English summary of the article 'Temat na pokuszenie' by Hanna Benesz, in „Art&Business”, no. 11/2012 (262), pp. 80-84

A Subject for Temptation

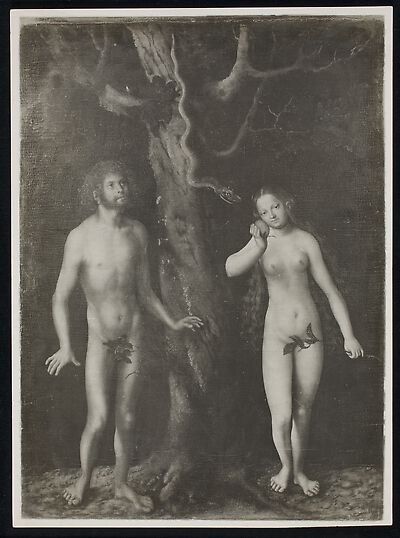

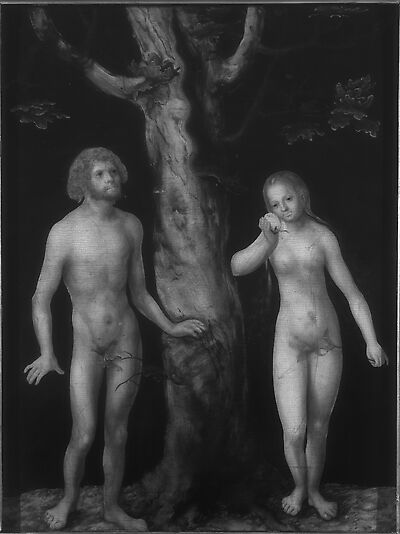

'In bold': Two nude figures under a tree against a backdrop of dark forest, in fact a treatise about good and evil, the beginning and the fall of humanity and at the same time a masterpiece of early modern European art, unveiling many inspirations and contexts. It’s Adam and Eve by Lucas Cranach the Elder.

It is to be admired in the Gallery of Old Masters newly reopened after a refurbishment on the occasion of the 150th anniversary of the Warsaw National Museum. An exceptional work both in Cranach’s oeuvre and in the whole period of Northern Renaissance, enthusiastically appreciated during two recent Cranach exhibitions (Frankfurt/London 2007-2008 and Brussels/Paris 2010-2011).

The chapter 'Artist and businessman' gives the biographical data and the scope of Cranach’s activity, mentioning his settling in Wittenberg and the Netherlandish journey of 1508, the influence of which is evident in the Altarpiece of the Holy Kindship, but also can be detected in "Adam and Eve".

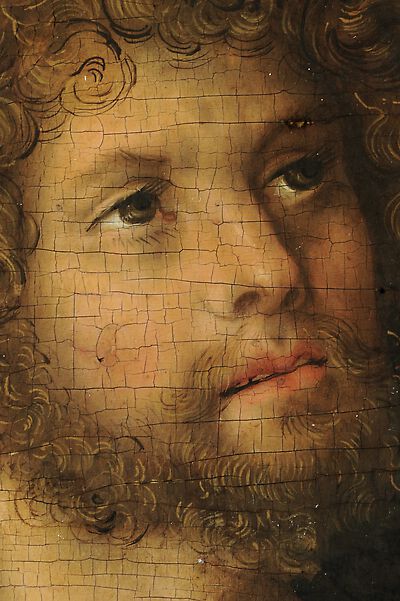

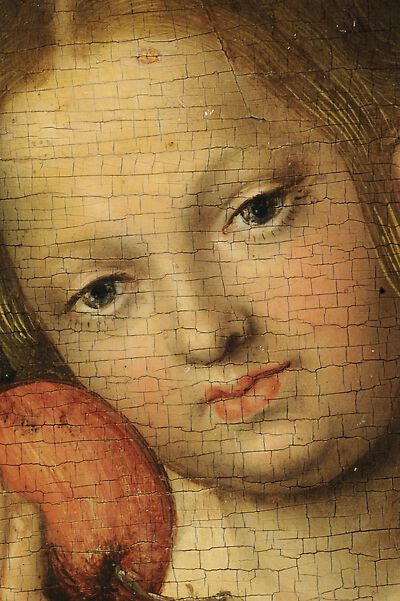

'Nudity – a tempting theme' presents the description and analysis of the painting, stressing the fact that it belongs to the most beautiful Cranach’s pictures featuring nudes of Italian inspiration all’antica inspired by Dürer (1504 engraving and the pair of paintings from Prado, 1507).

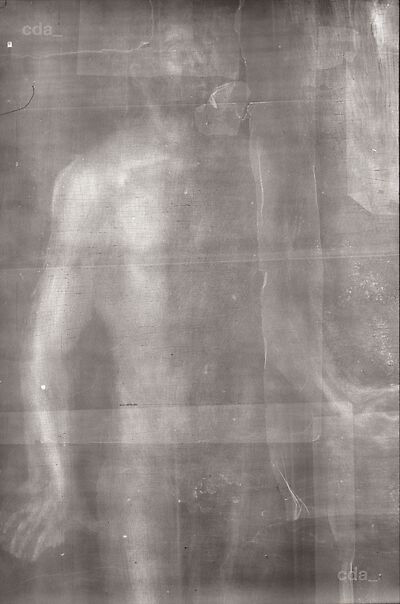

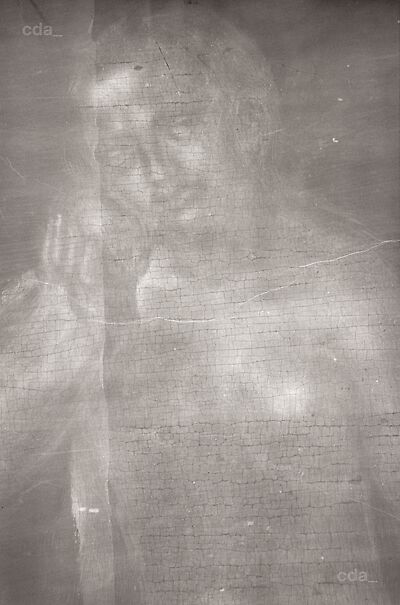

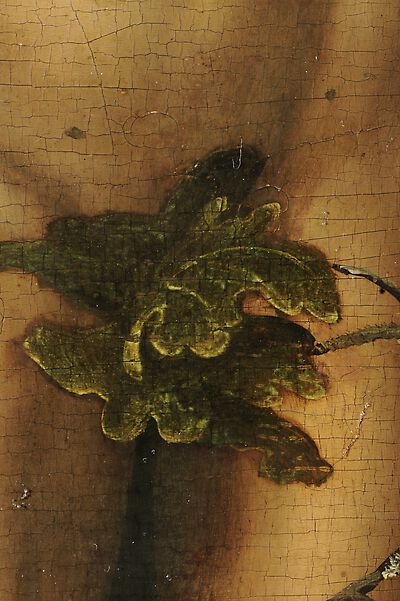

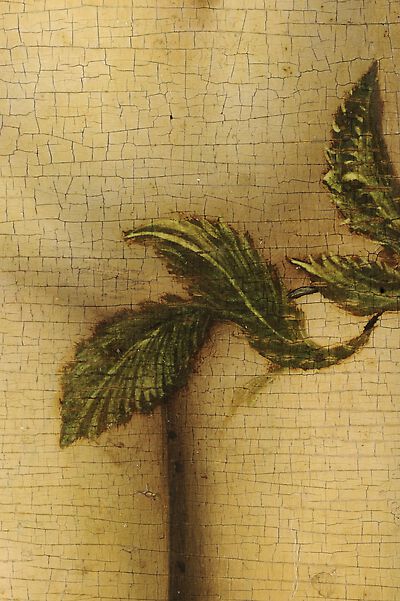

'The Drama in Paradise' emphasizes the psychological verity of the sin and fall, which Cranach attained here in a more successful manner than Dürer, for whom harmony of the composition was the most important goal. Adam’s perplexity expressed in his spread hands and in his face, Eve’s surrender to temptation, seen in her gaze directed to the viewer- as if announcement of shamelessness, contrasting with her still childish face, are masterfully rendered. The comparison with the IRR image proves that in his final realization Cranach decided for a more difficult challenge of showing the moment just before the fall, instead the one after – which is evident in infrared: the fruit has been bitten, the eyes are turned down, the sadness is profound. The text stresses further the juxtaposition of the classical, Italian element in the figures and the possible Netherlandish influence in psychological aspect: Cranach may had seen Van Eyck’s 'Mystic Lamb Altarpiece' in Ghent with touchingly unclassical, naturalistic figures of Adam and Eve who, however, emanate extraordinary psychological power. The tree of the knowledge of good and evil here represented by an oak instead of an Italian apple tree is connected with a tradition popular in the Netherlands, according to which Christ’s (New Adam’s) cross was executed in oak wood. The contrast between beautiful nudes of classical inspiration and wild, picturesque nature which is characteristic of Northern art adds special pictorial and ideological values. The nature here is not yet the naturalistically rendered “German forest” which serves as the background in numerous later versions of Cranach’s "Adam and Eve", especially those created after 1520. However, the monumental and expressive motif of the tree epitomizes the forest as the archaic, natural environment of aboriginal, “wild” people and reflects nostalgic feelings for the unspoiled world of the Golden Age, expressed by Cranach’s contemporaries such as Albrecht Altdorfer or Hans Sachs. The latter’s 'Lament of the Wild Man over the Unfaithful World' (illustrated with Hans Schäufelein’s travesty of the canonical Dürer’s Adam and Eve engraving!), quoted in the text in a big fragment, expresses the desire of turning away consequences of the expulsion from the Paradise and recovering the state of primeval innocence from before the fall. Similar, although epicurean, message is present in numerous Cranach’s paintings showing the Golden Age of Humanity, where in the midst of the beautiful Middle European nature small nude figurines are playing with one another among lazy wild animals.

'The grand career of Adam and Eve' relates the chronology of early representations of Adam and Eve in Cranach’s oeuvre, starting with Besançon panels for big, double paintings and the Warsaw model for the small, cabinet pictures, mentioning their several later versions created before 1515, all of them against a dark background and showing First Humans on both sides of the tree. After a break, recommencing in the mid 1520s the narrative versions follow, where protagonists are shown in woods, among animals, especially stags, with the stress laid on such qualities as decorativeness and elegance, quite distant from classical characteristics of the early paintings. The statistics of these versions reaches some thirty examples, the last one dated in 1549. The great popularity of this theme in Cranach’s oeuvre (especially after 1525) by various authors is explained with a twofold argument: the Lutheran doctrine of the mercy on one hand and the erotic attractiveness of beautiful nudes on the other.

[Hanna Benesz 2013]