

| Place of Publication | Regensburg |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 1998 |

|---|

| Pages | 229-240 |

|---|

|

| Heydenreich 1998 A |

185, 196 |

|

|

| Author | Gunnar Heydenreich |

|---|

| Title | Herstellung, Grundierung und Rahmung der Holzbildträger in den Werkstätten Lucas Cranachs d.Ä. |

|---|

| Publication | in Ingo Sandner, Wartburg-Stiftung Eisenach and Fachhochschule Köln, eds., Unsichtbare Meisterzeichnungen auf dem Malgrund. Cranach und seine Zeitgenossen, Exhib. Cat. Eisenach |

|---|

| Place of Publication | Regensburg |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 1998 |

|---|

| Pages | 181-200 |

|---|

|

| Sandner 1998 B |

84-85, 88, 90 |

|

|

| Author | Ingo Sandner |

|---|

| Title | Cranach als Zeichner auf dem Malgrund |

|---|

| Publication | in Ingo Sandner, Wartburg-Stiftung Eisenach and Fachhochschule Köln, eds., Unsichtbare Meisterzeichnungen auf dem Malgrund. Cranach und seine Zeitgenossen, Exhib. Cat. Eisenach |

|---|

| Place of Publication | Regensburg |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 1998 |

|---|

| Pages | 83-95 |

|---|

|

| Schawe 1998 |

165 |

|

|

| Author | Martin Schawe |

|---|

| Title | Das Tafelgemälde "Kreuzigung Christi" Lucas Cranachs des Älteren von 1503 |

|---|

| Publication | in Ingo Sandner, Wartburg-Stiftung Eisenach and Fachhochschule Köln, eds., Unsichtbare Meisterzeichnungen auf dem Malgrund. Cranach und seine Zeitgenossen, Exhib. Cat. Eisenach |

|---|

| Place of Publication | Regensburg |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 1998 |

|---|

| Pages | 160-166 |

|---|

|

| Stadlober 1998 |

420, 421 |

|

Fig. p. 467 |

| Author | Margit Stadlober |

|---|

| Title | Das Frühwerk Lucas Cranachs d. Ä. und Österreich - Ein Entwicklungsweg |

|---|

| Journal | Österreichische Zeitschrift für Kunst und Denkmalpflege |

|---|

| Issue | 52/2 |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 1998 |

|---|

| Pages | 414-423 |

|---|

|

| Deroo 1996 |

20-21 |

|

with Fig. |

| Author | Marc Deroo |

|---|

| Title | Lucas Cranach d. Ä. |

|---|

| Place of Publication | Paris |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 1996 |

|---|

|

| Büttner 1994 |

24 |

|

Fig. 1 |

|

|

| Exhib. Cat. Kronach 1994 |

294, 295, 328, 371 |

110 |

Fig. p. 295, Fig. p. 18 |

| Editor | Claus Grimm, Johannes Erichsen, Evamaria Brockhoff |

|---|

| Title | Lucas Cranach. Ein Maler-Unternehmer aus Franken [Festung Rosenberg, Kronach 17.05 - 21.08.1994; Museum der Bildenden Künste, Leipzig 07.09 - 06.11.1994] |

|---|

| Series | Veröffentlichungen zur bayerischen Geschichte und Kultur |

|---|

| Volume | 26 |

|---|

| Place of Publication | Augsburg, Coburg |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 1994 |

|---|

|

| Grimm 1994 |

18, 19 |

110 |

Fig. A1 |

| Author | Claus Grimm |

|---|

| Title | Lucas Cranach 1994 |

|---|

| Publication | in Claus Grimm, Johannes Erichsen, Evamaria Brockhoff, eds., Lucas Cranach. Ein Maler-Unternehmer aus Franken, Exhib. Cat. Kronach 1994 |

|---|

| Series | Veröffentlichungen zur bayerischen Geschichte und Kultur |

|---|

| Volume | 26 |

|---|

| Place of Publication | Augsburg, Regensburg |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 1994 |

|---|

| Pages | 18-43 |

|---|

|

| Hörsch 1994 |

96 |

|

|

| Author | Markus Hörsch |

|---|

| Title | Auftraggeber und Maler im Bistum Bamberg |

|---|

| Publication | in Claus Grimm, Johannes Erichsen, Evamaria Brockhoff, eds., Lucas Cranach. Ein Maler-Unternehmer aus Franken, Exhib. Cat. Kronach 1994 |

|---|

| Series | Veröffentlichungen zur bayerischen Geschichte und Kultur |

|---|

| Volume | 26 |

|---|

| Place of Publication | Augsburg, Coburg |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 1994 |

|---|

| Pages | 96-110 |

|---|

|

| Klein 1994 A |

195 |

|

Tab. 1 |

| Author | Peter Klein |

|---|

| Title | Lucas Cranach und seine Werkstatt. Holzarten und dendrochronologische Analyse |

|---|

| Publication | in Claus Grimm, Johannes Erichsen, Evamaria Brockhoff, eds.,Lucas Cranach. Ein Maler-Unternehmer aus Franken, Exhib. Cat. Kronach 1994 |

|---|

| Series | Veröffentlichungen zur bayerischen Geschichte und Kultur |

|---|

| Volume | 26 |

|---|

| Place of Publication | Augsburg, Coburg |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 1994 |

|---|

| Pages | 194-200 |

|---|

|

| Reiter 1994 |

42, Fn. 20 |

|

|

| Author | Cornelia Reiter |

|---|

| Title | Die Geschichte der Gemäldesammlung des Schottenstiftes |

|---|

| Publication | in Alfred Brogyányi, ed., Festschrift zur Eröffnung des Museums im Schottenstift |

|---|

| Place of Publication | Vienna |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 1994 |

|---|

| Pages | 39-44 |

|---|

|

| Sandner, Ritschel 1994 |

186-189 |

|

Fig. A123 |

| Author | Ingo Sandner, Iris Ritschel |

|---|

| Title | Arbeitsweise und Maltechnik Lucas Cranachs und seiner Werkstatt |

|---|

| Publication | in Claus Grimm, Johannes Erichsen, Evamaria Brockhoff, eds., Lucas Cranach. Ein Maler-Unternehmer aus Franken, Exhib. Cat. Kronach 1994 |

|---|

| Series | Veröffentlichungen zur bayerischen Geschichte und Kultur |

|---|

| Volume | 26 |

|---|

| Place of Publication | Augsburg, Coburg |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 1994 |

|---|

| Pages | 186-193 |

|---|

|

| Schütz 1991 |

92 |

|

|

| Author | Karl Schütz |

|---|

| Title | Der Sebastiansaltar Altdorfers und seine Vorzeichnungen - stilkritische und technische Aspekte |

|---|

| Journal | Kunsthistoriker, Mitteilungen des Österreichischen Kunsthistorikerverbandes |

|---|

| Issue | 8, Sondernummer: 6 |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 1991 |

|---|

| Pages | 91-95 |

|---|

|

| Locicnik 1990 |

26, 134, Fn. 16, 138-140, 176, 177-182, 183, 187-188, 193, 200, 203, 205 |

|

Figs. 79, 82 |

| Author | Raimund Andreas Locicnik |

|---|

| Title | Die Donauschule. Analyse ihrer Erforschung und Versuch einer neuen Grundlegung [Dissertation] |

|---|

| Place of Publication | Salzburg |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 1990 |

|---|

|

| Exhib. Cat. Berlin 1988 |

328 |

|

|

| Editor | Hans Mielke, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin - Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Kupferstichkabinett |

|---|

| Title | Albrecht Altdorfer. Zeichnungen, Deckfarbenmalerei, Druckgraphik |

|---|

| Place of Publication | Berlin |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 1988 |

|---|

|

| Schindler 1987 |

21 |

|

|

| Author | Herbert Schindler |

|---|

| Title | Sodalitas Danubia. Betrachtungen über die Donauschule und den Donaustil |

|---|

| Journal | Oberösterreiche Kulturzeitschrift |

|---|

| Issue | H. 2 |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 1987 |

|---|

| Pages | 19-29 |

|---|

|

| Exhib. Cat. Paris 1984 |

27 |

|

|

| Editor | Centre Culturel du Marais, Paris, Fedja Anzelewsky |

|---|

| Title | Altdorfer und der fantastische Realismus in der deutschen Kunst |

|---|

| Place of Publication | Paris |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 1984 |

|---|

|

| Stadlober 1982 |

151, 152 (Bd. 1) |

|

Plate XXXV (Bd. 2) |

| Author | Margit Stadlober |

|---|

| Title | Der Hochaltar der Heiligblutkirche zu Pulkau [Dissertation] |

|---|

| Volume | 1, 2 |

|---|

| Place of Publication | Graz |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 1982 |

|---|

|

| Schindler 1981 |

69 |

|

|

| Author | Herbert Schindler |

|---|

| Title | Albrecht Altdorfer und die Anfänge des Donaustils |

|---|

| Volume | 23 |

|---|

| Journal | Ostbairische Grenzmarken, Passauer Jahrbuch für Geschichte, Kunst und Volkskunde |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 1981 |

|---|

| Pages | 66-73 |

|---|

|

| Friedländer, Rosenberg 1979 |

13, 15, 66 |

No. 1 |

Fig. 1 |

| Author | Max J. Friedländer, Jakob Rosenberg |

|---|

| Editor | G. Schwartz |

|---|

| Title | Die Gemälde von Lucas Cranach |

|---|

| Place of Publication | Basel, Boston, Stuttgart |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 1979 |

|---|

|

| Klauner 1978 |

78-80 |

|

Fig. 37 |

| Author | Friederike Klauner |

|---|

| Title | Die Gemäldegalerie des Kunsthistorischen Museums. Vier Jahrhunderte europäische Malerei |

|---|

| Place of Publication | Vienna |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 1978 |

|---|

|

| Exhib. Cat. Basel 1974/1976 |

120, 124, 170, 443, 488 |

|

|

|

|

| Schade 1974 |

15, 16 |

|

Plate 1 |

|

|

| Cat. Vienna 1973 |

48 |

|

Plate 130 |

| Editor | Klaus Demus |

|---|

| Title | Verzeichnis der Gemälde |

|---|

| Series | Führer durch das Kunsthistorische Museum |

|---|

| Volume | 18 |

|---|

| Place of Publication | Vienna |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 1973 |

|---|

|

| Koepplin 1973 A |

40, fns. 101, 102 |

|

|

| Author | Dieter Koepplin |

|---|

| Title | Cranachs Ehebildnis des Johannes Cuspinian von 1502. Seine christlich-humanistische Bedeutung |

|---|

| Place of Publication | Düsseldorf |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 1973 |

|---|

| Link |

https://doi.org/10.11588/diglit.9938 |

|

| Benesch 1972 A |

5 |

|

Fig. 40 |

| Author | Otto Benesch |

|---|

| Title | Die Tafelmalerei des ersten Drittels des 16. Jahrhunderts in Österreich |

|---|

| Publication | in Eva Benesch, ed., Collected Writings of Otto Benesch. Vol. 3. German and Austrian Art of the 15th and 16th Centuries |

|---|

| Volume | 3 |

|---|

| Place of Publication | New York, London |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 1972 |

|---|

| Pages | 3-11 |

|---|

|

| Benesch 1972 B |

35-37, 42-44, 48-51 |

|

Fig. 40 |

| Author | Otto Benesch |

|---|

| Title | Zur altösterreichischen Tafelmalerei |

|---|

| Publication | in Eva Benesch, ed., Collected Writings of Otto Benesch. Vol. 3. German and Austrian Art of the 15th and 16th Centuries |

|---|

| Volume | 3 |

|---|

| Place of Publication | New York, London |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 1972 |

|---|

| Pages | 16-72 |

|---|

|

| Benesch 1972 C |

344-345 |

|

Fig. 40 |

| Author | Otto Benesch |

|---|

| Title | The Rise of Landscape in the Austrian School of Painting |

|---|

| Publication | in Eva Benesch, ed., Collected Writings of Otto Benesch. Vol. 3. German and Austrian Art of the 15th and 16th Centuries |

|---|

| Volume | 3 |

|---|

| Place of Publication | New York, London |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 1972 |

|---|

| Pages | 338-352 |

|---|

|

| Benesch 1972 D |

259-260 |

|

Fig. 40 |

| Author | Otto Benesch |

|---|

| Title | Der Zwettler Altar und die Anfänge Jörg Breus |

|---|

| Publication | in Eva Benesch, ed., Collected Writings of Otto Benesch. Vol. 3. German and Austrian Art of the 15th and 16th Centuries |

|---|

| Volume | 3 |

|---|

| Place of Publication | New York, London |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 1972 |

|---|

| Pages | 248-276 |

|---|

|

| Exhib. Cat. Vienna 1972 |

|

No. 1 |

Fig. 3 |

| Author | Karl Schütz |

|---|

| Editor | Kunsthistorisches Museum, Wien |

|---|

| Title | Lucas Cranach der Ältere und seine Werkstatt. Jubiläumsausstellung museumseigener Werke 1472-1972 |

|---|

| Place of Publication | Vienna |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 1972 |

|---|

|

| Osten, Vey 1969 |

132, 133 |

|

|

| Author | Gert von der Osten, Horst Vey |

|---|

| Title | Painting and sculpture in Germany and the Netherlands 1500 to 1600 |

|---|

| Series | Pelican History of Art |

|---|

| Volume | 31 |

|---|

| Place of Publication | Harmondsworth, Middlesex |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 1969 |

|---|

|

| Cat. Vienna 1968 |

XXI |

No. 202 |

|

| Author | n. a. |

|---|

| Title | Kunsthistorisches Museum: Meisterwerke |

|---|

| Place of Publication | Vienna |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 1968 |

|---|

|

| Talbot 1967 |

72-76 |

|

Fig. 5 |

|

|

| Benesch 1966 |

64 |

|

|

| Author | Otto Benesch |

|---|

| Title | Die deutsche Malerei. Von Dürer bis Holbein |

|---|

| Place of Publication | Geneva |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 1966 |

|---|

|

| Perger 1966 |

71, 74 |

|

|

| Author | Richard Perger |

|---|

| Title | Neue Hypothesen zur Frühzeit des Malers Lukas Cranach des Älteren |

|---|

| Journal | Wiener Geschichtsblätter |

|---|

| Issue | Jg. 21, H. 3 |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 1966 |

|---|

| Pages | 70-77 |

|---|

|

| Exhib. Cat. Linz 1965 |

|

025 |

|

| Author | Schloßmuseum Linz, Stift St. Florian |

|---|

| Editor | Otto Wutzel |

|---|

| Title | Die Kunst der Donauschule. 1490-1540 |

|---|

| Place of Publication | [Linz] |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 1965 |

|---|

|

| Stange 1964 |

52, 138 |

No. 1 |

Fig. 59 |

| Author | Alfred Stange |

|---|

| Title | Malerei der Donauschule |

|---|

| Place of Publication | Munich |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 1964 |

|---|

|

| Cat. Vienna 1963 |

35-36 |

No. 103 |

|

| Author | n. a. |

|---|

| Title | Katalog der Gemäldegalerie. 2, Vlamen, Holländer, Deutsche, Franzosen |

|---|

| Series | Führer durch das Kunsthistorische Museum |

|---|

| Volume | 8/2 |

|---|

| Place of Publication | Vienna |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 1963 |

|---|

|

| Ruhmer 1963 |

7, 85 |

|

Fig. 3 |

| Author | Eberhard Ruhmer |

|---|

| Title | Cranach |

|---|

| Place of Publication | Cologne |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 1963 |

|---|

|

| Oberhammer 1959 |

|

|

Plate 20 |

| Editor | Vinzenz Oberhammer |

|---|

| Title | Die Gemäldegalerie des Kunsthistorischen Museums. 1. Halbband: Malerei nördlich der Alpen XV. - XVII. Jahrhundert. 100 Tafeln |

|---|

| Place of Publication | Vienna, Munich |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 1959 |

|---|

|

| Exhib. Cat. Graz 1953 |

|

No. 23 |

|

| Editor | Landesmuseum Joanneum, Graz |

|---|

| Title | Dürer und seine Zeit. Meisterwerke der deutschen Malerei des 16. Jahrhunderts. Sonderausstellung der Gemäldegalerie des Kunsthistorischen Museums, Wien im Steiermärkischen Landesmuseum Joanneum, Graz [Steiermärkischen Landesmuseum Joanneum, Graz] |

|---|

| Place of Publication | Graz |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 1953 |

|---|

|

| Jahn 1953 A |

24-25, 26 |

|

Fig. 14 |

| Author | Johannes Jahn |

|---|

| Title | Der Weg des Künstlers |

|---|

| Publication | in Heinz Lüdecke, ed., Lucas Cranach d. Ä. im Spiegel seiner Zeit. Aus Urkunden, Chroniken, Briefen, Reden und Gedichten |

|---|

| Place of Publication | Berlin |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 1953 |

|---|

| Pages | 17-81 |

|---|

|

| Exhib. Cat. Oslo 1952 |

10 |

No. 36 |

|

| Editor | Nasjonalgalleriet, Oslo |

|---|

| Title | Kunstkatter fra Wien [Oslo, Nasjonalgalleriet] |

|---|

| Place of Publication | Oslo |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 1952 |

|---|

|

| Exhib. Cat. London 1949 |

|

No. 42 |

Fig. 8 |

| Editor | Tate Gallery, London |

|---|

| Title | Art treasures from Vienna [London, Tate Gallery] |

|---|

| Place of Publication | London |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 1949 |

|---|

|

| Exhib. Cat. Copenhagen 1948 |

32 |

No. 43 |

|

| Author | Statens Museum for Kunst (Denmark) |

|---|

| Title | København: Kunstkatte fra Wien. Katalog zur Ausstellung von Dez. 1948-Februar 1949 |

|---|

| Place of Publication | Copenhagen |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 1948 |

|---|

|

| Exhib. Cat. Stockholm 1948 |

62 |

No. 169 |

|

| Author | Nationalmuseum, Stockholm |

|---|

| Title | Nationalmuseum Stockholm: Konstkatter från Wien. Katalog zur Ausstellung von Mai-August 1948 |

|---|

| Series | Nationalmusei Utställningskataloger |

|---|

| Volume | 147 |

|---|

| Place of Publication | Stockholm |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 1948 |

|---|

|

| Exhib. Cat. Amsterdam 1947 |

19 |

No. 39 |

|

| Editor | Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam |

|---|

| Title | Kunstschatten uit Wenen. Meesterwerken uit Oostenrijk. Catalogus met 84 afbeeldingen. Rijksmuseum Amsterdam 10. Juli - 12. October 1947 |

|---|

| Place of Publication | Amsterdam |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 1947 |

|---|

|

| Posse 1943 |

7, 49 |

|

Pl. 1 |

| Author | Hans Posse |

|---|

| Title | Lucas Cranach d. Ä. |

|---|

| Place of Publication | Vienna |

|---|

| Issue | Second edition |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 1943 |

|---|

|

| Lilienfein 1942 |

11 |

|

Fig. 6 |

| Author | Heinrich Lilienfein |

|---|

| Title | Lukas Cranach und seine Zeit |

|---|

| Place of Publication | Bielefeld |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 1942 |

|---|

|

| Posse 1942 |

7, 49 |

|

Pl. 1 |

| Author | Hans Posse |

|---|

| Title | Lucas Cranach d. Ä. |

|---|

| Place of Publication | Vienna |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 1942 |

|---|

|

| Möhle 1940 |

117 |

|

Fig. p. 117 |

| Author | Hans Möhle |

|---|

| Title | Lukas Cranach d. Ä., Kreuzigung Christi. Um 1500 [...]. |

|---|

| Publication | in Ludwig Roselius, ed., Deutsche Kunst. Meisterwerke der Baukunst, Malerei, Bildhauerkunst, Graphik und des Kunsthandwerks |

|---|

| Volume | 6 |

|---|

| Journal | Cahiers du Musée National d'Art Moderne |

|---|

| Place of Publication | Bremen, Berlin |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 1940 |

|---|

| Pages | 117 |

|---|

|

| Exhib. Cat. Vienna 1939 |

|

No. 180 |

|

| Editor | Kaj Mühlmann, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Wien |

|---|

| Title | Altdeutsche Kunst im Donauland. Ausstellung im Staatl. Kunstgewerbemuseum |

|---|

| Place of Publication | Vienna |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 1939 |

|---|

|

| Baldass 1938 |

136 |

|

|

| Author | Ludwig Baldass |

|---|

| Title | Albrecht Altdorfers künstlerische Herkunft und Wirkung. 5. Lukas Cranach |

|---|

| Journal | Jahrbuch der Kunsthistorischen Sammlungen in Wien |

|---|

| Issue | 12 |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 1938 |

|---|

| Pages | 117-157 |

|---|

|

| Cat. Vienna 1938 |

43 |

No. 1825 |

|

| Author | n. a. |

|---|

| Title | Kunsthistorisches Museum: Katalog der Gemäldegalerie |

|---|

| Series | Führer durch das Kunsthistorische Museum |

|---|

| Volume | 8 |

|---|

| Place of Publication | Vienna |

|---|

| Issue | Second edition |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 1938 |

|---|

|

| Exhib. Cat. Munich 1938 |

|

No. 388 |

|

| Editor | Ernst Buchner, Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen |

|---|

| Title | Albrecht Altdorfer und sein Kreis Gedächtnis-Ausstellung zum 400. Todesjahr Altdorfers |

|---|

| Place of Publication | Munich |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 1938 |

|---|

|

| Wolters 1938 |

120, 121 |

|

Figs. 68, 70 |

| Author | Christian Wolters |

|---|

| Title | Die Bedeutung der Gemäldedurchleuchtung mit Röntgenstrahlen für die Kunstgeschichte. Dargestellt an Beispielen aus der niederländischen und deutschen Malerei des 15. und 16. Jahrhunderts |

|---|

| Series | Veröffentlichungen zur Kunstgeschichte |

|---|

| Volume | 3 |

|---|

| Place of Publication | Frankfurt am Main |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 1938 |

|---|

|

| Exhib. Cat. Berlin 1937 |

13 |

001 |

Pl. 5 |

| Editor | Staatliche Museen, Berlin |

|---|

| Title | Lucas Cranach d. Ä. und Lucas Cranach d. J. Gemälde, Zeichnungen, Graphik |

|---|

| Place of Publication | Berlin |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 1937 |

|---|

|

| Burke 1936 |

32 |

|

|

| Author | W. L. M. Burke |

|---|

| Title | Lucas Cranach the Elder |

|---|

| Journal | The Art Bulletin |

|---|

| Issue | 18/1 |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 1936 |

|---|

| Pages | 25-53 |

|---|

|

| Leporini 1935 A |

45 |

|

|

| Author | Heinrich Leporini |

|---|

| Title | Rundschau, Museen |

|---|

| Journal | Pantheon |

|---|

| Issue | Jg. 15, H. Jan.-Juni |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 1935 |

|---|

| Pages | 45 |

|---|

|

| P. 1935 |

3 |

|

|

| Author | N. P. |

|---|

| Title | L. Cranachs Wiener Jahre |

|---|

| Journal | Weltkunst: Zeitschrift für Kunst und Antiquitäten |

|---|

| Issue | Jg. IX, Nr. 14, 7. April 1935 |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 1935 |

|---|

| Pages | 3 |

|---|

|

| P. 1934 B |

10 |

|

with Fig. |

| Author | N. P. |

|---|

| Title | Cranach-Kauf des Wiener Museums |

|---|

| Journal | Weltkunst: Zeitschrift für Kunst und Antiquitäten |

|---|

| Issue | Jg. VIII, Nr. 49, 9. Dezember 1934 |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 1934 |

|---|

| Pages | 10 |

|---|

|

| Friedländer, Rosenberg 1932 |

3, 7 |

1 |

|

|

|

| Buschbeck 1931 A |

43 |

|

Fig. 3 |

| Author | Ernst Buschbeck |

|---|

| Title | Führer durch die Gemäldegalerie. Mit. 165 Abbildungen |

|---|

| Series | Führer durch die Kunsthistorischen Sammlungen in Wien |

|---|

| Volume | 3 |

|---|

| Place of Publication | Vienna |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 1931 |

|---|

|

| Baldass 1928 |

76, 77, 80 |

|

|

| Author | Ludwig Baldass |

|---|

| Title | Cranachs Büssender Hieronymus von 1502 |

|---|

| Journal | Jahrbuch der Preußischen Kunstsammlungen |

|---|

| Issue | 49 |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 1928 |

|---|

| Pages | 76-81 |

|---|

|

| Benesch 1928 A |

92-93, 94, 101 |

|

Fig. 138 |

| Author | Otto Benesch |

|---|

| Title | Zur Altösterreichischen Tafelmalerei. I. Der Meister der Linzer Kreuzigung, II. Die Anfänge Lukas Cranachs |

|---|

| Journal | Jahrbuch der Kunsthistorischen Sammlungen in Wien |

|---|

| Issue | Sonderheft N. S. 13 |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 1928 |

|---|

| Pages | 63-118 |

|---|

|

| Benesch 1928 C |

|

|

|

| Author | Otto Benesch |

|---|

| Title | Der Zwettler Altar und die Anfänge Jörg Breus. Beiträge zur Geschichte der Deutschen Kunst |

|---|

| Publication | in Ernst Buchner and Karl Feuchtmayr, ed., Augsburger Kunst der Spätgotik und Renaissance |

|---|

| Place of Publication | Augsburg |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 1928 |

|---|

| Pages | 229-271 |

|---|

|

| Glaser 1923 |

18-24 |

|

Fig. p. 19 |

|

|

| Ankwicz Kleehoven 1922 |

59-60 |

|

|

| Author | Hans Ankwicz Kleehoven |

|---|

| Title | Lucas Cranach in Wien |

|---|

| Journal | Altwiener Kalender |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 1922 |

|---|

| Pages | 58-65 |

|---|

|

| Baldass 1922 B |

80 |

|

|

| Author | Ludwig Baldass |

|---|

| Title | Die altösterreichischen Tafelbilder der Wiener Gemäldegalerie |

|---|

| Journal | Wiener Jahrbuch für bildende Kunst |

|---|

| Issue | Jg. 5 |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 1922 |

|---|

| Pages | 67-86 |

|---|

|

| Frimmel 1917 |

104-105 |

|

|

| Author | Theodor von Frimmel |

|---|

| Title | Die Gemäldesammlung des Wiener Schottenstiftes |

|---|

| Journal | Studien und Skizzen zur Gemäldekunde |

|---|

| Issue | Jg. III. Band, H. I. und II. Lieferung (Jänner 1917) |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 1917 |

|---|

| Pages | 101-108 |

|---|

|

| Fischer 1907 |

71 |

|

|

| Author | Otto Fischer |

|---|

| Title | Rezension von: Hermann Voss, Der Ursprung des Donaustils, Leipzig 1907 |

|---|

| Journal | Kunstgeschichtliche Anzeigen |

|---|

| Issue | Jg. 4, H. 2-4 |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 1907 |

|---|

| Pages | 66-76 |

|---|

|

| Riggenbach 1907 |

25 |

|

|

| Author | Rudolf Riggenbach |

|---|

| Title | Der Maler und Zeichner Wolfgang Huber |

|---|

| Place of Publication | Basel |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 1907 |

|---|

|

| Voss H. 1907 |

97 |

|

|

| Author | Hermann Voss |

|---|

| Title | Der Ursprung des Donaustiles. Ein Entwicklungsgeschichte deutscher Malerei |

|---|

| Place of Publication | Leipzig |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 1907 |

|---|

|

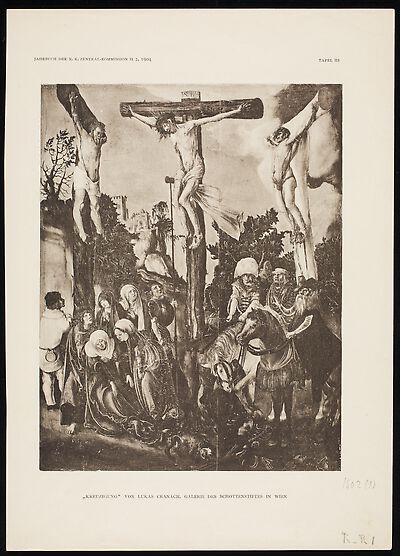

| Dörnhöffer 1904 |

175-198 |

|

|

| Author | Friedrich Dornhöffer |

|---|

| Title | Ein Jugendwerk Lukas Cranachs |

|---|

| Journal | Jahrbuch der k.k. Zentralkommission für Kunstdenkmale Wien |

|---|

| Issue | N. F., II, 2 |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 1904 |

|---|

| Pages | 175-198 |

|---|

|

| Frimmel 1896 B |

4 |

|

|

| Author | Theodor von Frimmel |

|---|

| Title | Ein Gang durch die Galerie des Schottenstiftes zu Wien. I. Feuilleton |

|---|

| Journal | Wiener Zeitung |

|---|

| Place of Publication | Vienna |

|---|

| Issue | Jg. 1896, 6.2.1896 |

|---|

| Year of Publication | 1896 |

|---|

| Pages | 3-5 |

|---|

|