- Attributions

-

Lucas Cranach the Younger

Lucas Cranach the Younger (?)

Attributions

| Lucas Cranach the Younger | [Schulze 2004, 203-204] [Schade 1974] [Kehrer 1916] |

| Lucas Cranach the Younger (?) | [http://predigerseminar-cdm.gbv.de/u?/Gemaelde,87; 11.07.2012] |

- Production date

- 1571

Production date

| 1571 | dated |

- Dimensions

- Dimensions of support: 250 x 156 cm

Dimensions

Dimensions of support: 250 x 156 cm

[Wimböck 2010, 171] [Lutherhaus Wittenberg, revised 2012]

247 cm x 157 cm

[Schade 1974, 390]

248 cm x 155 cm

[Bellmann, Harksen, Werner 1979, 72]

251.5 cm 161 cm (with additions)

[Körber 1981]

251 cm x 158 cm

Dimensions including frame: 272 cm x 180.5 cm

[Treu 2003, 105]

- Signature / Dating

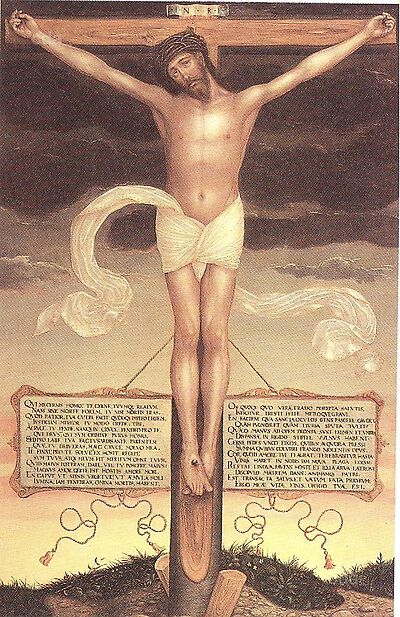

Artist's insignia below the feet of Christ: winged serpent, facing right with elevated wings and dated '1571'

Signature / Dating

Artist's insignia below the feet of Christ: winged serpent, facing right with elevated wings and dated '1571'

[Görres, CDA 2012]

- Inscriptions and Labels

- On both sides of the cross.

Left: 'QVI ME CERNIS HOMO: TE CERNE, TVVMQ REATVM,

NAM SINE MORTE FOREM, …Inscriptions and Labels

Inscriptions, Badges:

- On both sides of the cross.

Left:

'QVI ME CERNIS HOMO: TE CERNE, TVVMQ REATVM,

NAM SINE MORTE FOREM, TV NISI MORTIS ERAS.

QVOD PATIOR, TVA CVLPA FACIT QVODQ IMPLEO LEGEM,

IVSTICIAM MEREOR TV MODO CREDE, TIBI.

A CRVCE TV PENDE, NANQ IN CRVCE PENDEO PRO TE.

QVI DEVS, ET QVI SVM CRIMINE PVRVS HOMO.

SED PRO LABE TVA FACTVS VADIS ANTE PARENTEM

QVAE TV DEBVERAS, HAEC CRVCE SOLVO MEA.

TE FINXI: PRO TE SOLVI: TE EX HOSTE RECEPI:

SVM TVVS, ATQ MEVM FIT MERITVM OMNE TVVM.

QVID MAIVS POTERAM, DARE VEL TV POSCERE MAIVS?

MAGNVS AMOR CERTE EST HOSTIS AMORE MORI.

EN CAPVT, VT SPINIS VRGETVR? VT AEMVLA SOLI

LVMINA, IAM TENEBRAS, OMNIA MORTIS, HABENT.'

Right:

'OS QVOQ QVO VERAE TRADO PRAECEPTA SALVTIS,

INFICITVR TRISTI FELLE, MEROQVE GRAVI.

EN FACIEM QVA SANCTA OCVLOS GENS PASCERE GAVDET,

QVAM PVGNOS, ET QVAM LIVIDIA SPVTA TVLIT?

QVAEQ MANVS AD OPEM PROMTAE ,SVNT TEGMEN ET VMBRA,

DISPANSAE IN RIGIDO STIPITE VVLNVS HABENT.

CERNE PEDES VNGO FIXOS, QVIBVS AEQVORA PRESSI

SVMMA: QVIBVS COLVBRI FRANGO NOCENTIS OPVS.

COR, QVOD AMORE TVI FIAGRAT, TEREBRABITVR HASTA:

VIXQ HABET IN NOBIS IAM NOVA PLAGA LOCVM.

RESTAT LINGVA, FAVENS HOSTI ET LOETA ARVA LATRONI

DISCIPVLO MATREM DANS: ANIMAMQ PATRI.

EST TRANSACTA SALVS, ET VATVM FATA PRIORVM;

ERGO MEAE VITAE FINIS, ORIGO TVAE EST.'

[Major, Johannes: Eligiae

Eligiae à Johan: Maiore D. conscriptae: Deo, et virtuti, o. O. 1584, B 4r und B 5v: Elegia De Christo, In Agone constituto.]

- Owner

- Evangelisches Predigerseminar Wittenberg

- Repository

- Lutherhaus Wittenberg

- Location

- Wittenberg

- CDA ID

- DE_EPSW_05

- FR (1978) Nr.

- FR-none

- Persistent Link

- https://lucascranach.org/en/DE_EPSW_05/

- On both sides of the cross.

Provenance

- according to Gottfried Suevus it belonged to the Augustine Convent [Suevus [1655]]

- allegedly in the university collection [Bellmann, Harksen, Werner 1979, 72]

- archive of the Protestant Seminary (Evangelischen Predigerseminar) Wittenberg, Akte 64, obtained in 1835, inventory of paintings in the Lutherhaus, Wittenberg, Folio 48r.

[Désirée Monsees, April 2012]

Literature

| Reference on page | Catalogue Number | Figure / Plate | |||||||||||||||

| Rhein 2015 | 48, Fn. 41 | ||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

| Sitt, Monsees 2015 | 310-313, 316 | Figs. 2, 3 | |||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

| Werner 2015 | 15 | ||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

| Wimböck 2010 | 171-178 | 2 | |||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

| Schulze 2004 | 203-206 | p. 204 | |||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

| Laube 2003 | 149-150, 154 | 47 | |||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

| Treu 2003 | 20 | 8 | |||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

| Cat. Wittenberg 1993 | 61-62 | 48 | |||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

| Exhib. Cat. Wittenberg 1992 | 61, 62 | ||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

| Treu, Pellmann 1991 | 41 | ||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

| Koepplin 1988 | 184-185 | 24 | |||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

| Exhib. Cat. Wittenberg 1984 | 36, 37, 41 | pl. 7 | |||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

| Kabus, Pötschke 1983 | 4, 10 | ||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

| Bellmann, Harksen, Werner 1979 | 47 | 47 | |||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

| Schade 1974 | 95, en.691 | p. 432 d | |||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

| Thulin 1967 | 54-55 | 46 | |||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

| Thulin 1956 | 54-55 | 45 | |||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

| Jordan 1924 | 11, 12, 27, 60 | ||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

| Jordan 1920 | 16 | ||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

| Kehrer 1916 | 168-169 | 9 | |||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

| Suevus 1655 | |||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

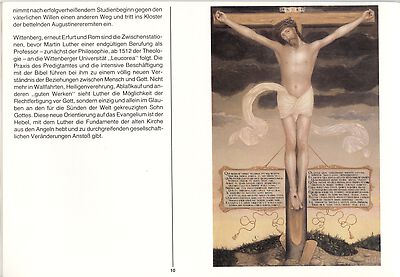

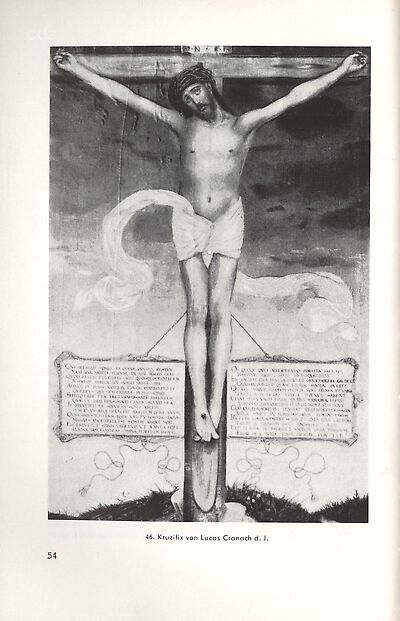

Research History / Discussion

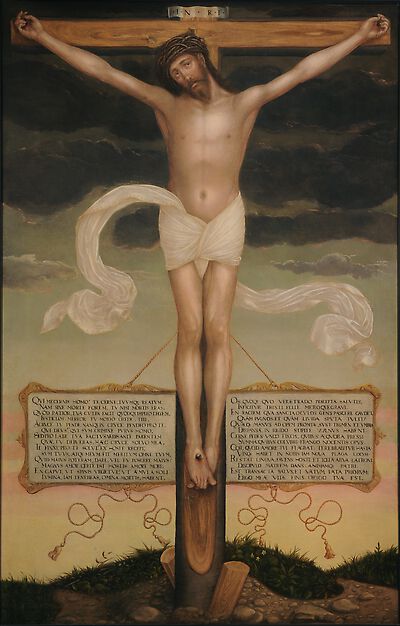

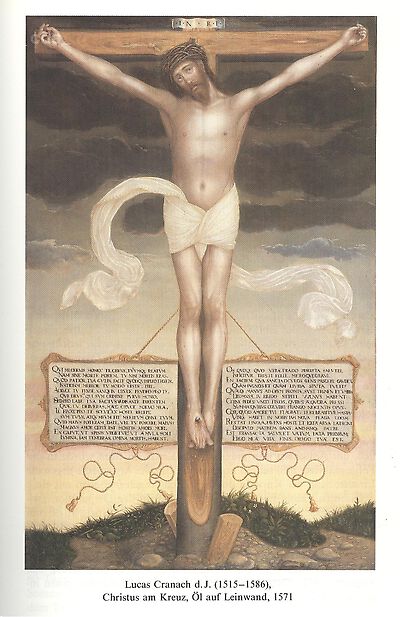

The painting depicts Christ still alive on the cross. Dark clouds serve as a backdrop in the upper half and in the bottom third there is a Latin inscription in capitals on a plaque, which is attached to the horizontal beam with a cord. Towards the horizon the background begins to clear turning from a pale bluish-green to a pale yellow interspersed with pink stripes along the transition. The scene is located on a narrow, hilly strip of land painted with great attention to detail. Little is known about when and who commissioned the large format painting, its original function or its provenance. Allegedly it was in the university collection and belonged to the Augustine Convent.[1]

The large format painting on canvas is not the first depiction of the solitary crucified Christ as was assumed by Kehrer (1916) in his discussion of the Dresden Crucifixion with the Dürer monogram.[2] On the contrary it recalls the pictorial type shown on the painting by Lucas Cranach the Younger from 1540 now in Dublin. However in contrast to this the depiction in Wittenberg concentrates on Christ without further elaboration and narrative in the background landscape. In addition the figure of Christ looks at the viewer with his head slightly inclined.

According to Schade the pictorial type of the living Christ on the cross, without the wound in his side and looking upwards appears in the work of Lucas Cranach the Younger from 1536. Schade considers the small format Crucifixion in Dresden, which he attributes to Dürer and dates 1500, to be the source of inspiration for this pictorial type.[3] This dependency has already been disputed, and recent research is of the opinion, that the panel in Dresden is a forgery, an improved copy of Cranach’s painting in Dublin and that this pictorial type was coined by Cranach. [4] According to Schade the large format painting was together with the depictions of Christ on the Cross with Donors on an Epitaph from 1570 in Nienburg and 1571 in Augustusburg an exception in the late phase where otherwise small scale figures predominated. The depiction of the Crucifixion was one of the main subjects in the younger Cranach’s late works. [5]

Art historical research agrees that this painting illustrates a fundamental principle of the reformist Passion theology. Martin Luther interpreted the cross of Christ as a form of comfort giving strength and assistance and not only terrifyingly recalling the gesture of divine judgment. For him the crucifixion was the most emphatic visualization that only faith in God can redeem the sinner and it corresponded most closely with his expectations of Christian iconography: it presents the grace of God through Christ to the faithful viewer and keeps their faith alive. It can assist the faithful in prayer, particularly if an inscription gives the painting its correct meaning.[6] Within his study of the comforting aspect of the crucifixion Koepplin interprets the Wittenberg Crucifixion in accordance with Luther’s understanding. He states that the mercy and love of God towards mankind are conveyed in the crucifixion as a merciful ‘surrender’ (Zusich-Ziehen), without fear the faithful can confront his own sins, which Christ has taken away from him. The depiction in Wittenberg units as such the old, pre-reformist understanding, which is given expression in the phrase: ‚Tua culpa facit‘ in the inscription with the comforting aspect promoted by Luther. Christ includes the viewer in his prayer and invites him to pray.[7] Koepplin interprets the Crucifixion as ‚at once symbolic, bound to the text and made accessible through a mellowed realism, which is fundamentally different from the realism and the power of medieval Crucifixions.‘[8] Schulze interprets the painting according to Melanchton and his pupils, who consider this image from the Passion to be particularly apt for meditation, because it both comforts and admonishes. Schulze detects a similarity with prayers by Melanchton in the first part of the inscription and sees an analogy with medieval mysticism in the detailed description of Christ’s suffering and in the concentration on each wound, in particular the depiction of the Man of Sorrows.[9] She ascribes the visualization of the Christ’s sacrificial death as a place of rehabilitation and the emphasis on pity and compassion in this depiction to a characteristic trait of Lucas Cranach the Younger. She attests the painter’s sensitizing process, which leads to an intense feeling of devotion towards Christ.[10] For Wimböck this appeal for immersion recalls a text in the passion, in which the events of the passion are invoked in a similar manner to that employed in the late Middle Ages rather than the Reformation. However, she refers to examples in a protestant context in which ‚the sufferings are counted‘.[11]

Studies of the painting often view it in correlation with the pictorial type of the prominent converted centurion, but also associate it with the medieval images of the sacred-heart.[12] Schulze associates the Wittenberg Crucifixion with medieval depictions of the sacred heart of Jesus like they were dealt with in a pre-reformation woodcut by Lucas Cranach the Elder 1505.[13] Koepplin ascertains that this woodcut does not by chance recall the Luther-Rose. However he does differentiate between two strands: the Late Middle Age image of the sacred heart and reformist image, the latter is accentuated in accordance with Luther’s understanding of God’s love and compassion to mankind and is generally different.[14]

Wimböck has to date written the most extensive interpretation of the painting and has focused in particular on the relationship of the figurative depiction and the inscription. She interprets the inscription as a continuation of the inferred invocation of the viewer through the direct eye contact with Christ. Wimböck emphasizes that the text has an image-like and independent status, whereby the combination of word and image encourages extensive contemplation. This thesis is supported by the fact that the size, position and decorative elements of the text prove it to be equal to the visual depiction and together with the visual image allows a meditative appreciation – as Luther wished. In connection with her thoughts on the ‘narrative’ texts recalling the events of the Passion Wimböck interprets the work as an allocutive visual poem, which she sets in a humanist-reformist context. She interprets the prominent, radiant and almost immaculate figure of Christ as a void for reflection on the Passion and the cord beneath the plaque as an aid to the imagination for the viewer.[15]

The inscription does not by chance recall prayers by Melanchton and as stated by Wimböck is found verbatim in the volume of poems entitled ‚Elegiae‘[16] by Johann Maior, a pupil of Melanchthon and Professor of Poetics in Wittenberg. Within the context of the inner reformist conflict between the Philippists and orthodox Lutherism from the 1750s, which finally became a theological controversy and doctrinal dispute, the intervention by Elector August in 1574 can be seen to have lead to the fall of Philippism in Saxony. As a self-confessed Philippist Johann Maior was also affected by the persecution of the so-called Cryptocalventists.[17] Wimböck concludes from this that together with the stylistic evidence the painting must have been created before the unrest in 1574. She includes another cooperative work between Cranach the Younger and Johann Maior: the poet supposedly wrote the text for the inscriptions on the Epitaphs in the castle church (Schlosskirche) of Augustusburg. Schulze attributes them to his father Georg Maior, Professor of Theology in Wittenberg, but Wimböck assumes here that past research is responsible for a generally incorrect designation.[18]

[Désirée Monsees, Martina Sitt, April 2012]

[1] Suevus, Gottfried: Academia Wittebergensis ab anno fundationis 1502 festo divae Lucae die XIIX. mens. Octobr. usque ad annum 1655 ..., Wittenbergae [1655] und Bellmann, Fritz; Harksen, Marie-Luise; Werner, Roland (Bearb.): Die Denkmale der Lutherstadt Wittenberg, Weimar 1979, 72.

[2] Kehrer, Hugo: Über die Echtheit von Dürers Crucifixus, in: Zeitschrift für bildende Kunst, NF 27 (1916), 163-172.

[3] Schade, Werner: Die Malerfamilie Cranach, Dresden 1974, 86-87.

[4] Kroll Renate: E 62 Christus am Kreuz, in: Schade, Günter: Kunst der Reformationszeit. Ausstellung im Alten Museum vom 26. August - 13. November 1983, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Hauptstadt der DDR, Ausst.-Katalog, Berlin: Elefanten-Press-Verl. 1983 or Flügel, Katharina (revised): Kunst der Reformationszeit. Ausstellung im Alten Museum vom 26. August - 13. November 1983, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Hauptstadt der DDR, Ausst.-Katalog, Berlin: Henschel 1983, 367.

[5] Schade 1974, 95-96.

[6] Stirm, Margarete: Die Bilderfrage in der Reformation, Gütersloh 1977 (and: Berlin, Kirchl. Hochschule, Diss., 1973 with the title: Stirm, Margarete: Die Bilderfrage bei den Reformatoren), 79-80; 87-89; 113 and D. Martin Luthers Werke. Kritische Gesamtausgabe, ed. J. F. Knaake [et al], 61 Bd., Weimar 1883-1983, Bd. 2, 131-143; Bd. 48, 194-200.

[7] Koepplin, Dieter: Kommet her zu mir alle. Das tröstliche Bild des Gekreuzigten nach dem Verständnis Luthers, in: Löcher, Kurt (ed.): Martin Luther und die Reformation in Deutschland. Vorträge zur Ausstellung im Germanischen Nationalmuseum Nürnberg 1983, Heidelberg [1988] (Schriften des Vereins für Reformationsgeschichte, Bd. 194), 183-185.

[8] Koepplin 1988, 185.

[9] See: Schulze, Ingrid: Lucas Cranach d. J. und die protestantische Bildkunst in Sachsen und Thüringen. Frömmigkeit, Theologie, Fürstenreformation, Bucha bei Jena 2004 (Reihe Palmbaum Texte. Kulturgeschichte, Bd. 13), 203-204.

[10] See: Schulze 2004, 203-206.

[11] Wimböck, Gabriele: Wort für Wort, Punkt für Punkt. Darstellungen der Kreuzigung im 16. Jahrhundert in Deutschland; in: Steiger, Johann Anselm; Heinen, Ulrich (ed.): Golgatha in den Konfessionen und Medien der Frühen Neuzeit, Berlin [et al]: 2010, 172.

[12] Koepplin; Falk 1976, Bd. 2, 470.

[13] Schulze 2004, 206.

[14] Koepplin 1988, 166-171.

[15] Wimböck 2010, 174.

[16] Eligiae à Johan: Maiore D. conscriptae: Deo, et virtuti, o. O. 1584, B 4r und B 5v: Elegia De Christo, In Agone constituto.

[17] See: Tschackert, Paul: „Major, Johann“, in: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie 20 (1884), 111 and Ludwig, Ulrike: Philippismus und orthodoxes Luthertum an der Universität Wittenberg. Die Rolle Jakob Andreäs im lutherischen Konfessionalisierungsprozeß Kursachsens (1576-1580), Münster: Aschendorff 2009 (Reformationsgeschichtliche Studien und Texte Bd. 153), 55-59, 78-125, 221-222.

[18] Schulze 2004, 211; Wimböck 2010, 176.