English summary of the article by Hanna Benesz, in „Art&Business”, no. 12/2012 (263), pp. 120-123.

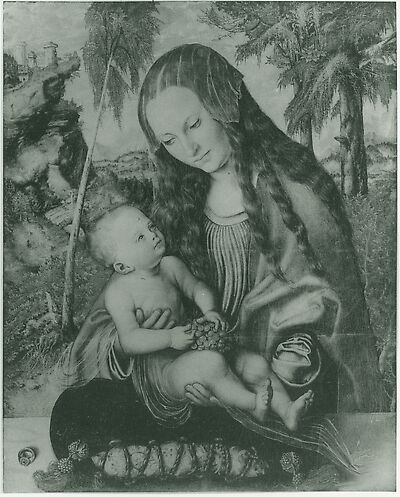

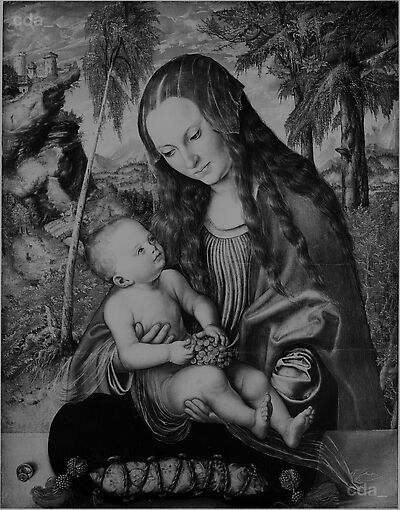

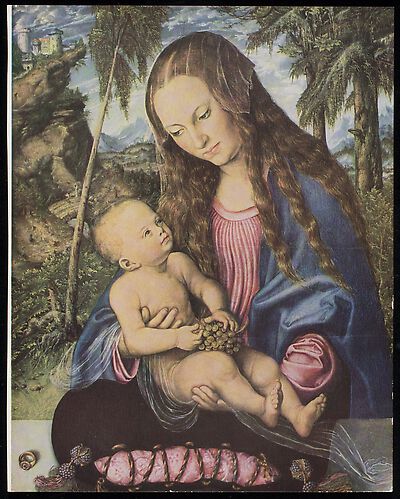

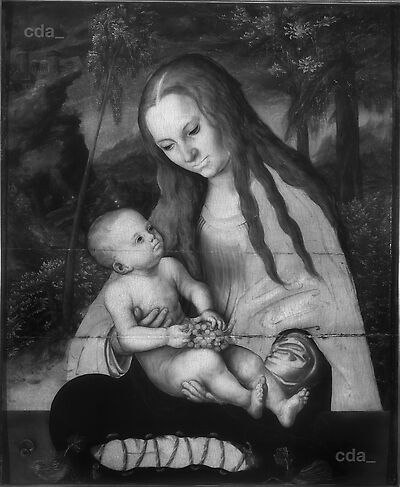

Miraculously recovered: Kidnapped just after the war, wrapped in oilcloth disappeared for 65 years. Today she returns triumphantly, almost like a movie star. This is a story about the Virgin and Child under Fir Trees, one of the most beautiful Lucas Cranach’s paintings.

A story, first published in the daily newspaper “Gazeta Wyborcza” on July 28th 2012 by Wlodzimierz Kalicki of the painting’s disappearing is summed up here:

The chapter 400 years of peace reminds the history of the commission of the painting by one of the Wroclaw cathedral’s canons around 1510 directly at Cranach’s Wittenberg workshop. The painting stayed in the cathedral for 400 years until it was evacuated for safety in 1943. It did return already in 1945, but damaged (split into two parts). The new Church authorities engaged the pre-war employee of the Archbishopric Museum, reverend Siegfried Zimmer to manage the restoration works. Instead, father Zimmer with his young friend, a future painter Georg Kupke, made a copy of the painting, and - when forced by communist authorities to leave Silesia, smuggled the original wrapped in oilcloth with a coffee mug placed on top of it as if on a tray. Kupke, who leaved Wroclaw half a year earlier, reported later that he had visited his friend Zimmer twice in his flat at Bernau by Berlin in 1947 and in 1952, each time seeing the Madonna in his bedroom. Zimmer explained he was intending to pass the painting to the Catholic Church if he succeeded to get to the West, because in the Soviet occupation zone it might not be safe. However, when Zimmer found himself in Munich in 1954 where he had been delegated for theological studies, this did not happen. In the 1960s he sold the painting half legally to an antique dealer who was providing the cleric with Egyptian antiquities – his great hobby and passion. The fact that what had been left in Wroc?aw was a mere copy was only discovered in 1961 when the painting had to undergo conservation treatment before executing the color photograph, commissioned by a French publishing company. A shocking analysis was published in the professional monthly by the conservator Daniela Stankiewicz in 1965 (“Biuletyn Historii Sztuki”).

65 years of the odyssey tells about the paintings whereabouts on the “gray” art market, with various offers to public and private collections, about Georg Kupke’s private attempts to investigate and to spot the painting (described in the “Stern” magazine in 1985), about the joined proceeding of the German Episcopate Conference and the Wroclaw archbishop Henryk Gulbinowicz in 1981, aiming to prove that the ownership certificate presented with the bid was faked, about the official police investigation in Munich, which finally remained unsolved because of lack of proofs, and finally about a sensational letter from the Church at St. Gallen to the Wroclaw archbishop in February 2012, reporting on a donation of the Wroc?aw Madonna to them from an anonymous person and the decision of St. Gallen Catholic authorities to return the painting to its historical residence.

New Eve gives the description and the analysis of the painting, first commenting on a striking notice of the newspapers in July 2012, which sensationally remarked the dirt under Mary’s and Child’s nails as the result of the mother’s and child’s playing in the sand (!). This unusual detail, noticed by everybody who is privileged to see the painting in reality, instead of being a characteristics of unrefined realism, is rather a symbol emphasizing the incarnated God’s humility. The painting’s ideological message points to the redeeming mission of the Son of God and to the sacrament of the Eucharist, here suggested by the grapes which the Jesus Child is holding on his laps (symbolizing the Holy Blood) and Mary’s masterfully rendered, transparent veil, through which she is holding her baby, reminiscent of the ritual of the blessing with the Holy Sacrament by a clergyman who holds the monstrance not with his bare hands, but through a veil. The viewer has thus in front of his eyes the image of the adoration of the Redeemer’s body and blood. The image - because the parapet which is here an element of the composition, signalizes that the admired vision is but a picture and not an evocation of the real Holy Persons. It is aimed to help in contemplation not being a subject of the cult itself (which was to become a big problem of the Protestants).

The ideological message of the Virgin under the Fir Trees is a continuation and completion of Cranach’s painting Adam and Eve from the same period, i.e. from around 1510 (which was published in the previous, November issue of “Art&Business”). The young humanity, who lost Paradise through their disobedience, now finds the hope. The ancient tradition of biblical typology connects the figure of Eve with the figure of Mary. The liturgical text of the fourth preface about the Virgin Mary includes following words: “What Eve lost through her unfaithfulness, Mary recovered through her faith and has become a sign of consolation and strong hope for pilgrims on this Earth”. Cranach was conscious of this parallel: one of his later Virgins (in the collections of the Hermitage, ca. 1530) features a type of face similar to Eve from the Courtauld Institute in London (1526) and is placed under analogical apple tree, abundant in fruit, which is traditionally associated with a forbidden tree of the knowledge of good and evil.

The Wroclaw Madonna reflects artistic mastery of the early Wittenberg period of the Master in its full swing, shown in the chapter The new landscape. Voluminous figures, so unlike from Cranach’s later linear manner, betray Italian influence, with which the artist may had got acquainted in humanist circles in Vienna where he had sojourned in the first years of the 16th century. Similar images of the Virgin, both in their plasticity and the atmosphere of tenderness, represented against a background of a landscape and behind the parapet, were created by the famous Venetian painter Giovanni Bellini in the second half of the 15th century.

Also Netherlandish artists from the circle of Rogier van der Weyden painted the Virgin and Child in a landscape, but the Wroclaw Madonna differs essentially both from the Italian and Netherlandish realizations, although in turn Cranach’s precise detail and its realistic rendering originate from the latter tradition. The artist’s imitating skills are to be admired in the elements of vegetation, especially those in the foreground, in gray and white moss on the fir tree and in reproducing various materials: jewel-like decorations of the pillow, fringes, brocade and above all the transparency of Mary’s veil.

The main element in Cranach’s composition which distinguishes it from both Italian and Netherlandish painting is the landscape, representing typical Middle European nature of mountainous wilderness and coniferous woods. The wood was always a very important subject for Cranach, even if his visions of nature became more conventionalized in the1520s. The landscape in Wroclaw Madonna still belongs to the earlier, extremely creative and picturesque images of forests and wild mountains. It was the master’s painting from the Vienna period The Rest on the Flight to Egypt (1504) which decided about the opinion of him as being the initiator of the so called “Danube School”, credited with the introduction of the independent landscape painting. German forest appeared in paintings as something more than a background for the represented history. In this pioneering work the nature harmonizes with the story, reflecting the subject of the contemplation and even “cooperates” with the Holy Family securing a shelter for them. Saint Joseph himself is embraced, as if by a friendly arm, by a branch of a spruce tree!

Lucas Cranach the Elder and later Albrecht Altdorfer expressed in their paintings the interest of German humanists such as Konrad Celtis, Johannes Aventius or Ulrich von Hutten in “German forest”. This fascination was enlivened after the discovery in the Hersfeld abbey of a copy of Tacitus’ Germania and after its analysis in Rome by the future pope Pius II. This work became a source of myths and prejudices about inhabitants of this “hyperborean” forest country. The humanists however raised the legendary Hercinian Forest (Silva Hercynia) to the rank of the national attribute. It was above all Celtis, the creative reader of Tacitus, who changed the dismal interpretation of the forest – a milieu of ambivalent nature, arousing both the fascination and fear – into the pride of German people, a place of heroic deeds of knights, a temple and a seat of muses. But the forest is not only to be regarded as the seat of pagan cults – in paintings showing repenting saints: John the Baptist, Mary Magdalene, Anthony Abbot, Jerome – the forest wilderness is a place of contemplation and meeting with God.

This digression brings us back to Wroclaw Madonna. The forest here is marked but by two fir trees and young spruce bush on the right. Opposite from them a slender birch is bending as if in a bow to Mary’s head. According to authors writing about the early German landscape, the tree is the most essential element there, a link between the image and a place, at the same time being a metonymy of the entire German forest. The signs of the civilization in these landscapes are dominated and as if enveloped by trees. It is just what we observe in Wroclaw landscape: a miniature town between the firs and the distant mountains; on the left at the foot of fantastic rock formation crowned with a castle – equally minute figures of travelers, pack animals, small shrine, a cross. The firs, or rather overgrowth of moss on them, define the place as the northern side – Transalpinum, thus Cranach’s hic et nunc (here and now). At the same time the landscape goes beyond the region of the German forest toward the universality of Christendom. The images of nature were understood and interpreted, in the light of Saint Augustinus’ writings, as a metaphor of human pilgrimage through life – peregrination vitae - towards God’s City (Civitas Dei). The small human figurines shown in their toil, the high rock with a fortress make a compelling association with the pilgrim’s cry from the Psalm 31: “Be thou a rock of refuge for me, a strong fortress to save me!” On this hard and perilous road, for the “pilgrims on this Earth” it is the Madonna – the Mother of God who is the “sign of consolation and strong hope”.

[Hanna Benesz 2013]