Portrait of Martin Luther on his Death-bed

Since the proclamation of his 95 theses in 1517, the Leipzig disputation in 1519 and the publication of three reformation manifestos Martin Luther has become both a well known and controversial figure in Germany and beyond. Interest arose in his views, and also in his character, his personal circumstances and his appearance. Lucas Cranach the Elder and his workshop satisfied the desire for representations of Luther. He created portraits employing a variety of techniques: engravings, woodcuts and a number of oil paintings, which were repeated employing an innovative method of serial production. It was thanks to Cranach that Luther became one of the most frequently portrayed men of his time. The motivation came from the political intent of the Saxon electors and the business sense of the artist, who was personally closely linked to Luther. The image of the Reformer was disseminated, simplified, idealized or negatively distorted through copies by other artists.[1]

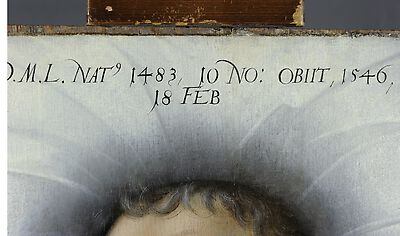

In Cranach’s portraits Luther is shown as a forceful and unfaltering monk, as a scholar with a mortar board, as ‚Junker Jörg‘ with a beard, as a husband with his wife Katharina of Bora and - together with Melanchton – as an unwavering confessor and theological authority, as a church father of the strengthening protestant confession. The image of the deceased is also part of the Luther iconography: the reformer died at the age of 62 on the morning of the 18th of February 1546 in Eisleben, where he had gone to settle the inheritance dispute between the two Mansfeld counts Gebhard and Albrecht. Literary sources record that he was portrayed by both a local artist and the artist Lucas Furtenagel, who was quickly brought from Halle.[2] It may be assumed that one of the brush drawings depicting the deceased, now in Berlin and probably that by Furtenagel, was acquired by Lucas Cranach in Wittenberg. On the basis of this he created the painting in the Niedersächsischen Landesmuseum Hannover, which became a prototype for numerous copies. [3] Copies were made as if from an icon and in turn these were copied. The version from Karlsruhe shown in the exhibition belongs to a number of the fourteen known versions, which are not from the Cranach workshop and it is probably not even contemporary. [4] Comparison with the version in Hannover shows that the lower arms and hands are omitted, but that the rendition of face of the deceased is very accurate. It is determined by a mild, peaceful expression. This was important, because opposers of the Reformation had prophesied an agonising death for the heretic, who was supposedly allied with the devil. In their eyewitness account of Luther’s death, which was published in great hast, Justus Jonas and Michael Coelius emphasize: „Und kond niemands mercken (das zeugen wir fur Gott auff unser gewissen) einige unruge, quelung des leibes oder schmertzen des todes, sondern entschlieff friedlich und sanfft im Herrn, wie Simeon singet.“ (and nobody could notice (this we swear so help us God) any restless, swelling of the body or the pain of death, but rather he passed away peacefully and softy with God, as sung by Simeon [5] Cranach’s painting and the subsequent copies are the pictorial confirmation. The white, finely pleated shirt, in which the deceased was clothed, serves to underline the impression of a clear conscience.

Holger Jacob-Friesen

[1] see Martin Warnke: Cranachs Luther. Entwürfe für ein Image, Frankfurt a. M. 1984.

[2] for the context see: Alfred Dieck: Cranachs Gemälde des toten Luther in Hannover und das Problem der Luther-Totenbilder, in: Niederdeutsche Beiträge zur Kunstgeschichte Bd. 2 (1962), 191-218.

[3] Exhib. Cat. Cranach der Ältere, Frankfurt a. M. 2007, no. 42. The catalogue entry contests quite correctly the asumption made by Dieck, that only the painting recorded in literary sources by the artist from Eisleben served as a prototype for Cranach.

[4] Dieck dates the painting – however not very convincingly – very late, namely during the ‚Enlightenment‘ (18th century): Dieck 1962 (as Fn. 2), 202.

[5] Justus Jonas und Michael Coelius: Bericht vom christlichen Abschied aus diesem tödlichen Leben des ehrwürdigen Herrn D. Martini Lutheri (publ. in Wittenberg, March 1546), cited: D. Martin Luthers Werke. Kritische Gesamtausgabe, vol. 54, Weimar 1928, p. 492.