- Attribution

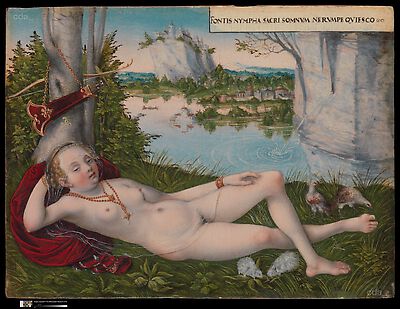

- Lucas Cranach the Younger

Attribution

| Lucas Cranach the Younger | [Cat. New York 2013, 94, No. 21] |

- Production date

- about 1545 - 1550

Production date

| about 1545 - 1550 | [Cat. New York 2013, 94, No. 21] |

- Dimensions

- Dimensions of support: 15.2 × 20.3 × 0.16 cm (6 × 8 × 1/16 in.)

Dimensions

Dimensions of support: 15.2 × 20.3 × 0.16 cm (6 × 8 × 1/16 in.)

[Cat. New York 2013, 94, No. 21]

- Signature / Dating

Artist's insignia at the centre left, on tree trunk: winged serpent with dropped wings

Signature / Dating

Artist's insignia at the centre left, on tree trunk: winged serpent with dropped wings

[Cat. New York 2013, 94, No. 21]

- Inscriptions and Labels

- in text field, at upper right:

'fontis nympha sacri somnvm ne rvmpe qviesco'

(I, nymph of the sacred spring, …Inscriptions and Labels

Inscriptions, Badges:

- in text field, at upper right:

'fontis nympha sacri somnvm ne rvmpe qviesco'

(I, nymph of the sacred spring, am resting; do not disturb my sleep)

[Cat. New York 2013, 94, No. 21]

- Owner

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

- Repository

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

- Location

- New York

- CDA ID

- US_MMANY_1975-1-136

- FR (1978) Nr.

- FR403B

- Persistent Link

- https://lucascranach.org/en/US_MMANY_1975-1-136/

- in text field, at upper right:

Provenance

Guillaume de Gontaut-Biron, Marquis de Biron, Paris (until 1908)

- sold to Kleinberger [1]

- [Kleinberger, Paris, 1908]

- [sold to Simon]

- James Simon, Berlin (from 1908) [2]

- Rudolf Chillingworth [3] Nuremberg and Lucerne, and/or his wife, [4] Paris (in 1927)

- [A. S. Drey, New York, until 1928]

- [sold to Lehman]

- Robert Lehman, New York (1928 - d. 1969)

- given to the Robert Lehman Foundation on his death and transferred to MMA in 1975); Robert Lehman Collection

[1] Kleinberger gallery stock card, no. 7932 (curatorial files, Department of European Paintings, MMA).

[2]Ibid. The painting was not offered at the Simon sale, Frederik Muller & Cie, Amsterdam, October 25 - 26, 1927.

[3] According to an invoice from A. S. Drey to Robert Lehman, dated New York, April 9, 1928 (curatorial files, Robert Lehman Collection, MMA).

[4]According to Friedländer and J. Rosenberg 1932, p. 89, no. 324b, which also supplies the date of 1927.

[Cat. New York 2013, 94, 293, No. 21]

Exhibitions

New York 1928, No. 27, ill. p. 21

George Henry McCall in New York 1939a, No. 58;

New York 1939b, No. 5, ill.;

Charles Sterling in Paris 1957, No. 10, pl. XXVII;

Cincinnati 1959, No. 119, ill.;

New York 1960, No. 7, ill.

Literature

| Reference on page | Catalogue Number | Figure / Plate | |||||||||||||||||

| Cat. Coburg 2018 | 92, fn. 20 | under no. 15 | |||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Exhib. Cat. Gotha, Kassel 2015 | 214 | ||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Waterman 2015 | 284, Fn. 19 - 287 | Fig. 5 | |||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Cat. New York 2013 | 94-97 | No. 21 | |||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Exhib. Cat. Brussels 2010 | 196 | ||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Exhib. Cat. Bremen 2009 | 33 | under no. 34 | |||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Matsche 2007 | 160, Fn. 3 | ||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Exhib. Cat. Münster 2003 | 30 | under no. 11 | |||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Cat. New York 1998 | 48-54 | No. 10 | Fig. | ||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Cat. Kassel 1997 | 92-94 | under no. 58 | Fig. 60 | ||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Cat. Kassel 1996 | 97 (Vol. 1) | ||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Cat. New York 1995 | 221 | Fig. | |||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Cat. Washington 1993 | 38, 39, Fn. 12, 20 | ||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Damisch 1992 | 136 | Fig. | |||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Cat. New York 1980 | 36-37 (Vol. 1) | Fig. p. 297 (Vol. 2) | |||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Hollander 1978 | 97 | Fig. | |||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Börsch-Supan 1977 | 21 | ||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Szabó 1975 | 89-90 | Plate 72 | |||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Talbot 1967 | 80, 87, Fn. 28, 29 | ||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Cat. Karlsruhe 1966 | 94-95 | under no.895 | |||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Metropolitan Museum 1960 | Fig. | ||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Preston 1960 | 272 | ||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Heinrich 1954 | 222 | ||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Kurz 1953 | 176, Fn. 2 | ||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Exhib. Cat. New York 1939 A | 5 | Fig. | |||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Frankfurter 1939 | 9-10 | Fig. | |||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Jewell 1939 | |||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Metropolitan Museum 1939 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Sweeney 1939 | 19 | Fig. | |||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Friedländer, Rosenberg 1932 | 89 | 324b | |||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Kleinberger Gallery 1928 A | 5 | ||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Mather 1928 | 310 | ||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

Research History / Discussion

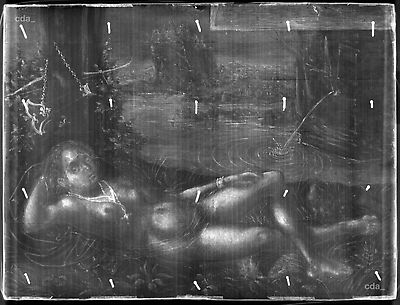

Like the Judgment of Paris and Venus with Cupid the Honey Thief (see cats. 11, 20), the Nymph of the Spring counts among the most popular mythological subjects treated by Lucas Cranach the Elder and his workshop. The present panel, which is most probably by Lucas Cranach the Younger, is one of at least seventeen versions that survive. They date from the mid-1510s to about 1550.[1] In the two earliest examples, a panel dated 1518 in the Museum der Bildenden Künste Leipzig, and one of about 1515 – 20 in the Jagdschloss Grunewald, Berlin,[2] the spring (fons) is depicted as a man-made fountain basin, with the inscription (the nymph’s address to the viewer) painted as if carved into it. From about the mid-1520s onward, however, the nymph lies before a natural spring flowing from a rock, the inscription is no longer fashioned as a fictive carving, and a bow and quiver, partridges, and, frequently, stags appear as accessories.[3]

Authors have detected in this subject matter an ambivalence between the sensual allure of the nude figure and her admonition not to disturb her rest, which is comparable to the moralizing aspect of the Venus with Cupid the Honey Thief paintings.[4] As Franz Matsche noted, the Cranach nymphs are thus connected with the courtly ideal of control of the emotions and with the Christian and humanist concern for the restraint of carnal desire.[5] In the case of the Museum’s picture, these ideas appear to be at play not only in the iconography but also in the intimate viewing experience, for its small size and minute execution encourage the viewer to approach within just inches of the seductive nymph.

The subject matter appears to have originated in a pseudoclassical Latin epigram thought to have been composed by the Roman humanist Giovanni Antonio Campano before 1465.[6] It reads, Huius nympha loci sacri custodia fontis / Dormio dum blandae sentio murmur aquae. / Parce meum quisquis tangis cava marmora somnum / R umpere; sive bibas sive lavere tace. (I, the nymph of this sacred place, keeper of the spring, am sleeping and listening to the endearing murmur of the water. Take care, whoever approaches this marmoreal cave, not to disturb my sleep; whether you drink or bathe, keep silent!)

The passage found its way into many contemporary compilations and, its modern origin mostly forgotten, rapidly became one of the most widespread of all pseudoclassical epigrams.[7]

Evidence that it was current north of the Alps reaches back to the 1470s at the court of King Matthias Corvinus of Hungary (r. 1458 – 90). In a compendium drawn up before 1486, Michael Fabricius Ferrarinus, prior of the Carmelite monastery in Reggio Emilia, remarked that the Huius nympha loci quatrain was to be found carved beneath the figure of a sleeping nymph on a fountain “on the banks of the Danube” (super rippam danuvii).[8] For fifteenth-century Italian humanists like Ferrarinus, the Danube River was associated with the ancient Roman province of Pannonia, or modern Hungary; thus, Ferrarinus’s reference may well have been to a fountain monument in Buda erected by Matthias Corvinus and since lost.[9] Further awareness of the epigram in northern Europe is documented in the literary remains of imperial poet laureate and humanist Conrad Celtis.[10] Also, Albrecht Dürer, an acquaintance of Celtis, reproduced the full passage in a drawing of 1514 (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna).[11] The Cranach paintings of the theme reduce the epigram to a single-line abridgment, “Fontis nympha sacri somnvm ne rvmpe qviesco,” which raises the question of a variant textual or epigraphic source.

In 1974 Dieter Koepplin broached the possibility that Lucas Cranach the Elder knew of an actual sculpted fountain nymph “on the banks of the Danube,”[12] and recently Franz Matsche and Zita Ágota Pataki drew renewed attention to Matthias Corvinus’s fountain.[13] Matsche maintained that Cranach might have encountered it firsthand on a trip to Buda about 1502 – 4, when he resided in Vienna. As evidence, Matsche cited a description written by the Hungarian humanist Thomasus Jordanus, in which the fountain’s inscription is recorded not as the usual four-line epigram but instead as a couplet whose first line is the same as the verse on Cranach’s paintings, which suggests that the monument described by Jordanus was Cranach’s source.[14] Pataki cast doubt on the historical and epigraphical accuracy of Jordanus’s note, but she nevertheless maintained the value of his remarks as evidence of the fountain’s existence in Buda.[15] Concerning Cranach, she proposed a transfer of knowledge of the Buda fountain to the artist along humanist channels.[16]

Whereas the extent and manner of influence of the Buda fountain on Cranach is difficult to gauge, it is clear that the reclining pose he used for most of his nymphs derives from a woodcut published in Francesco Colonna’s Hypnerotomachia Poliphili (Venice, 1499) that shows an imaginary nymphean fountain (fig. 76).[17] In the book illustration and the majority of Cranach’s paintings, the nymph supports her head with her right hand, rests her left hand on her left thigh, and crosses her left leg over her right. The bow and quiver, which appear commonly in paintings after 1525, find a precedent in a 1510 engraving by Giovanni Maria Pomedelli (fig. 77).[18] That print, which shows a reclining nymph in a landscape surrounded by animals in repose (except for the retreating boar with an arrow in its rump), is inscribed Qvies (quietude) and thus emphasizes the notion of rest after the hunt found also in Cranach’s pictures. Other proposed sources of influence are less direct but nevertheless demonstrate a growing interest in the reclining female nude in the years before the first appearance of Cranach’s fountain nymphs.[19]

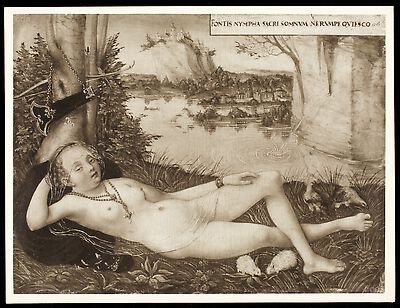

In the 1998 catalogue of the Lehman Collection, Charles Talbot convincingly ascribed the Nymph of the Spring to Lucas Cranach the Younger and rightly noted that its high quality sets it apart from routine workshop production.[20] The folded wings of the serpent insignia on the tree trunk confirm a date after 1537, when the Cranachs began using that form of the mark. The overall bright tonality, the gray undermodeling of the flesh, visible with the naked eye and infrared imaging (fig. 78), the paleness of the flesh tone, and the exaggerated local reddening all speak in favor of an attribution to Lucas the Younger. The dimensions of the Museum’s picture associate it with a group of small panels[21] produced in the second half of the 1540s that share a doll-like quality of the figures and a pronounced rosiness in the faces (discussed in greater detail in the next entry, cat. 22a, b). This group is also close to certain contemporary large-scale pictures that have been attributed to Lucas Cranach the Younger, such as Elijah and the Priests of Baal of 1545 (Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden) and Saint John the Baptist Preaching of 1549 (Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum Braunschweig).[22] The dates of the comparative works suggest a likely range of about 1545 – 50 for the Museum’s Nymph of the Spring, slightly earlier than the dating of about 1550 proposed by Talbot.

The composition of the Museum’s Nymph of the Spring served as the basis for three copies. While those in the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Kassel (fig. 79),[23] and a private collection were probably produced within the workshop,[24] the one in the Staatliche Kunsthalle Karlsruhe appears to be by a copyist of the late sixteenth or early seventeenth century.[25]

[1] Talbot in ibid., p. 49; a listing is provided in Hand 1993, pp. 38 – 39, n. 12.

[2] Schade 1974, pls. 97, 93; Friedländer and J. Rosenberg 1978, p. 93, nos. 119, 119A; Elke Werner in Berlin 2009 – 10, pp. 197 – 98, no. III.16, ill. (Berlin version).

[3] First in a drawing of about 1525 formerly in the Kupferstich-Kabinett, Dresden ( J. Rosenberg 1960, p. 22, no. 40, ill.; missing since World War II). An exception is the version dated 1534 in the Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool (Friedländer and J. Rosenberg 1978, p. 121, no. 259, ill.), which shows a fountain basin instead of a spring. For fuller discussions of the iconographic changes, see Dieter Koepplin in Basel 1974, vol. 2, pp. 635 – 36; Lübbeke 1991, pp. 207 – 9; Talbot in Sterling et al. 1998, pp. 51 – 52; Matsche 2007, pp. 190 – 95.

[4] See Talbot 1967, pp. 81 – 84; Koepplin in Basel 1974, vol. 2, p. 635; Matsche 2007, pp. 202 – 3; Werner in Brussels and Paris 2010 – 11, p. 196, under no. 112.

[5] Matsche 2007, pp. 202 – 3. Learned viewers may also have drawn parallels with the nine Muses, the goddesses of intellectual pursuits who were originally protectresses of inspiration-giving springs. Furthermore, that Cranach’s nymphs do not actually sleep, but instead appear to be caught in a state of reverie, suggests that they were meant to evoke the notion of contemplative inspiration. For discussion of these matters, including the combination of frank eroticism with humanist moral and intellectual concerns, see Lübbeke 1991, pp. 206 – 7; Pataki 2005, vol. 1, pp. 294 – 303; Matsche 2007, pp. 192, 200 – 201.

[6] For the dating, see Pataki 2005, vol. 1, pp. 39 – 40. The attribution to Campano was made by the Florentine humanist Bartolomeo della Fonte, who, in the earliest known record of the epigram (in a compilation of 1464 – 70), noted: “Romae recens inventum. Campani est” (Recently invented in Rome, it is by Campano); see MacDougall 1975, p. 358; Pataki 2005, vol. 1, pp. 32 – 33, vol. 2, p. 335, no. 1; Matsche 2007, p. 170. As MacDougall, Pataki, and Matsche noted, “inventum” and “Campani est” may alternatively be interpreted as “found” and “It belongs to Campano,” which would suggest that Campano merely discovered the epigram, presumably as an ancient inscription carved in stone. Nevertheless, the general consensus is that Campano devised it.

[7] See MacDougall 1975, pp. 358 – 59; Pataki 2005, vol. 1, p. 45.

[8] See MacDougall 1975, pp. 357, 358 – 59; with several corrections, Pataki 2005, vol. 1, pp. 45 – 64, vol. 2, pp. 336 – 37, no. 3.

[9] Aided by the work of the historian Ágnes Ritoók Szalay (Ritoók Szalay 1983/2002), Zita Ágota Pataki (see Pataki 2005, vol. 1, pp. 45 – 64) maintained that Ferrarinus, who was not a traveler, could have learned of the fountain from the antiquarian Felice Feliciano, who probably visited Hungary in 1479.

[10] Wuttke 1968, p. 306; Matsche 2007, pp. 167 – 68.

[11] Winkler 1936 – 39, vol. 3 (1938), p. 79, no. 663, ill.; Kurz 1953, pp. 171 – 72.

[12] Koepplin in Basel 1974, vol. 1, p. 428.

[13] Matsche 2007; Pataki 2005, vol. 1, pp. 74 – 83. Matsche and Pataki based their studies on the historical groundwork in Ritoók Szalay 1983/2002.

[14] “Fontis nympha sacri, somnum ne rumpe, quiesco. / Dormio dum blandae sentio murmur aquae”; Matsche 2007, p. 177. Jordanus’s note was not, as Matsche claimed, published in a historical chronicle in 1585; rather, it is a handwritten entry of about 1569 on the flyleaf of Jordanus’s copy of Gáspár Heltai’s Historia inclyti Matthiae Hvnnyadis, Regis Hungariae (Claudiopolis [Cluj-Napoca], 1565); see Pataki 2005, vol. 1, pp. 49 – 50, vol. 2, p. 342, no. 14.

[15] Pataki 2005, vol. 1, pp. 50, 275 – 76.

[16] Namely, via Conrad Celtis or the Hungarian Thurzó family. See ibid., pp. 74 – 83.

[17] As first noted in Liebmann 1968, pp. 435 – 37. See also Koepplin in Basel 1974, vol. 2, p. 639, no. 549, fig. 238; Matsche 2007, pp. 160 – 63, fig. 2; Werner in Brussels and Paris 2010 – 11, pp. 195 – 96, no. 110, ill.

[18] Hind 1938 – 48, vol. 5 (1948), p. 225, no. 1, vol. 7 (1948), pl. 807; Koepplin in Basel 1974, vol. 2, p. 637, under no. 544; Matsche 2007, pp. 186 – 90, fig. 6; Werner in Brussels and Paris 2010 – 11, pp. 195 – 96, no. 111, ill. Cranach’s earliest use of the bow and quiver motif was in a drawing of a fountain nymph of about 1525 formerly in the Kupferstich-Kabinett, Dresden ( J. Rosenberg 1960, p. 22, no. 40, ill.; missing since World War II).

[19] The proposed sources are Giorgione and Titian’s Sleeping Venus, ca. 1508 – 10, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden (Glaser 1921, pp. 100 – 102; Friedländer and J. Rosenberg 1978, p. 93, under no. 119; Talbot in Sterling et al. 1998, p. 50; Evans [Mark] 2007, p. 56); a lost Giorgione depicting a reclining Venus or nymph after the hunt (Kurz 1953, p. 176; Evans [Mark] 2007, p. 56); the ancient Roman Sleeping Ariadne statue installed in the Belvedere court of the Vatican in 1512 (Koepplin in Basel 1974, vol. 1, p. 428); and the above-mentioned drawing of a fountain nymph by Dürer in the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna (Koepplin in Basel 1974, vol. 1, p. 428). Edgar Bierende (2002, pp. 226 – 34) maintained that the theme was connected with legends of an ancient miracle-working spring near Meissen.

[20] Talbot in Sterling et al. 1998, pp. 48 – 54, no. 10, especially pp. 52 – 53. This attribution had already been proposed in Friedländer and J. Rosenberg 1932, p. 89, no. 324b; H. Börsch-Supan 1977, p. 21; Friedländer and J. Rosenberg 1978, p. 150, no. 403B. Earlier Lehman Collection and Metropolitan Museum cataloguing gave the picture to Lucas Cranach the Elder; see Szabó 1975, pp. 89 – 90; Baetjer 1980, vol. 1, pp. 36 – 37; Baetjer 1995, p. 221.

[21] The panel sizes are generally consistent with the standard Cranach panel format A (18.5 – 22.5 × 14 – 16 cm), according to the categorization in Heydenreich 2007b, p. 43.

[22] Karin Kolb in Chemnitz 2005 – 6, pp. 236 – 45, no. 7, ill. (Dresden); Schade 1974, pl. 212 (Braunschweig).

[23] Schneckenburger-Broschek 1997, pp. 88 – 94, no. 58, ill.

[24] Kurt Löcher in Münster 2003, pp. 30 – 32, no. 11, ill.

[25] Lauts 1966, vol. 1, pp. 94 – 95, ill. vol. 2, p. 33; Holger Jacob-Friesen in Bremen 2009, pp. 33 – 34, no. 34, ill.

[Waterman, Cat. New York 2013, 95,96,97, 293, 294, No 21]