The story of Samson and Delilah is one of the biblical and classical subjects that were seen to exemplify the power or wiles of women (Weibermacht, Weiberlisten) and as such were popular in medieval and Renaissance art and literature.[1] They include David and Bathsheba, Solomon’s Idolatry, Hercules and Omphale, Aristotle and Phyllis, and Virgil in a Basket, among others. The theme presented an admonitory and often humorous inversion of the male-dominated sexual hierarchy. In northern European art, such scenes of heroic or wise men dominated by women appeared first in the decorative arts of the fourteenth century and were often grouped in series, as in the Malterer Embroidery of about 1320 – 30 (Augustinermuseum, Freiburg), which displays several power of women subjects, including Samson and Delilah.[2] During the fifteenth century the power of women theme remained popular in the decorative arts, from small-scale sculpture to wall painting, and by the early sixteenth century, engravings and woodcuts by the Master E.S., Lucas van Leyden, Hans Burgkmair, and others had facilitated the spread of the theme. As Koepplin pointed out, Lucas Cranach the Elder was the first northern artist to treat many of these subjects, found previously only in the decorative and graphic arts, in the elevated medium of panel painting.[3] Such is the case with Samson and Delilah, of which the Metropolitan Museum’s version is one of three known examples produced by Cranach and his workshop, the others being the 1529 panel by Cranach in the Kunstsammlungen und Museen Augsburg (fig. 51),[4] and the panel of about 1537 – 40 attributed to Lucas Cranach the Younger in the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden.[5]

The Museum’s Samson and Delilah became known only in 1961, when it appeared on the art market as a work of Lucas Cranach the Elder.[6] Jakob Rosenberg — apparently unaware of the serpent insignia on the tree stump, whose raised wings indicate a date before 1537 — suspected the authorship of Lucas the Younger and a date of about 1540 in association with the Dresden panel.[7] Koepplin, however, assigned it to Lucas the Elder, placing it after the Augsburg version but rejecting 1540 as too late.[8] Guido Messling saw the painting as a work by the elder Cranach, of about 1530, and noted that Lucas van Leyden’s woodcut of the same subject of about 1514 provided the basic compositional model (fig. 52).[9] The Museum’s own publications have favored an attribution to Cranach the Elder.[10]

The Metropolitan’s Samson and Delilah is stylistically consistent with the Augsburg example and surely dates about the same time; however, the prevailing opinion that it must fall somewhat later than 1529 appears to rest solely on the assumption that certain compositional differences in the present version — for example, the more compressed, planar space, the higher horizon that leaves less room for background detail, and the more blocklike group of Philistines — must represent a degeneration from the grander, more elaborate Augsburg picture. Yet those differences may have less to do with chronological sequence and stylistic development than with the relative importance and expense of the commissions. The large Augsburg panel appears to have been a highly prestigious commission; it has an old provenance from the city’s town hall, for which it may have been ordered.[11] Although the original circumstances of the Metropolitan’s version are unknown, it is obviously a more modest work. The design features that make it appear less accomplished than the Augsburg painting may simply be the result of a less labor-intensive execution at a lower cost. As there is no clear logic of compositional dependency from one picture to the other, the question of which came first remains open.

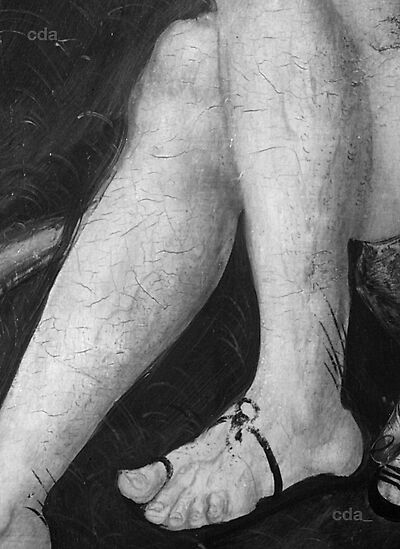

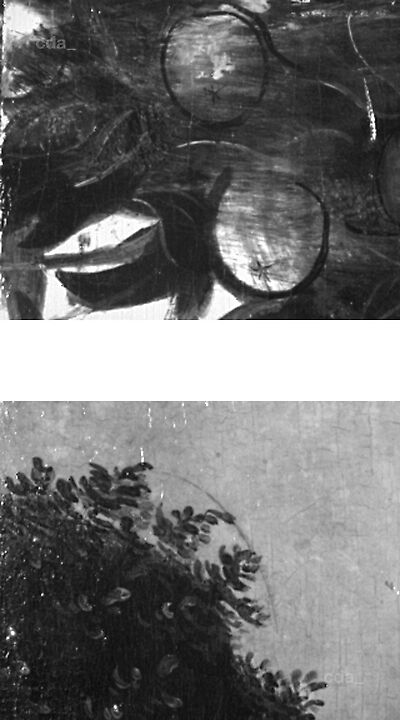

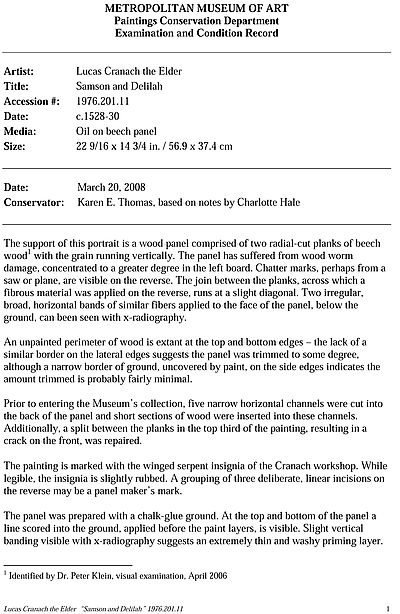

Comparison with other dated works from the same period suggests a range of about 1528 to 1530 for the Museum’s picture. The 1528 Lot and His Daughters (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna) and the 1530 Aristotle and Phyllis (private collection), which are of the same format, both show striking similarities in composition, palette, drapery folds, and figure and costume types.[12] A dating of about 1528 – 30 is furthermore consistent with the results of dendrochronological analysis of the Museum’s panel, which indicates an earliest possible fabrication date of 1525. Of special interest on the verso is the H-like mark carved into the top center; it was possibly executed by the panel maker and is illustrated here in the interest of identifying similar examples on other works by Cranach (fig. 53).

Contemporary sources indicate that the Samson and Delilah story was commonly understood as an admonition against divulging secrets, for Samson’s disclosure of the source of his strength left him vulnerable to his archenemies. Sebastian Brant’s Narrenschiff (Ship of Fools), first published in Basel in 1494, popularized this interpretation; in the fifty-first chapter, a woodcut of Delilah clipping Samson’s hair illustrates the verse, “He who cannot keep a secret / And reveals his intentions to another / Will experience regret, harm, and suffering.”[13] Indicative of the idea’s cultural prevalence is the appearance of Samson and Delilah on a baking mold dated 1510 with the epigram, “Had you kept your secret, you would not have been harmed.”[14] This was of particular relevance in the town-hall context of the Augsburg panel, where the subject would have reminded municipal officials not to divulge confidential matters of government.[15] Albrecht Dürer’s 1521 design for the mural decoration of Nuremberg’s town hall, which depicts Samson and Delilah as part of a larger program of power of women themes, further demonstrates the subject’s pertinence in a public civic context.[16]

The smaller size of the Museum’s picture seems less appropriate to a town-hall setting and suggests a more private display context, in which it might have conveyed its message of secrecy alongside other subjects that dealt with the folly of love and the power of women.

This would follow a precedent set, for example, by the decoration of the 1513 nuptial bed of Duke Johann of Saxony (later Elector Johann I; r. 1525 – 32), which Cranach is reported to have painted with various admonitory mythological and biblical scenes, including the Judgment of Paris, Hercules and Omphale, and Solomon’s Idolatry.[17] The power of women series by Lucas Cranach the Younger (Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden), which includes the later Samson and Delilah panel noted above, was probably commissioned by Elector Johann Friedrich I of Saxony (r. 1532 – 47)[18] and attests to a sustained interest in those themes among the workshop’s most important patrons. The Museum’s picture may also have served as a foil for a heroic depiction of Samson. In particular, Cranach’s Samson Slaying the Lion in the Schlossmuseum Weimar (fig. 54) goes well with the painting in New York; the dimensions match, the design is comparable, and the style also points to the late 1520s.[19] A pairing of those two scenes would have emphasized the magnitude of Samson’s descent from heroism to folly.[20]

[1] See S. L. Smith 1995; Bleyerveld 2000; Bleyerveld 2010; on Samson and Delilah in particular, see Kahr 1972.

[2] Eissengarthen 1985, pp. 23 – 30, ill.

[3] Koepplin in Basel 1974, vol. 2, p. 573, under no. 471; on such “ennoblement” as a guiding principle for Cranach, see Koepplin 2003a.

[4] Friedländer and J. Rosenberg 1978, p. 111, no. 212, ill.; see also Koepplin in Basel 1974, vol. 2, pp. 573 – 74, no. 471, fig. 295; Schawe 2001, pp. 38, 70, 82, fig. 69.

[5] Friedländer and J. Rosenberg 1978, p. 140, no. 357E; see also Koepplin in Basel 1974, vol. 2, p. 574, no. 472, fig. 297; Karin Kolb in Chemnitz 2005 – 6, pp. 218 – 23, no. 4, ill.

[6] Sotheby’s 1961, p. 47, no. 107.

[7] Friedländer and J. Rosenberg 1978, p. 111, no. 213; a view repeated by H. Hoffmann 1990, p. 60, under no. 19.

[8] Koepplin in Basel 1974, vol. 2, p. 574, under no. 471; Koepplin 2003a, pp. 147, 162, n. 23.

[9] Messling in Brussels and Paris 2010 – 11, p. 217, no. 124, ill. The Lucas van Leyden woodcut is in Filedt Kok 1996, p. 157, no. 176.

[10] See Baetjer 1980, vol. 1, p. 36; Metropolitan Museum 1987, p. 109; Baetjer 1995, p. 221.

[11] See Koepplin in Basel 1974, vol. 2, pp. 573 – 74, no. 471.

[12] For the work in Vienna, see Friedländer and J. Rosenberg 1978, p. 110, no. 206, ill.; see also Karl Schütz in Vienna 1972, pp. 21 – 22, no. 8, fig. 7. For the one in a private collection, see Bernard Aikema in Rome 2010 – 11, pp. 247 – 48, no. 38, ill.

[13] “Wer nit kan schwygen heymlichkeyt / Vnd syn anschlag eym andern seyt / Dem widerfert, rüw, schad, vnd leydt” (Brant 1494/2004, p. 125; noted in H. Hoffmann 1990, p. 60).

[14] “Hettestu verswigen dein heimkeit so were dir nit geschen leid” (noted by Koepplin in Basel 1974, vol. 2, p. 574, under no. 471).

[15] This interpretation of the Augsburg picture was intimated by Eckhard von Knorre in Bushart 1967, p. 60; see also Jachmann 2008, p. 122.

[16] The Morgan Library & Museum, New York (see Winkler 1936 – 39, vol. 4 [1939], p. 92, no. 921, ill.; Barbara Drake Boehm in New York and Nuremberg 1986, pp. 329 – 30, no. 146, ill.).

[17] Bauch 1894, pp. 424 – 25; Koepplin in Basel 1974, vol. 2, p. 563; Arnulf 2004, pp. 558 – 61.

[18] See Kolb in Chemnitz 2005 – 6, pp. 218 – 35, nos. 4 (Samson and Delilah), 5 (David and Bathsheba), 6 (Solomon’s Idolatry), ill.

[19] Friedländer and J. Rosenberg 1978, p. 97, no. 140, ill.; H. Hoffmann 1990, pp. 28 – 29, no. 8, ill. In my opinion, the dating about 1520 – 25 maintained by Friedländer and Rosenberg and by Hoffmann is too early. A smaller version is in a private collection (Friedländer and J. Rosenberg 1978, p. 97, no. 140A; see also Koepplin in Basel 1974, vol. 1, pl. 20, vol. 2, p. 607, no. 514).

[20] The juxtaposition had already appeared in medieval power of women iconography, for example, in the Malterer Embroidery in Freiburg cited above and a southern German tapestry fragment of about 1420 – 30 in the Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nuremberg (Bleyerveld 2000, fig. 6).

[Waterman, Cat. New York 2013, 59, 60, 62, 287, 288, No. 12]