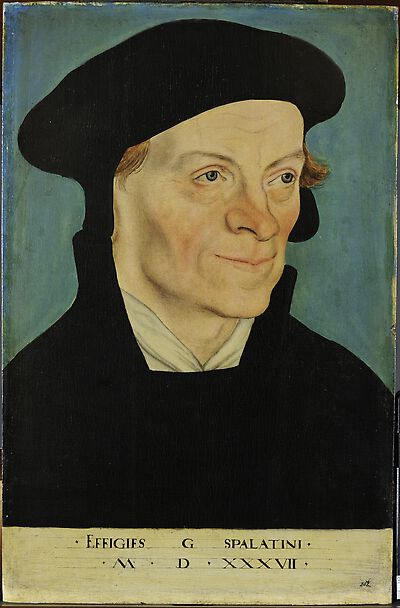

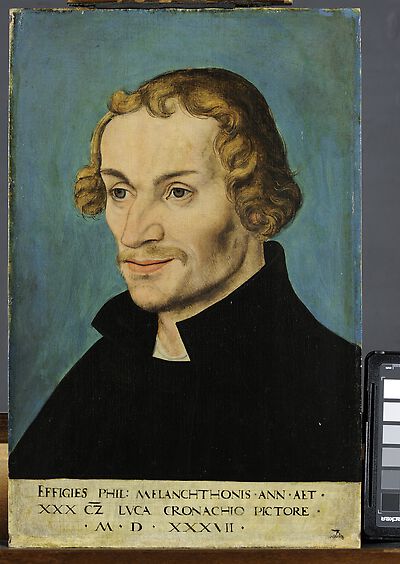

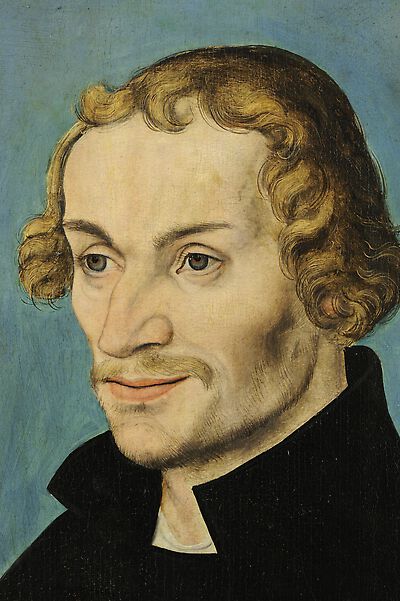

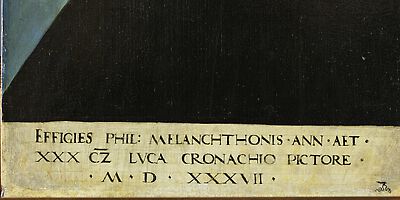

Portrait of Georg Spalatin / Portrait of Philipp Melanchthon

About 1530 the hopes of many Lutherans to establish a fundamental consensus with the Swiss Reformists on the one hand and the members of the ‚Old Church’ on the other were disappointed. In 1529 the Religious Colloquy in Marburg between Luther and Zwingli failed, in 1530 the Catholics under Emperor Charles V rejected the ‚Confessio Augustana‘, which had been conceived by Philipp Melanchthon in a conciliatory tone and had been presented by him personally in the Augsburg Reichstag. It thus became a matter of course that Lutheranism developed an independent Church. During this period Lucas Cranach painted portraits of Martin Luther’s intimate friends and colleagues. A third portrait appears to belong with the portraits shown here of Georg Spalatin and Philipp Melanchthon. The portrait of Johannes Bugenhagen, now in the Lutherhalle Wittenberg follows the same concept and is of the same size and date. [1] It is unknown whether Cranach created the works on commission, possible by a prince, as both paintings from Karlsruhe boast a princely provenance extending back to the 17th century.[2] It is also unknown whether or not further portraits belonged to the series. One may wish, at least in thought, to add the portrait of Luther.

Georg Spalatin (1484-1545) became Friedrich the Wise’s privy secretary and confessor after his law studies and ordination. He advised the elector in profane and spiritual matters. Above all he ensured that he held a protective hand over Luther, with whom Spalatin had been friends since 1515. After Friedrich’s death Spalatin became pastor in Altenburg, but he remained an important advisor to the electors. He had a long-term relationship of trust with Johann Friedrich, who came to power in 1532 and whom he had taught as a young prince. In close collaboration with Luther he re-organised the Saxon church according to Lutheran doctrine. In 1537, the year the Cranach portrait was executed, he accompanied Luther to the Schmalkalden Bundestag for Protestant States and cities. At the same time the reformation was introduced in Denmark. Here another close friend of Luther the theologist Johannes Bugenhagen (1485-1558) from Wittenberg played a decisive role.

Philipp Melanchthon (1497-1560) was alongside Luther an important representative and co-founder of the new doctrine. Already publically praised by Erasmus for his erudition at the age of 18 he then became Professor of Greek at the University of Wittenberg when he was 21. His life’s work was the synthesis of Humanism and Reformation. The significant contribution he made to improve the universities and the education system helped Protestantism to attain a scholarly basis and to become an effective educational movement.

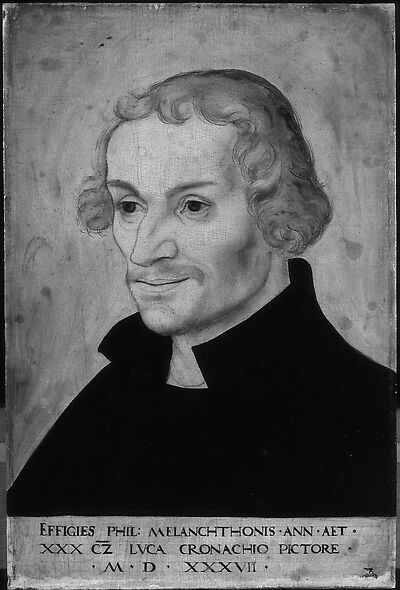

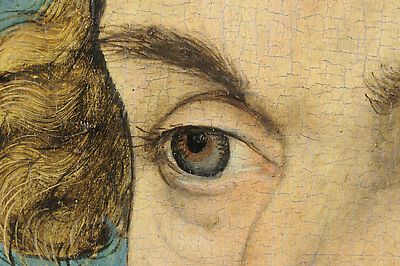

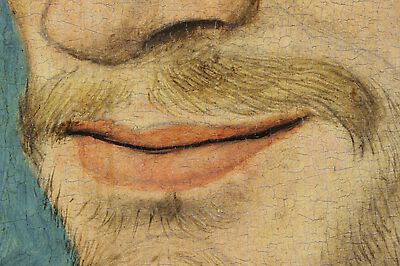

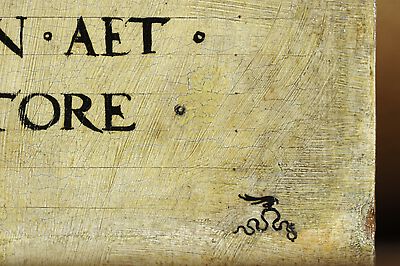

The portraits of Spalatin and Bugenhagen were probably painted by Cranach in 1537 from life or after a life-drawing; other versions of these paintings are not known. On the contrary in the case of Melanchthon he recoarsed to an older prototype, a portrait from 1532. There are more versions of this painting, usually combined with a portrait of Luther. [3] The version in Dresden bares the age 30, which was evidently adopted for the painting in Karlsruhe. In both cases it is misleading, because Melanchthon was 35 in 1532, and therefore 40 years of age in 1537. The inscription LVCA CRONACHIO PICTORE probably refers to Cranach the Elder, the head of the workshop. His son, who has the same name and was then 21 may have assisted in the execution.[4] The paint is applied very thinly. The infrared reflectogram reveals the vibrant underdrawing.[5]

The association of an image with a Latin text in capitals is a feature of Humanist portraits. Nothing indicates that the sitters portrayed here are Reformers. It was only later that Lucas Cranach the Younger and others developed the Reformer type portrait: large in format, with the Holy Scripture in a prominent position and the sitter increasingly monumental and inaccessible.[6] Both paintings from Karlsruhe evidently belong to an earlier period: Spalatin and Melanchthon are depicted without attributes and without an authoritative tone. They appear – despite their self-confidence- modest and authentic.

Holger Jacob-Friesen

[1] Max J. Friedländer/Jakob Rosenberg: Die Gemälde von Lucas Cranach, Basel, Boston, Stuttgart 1979, No. 351.

[2] They were probably in the collection of the Dukes of Saxony-Lauenburg and entered the collection of the Margrave of Baden-Baden after the marriage of Princess Sibylla Augusta to Ludwig Wilhelm of Baden in 1691. The Baden-Saxon-Lauenburg allied coat-of-arms is stamped in red sealing wax on the reverse of the portrait of Melanchthon.

[3] Friedländer/Rosenberg 1979 (as Fn. 1), No. 314-315 as well as the versions A-C; see also: Sibylle Harksen: Bildnisse Philipp Melanchthons, in: Philipp Melanchthon. Humanist, Reformator, Praeceptor Germaniae, hrsg. vom Melanchthon-Komitee der Deutschen Demokratischen Republik, Berlin 1963, 270-287.

[4] for an attribution to Lucas Cranach the Younger see: Friedländer/Rosenberg 1979 (as Fn. 1), 140; Irmgard Höß: Georg Spalatin 1484-1545. Ein Leben in der Zeit des Humanismus und der Reformation, Weimar 1989, XXXVII.

[5] Photographs in the Archiv der Staatlichen Kunsthalle Karlsruhe. Results of dendrochronologial examination of the beech wood panel carried out by Peter Klein in 1981 confirm the date 1537.

[6] see: Kurt Löcher: Humanistenbildnisse – Reformatorenbildnisse. Unterschiede und Gemeinsamkeiten, in: Hartmut Boockmann u. a. (Hrsg.): Literatur, Musik und Kunst im Übergang vom Mittelalter zur Neuzeit (Abhandlungen der Akademie der Wissenschaften in Göttingen, Phil.-Hist. Klasse, 3. Folge, No. 208), Göttingen 1995, 352-390.

![Johann the Steadfast, Elector of Saxony [central panel of the triptych]](https://lucascranach.org/imageserver-2022/DE_HKH_HK-606b_FR338/01_Overall/DE_HKH_HK-606b_FR338_2012-08_Overall-s.jpg)