- Attribution

- Workshop Lucas Cranach the Elder

Attribution

| Workshop Lucas Cranach the Elder | [Ainsworth / Waterman 2013, p. 85, No. 18] [KKL 2022] |

- Production dates

- about 1530

probably 1532

Production dates

| about 1530 | [KKL 2022] |

| probably 1532 | [Ainsworth / Waterman 2013, p. 85, No. 18] |

| about 1535 | [Kuhn 1936, No. 143] |

- Dimensions

- Dimensions of support: 33.3 × 23.2 × 0.6 - 0.8 cm (13 1/8 × 9 1/8 × 1/4 - 5/16 in.)

Dimensions

Dimensions of support: 33.3 × 23.2 × 0.6 - 0.8 cm (13 1/8 × 9 1/8 × 1/4 - 5/16 in.)

[Cat. New York 2013, 85, No. 18]

- Inscriptions and Labels

Reverse of the panel: - at upper left:

in graphite, '11029'- at upper right:

in graphite, '196-27' - at centre:

in chalk(?), …Inscriptions and Labels

Stamps, Seals, Labels:

Reverse of the panel: - at upper left:

in graphite, '11029'

- at upper right:

in graphite, '196-27'

- at centre:

in chalk(?), '6'

- at centre:

twice on masking tape, in grease pencil(?) and graphite, '55.220.2'

[Ainsworth / Waterman 2013, p. 85, No. 18]

- Owner

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

- Repository

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

- Location

- New York

- CDA ID

- US_MMANY_55-220-2

- FR (1978) Nr.

- FR314F

- KKL-No

- V.M2, Part of portait group V

- Persistent Link

- https://lucascranach.org/en/US_MMANY_55-220-2/

- at upper right:

Provenance

- ? [art market, in 1927]

- Robert Lehman, New York (by 1928 - 55)

- Gift of Robert Lehman, 1955

[Ainsworth / Waterman 2013, No. 18]

Exhibitions

New York 1928, No. 31

on loan to Smith College, Northampton, Massachusetts, 1942 - 43

New York 1946, No. 2

Fisk University, Nashville, 1961 (no catalogue)

Literature

| Reference on page | Catalogue Number | Figure / Plate | |||||||||||||||

| Cat. New York 2013 | 85-87 | No. 18 | |||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

| Cat. New York 1995 | 223 | Fig. | |||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

| Cat. New York 1987 | 106 | Plate 74 | |||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

| Cat. New York 1980 | 37 (Vol. 1) | Fig. p. 297 (Vol. 2) | |||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

| Friedländer, Rosenberg 1979 | No. 314F | ||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

| Exhib. Cat. Cambridge, Mass. 1936 | 44 | 143 | Plate XXXVI | ||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

| Friedländer, Rosenberg 1932 | 75 | 252k | |||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

| Kleinberger Gallery 1928 A | 5 | ||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

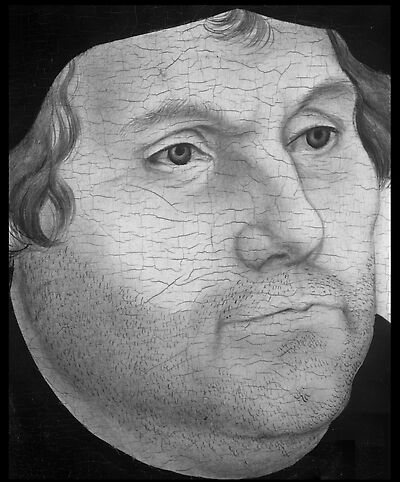

Research History / Discussion

This is one of the many printed and painted portraits of Martin Luther (1483-1546) that were produced by Cranach and his workshop beginning about 1520. The reformer and the artist were well acquainted, for Cranach served as Luther's matchmaker (Brautwerber) when he was courting Katharina von Bora, who lived in Cranach's house in Wittenberg from 1523 until her marriage to Luther in 1525. Luther also served as the godfather of Cranach's first daughter, born in 1520.

Deeply involved with the production of images for the Protestant Reformation, Cranach made illustrations for the Bible, including for Das Neue Testament deutsch (Wittenberg, 1522) and for Luther’s sermons, lectures, polemical tracts, and broadsheets. He also painted a number of pictures and altarpieces supporting Protestant viewpoints, among them portraits of Luther that varied according to the purposes they were meant to serve.[1] In 1532 Cranach paired a half-length view of Luther facing right with one of Philipp Melanchthon facing left; of the several versions of this pairing, the pendants in the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden, are considered the primary examples.[2] Melanchthon, of course, was Luther’s main collaborator, a theologian and intellectual leader of the Reformation. The Museum’s Luther is a subtype of this group, showing a close-up view and a more tightly cropped image that was probably joined with a portrait of Melanchthon.[3] An extant pair in the Gemäldegalerie, Berlin (fig. 69a, b), is very similar in dimensions (37 by 24.6 centimeters and 37 by 23.5 centimeters) to the Metropolitan’s painting (33.3 by 23.2 centimeters, the shorter vertical measurement owing to the panel’s having been cut at the lower edge).[4]

Kurt Löcher suggested that this portrait type of Luther emerged in 1532 because of the new Protestant “state of awareness” (Bewusstseinsstand) that resulted from the 1530 Imperial Diet at Augsburg.[5] With that convocation and the presentation there of the Confessio Augustana (Augsburg Confession), he noted, Lutheran Protestantism came to be seen as an “independent confession and church” separate from Roman Catholicism.[6] In the 1532 portrait type, Luther is shown wearing the distinctive black Protestant vestments and in a mood of “calm persuasiveness,” which has replaced the militant demeanor and features of Cranach’s early portraits of him, including the 1520 engraving Luther as Augustinian Monk and the 1522 woodcut Junker Jörg.[7] The pairing with the Melanchthon portrait, Löcher suggested, may also be related to the Diet of Augsburg: it was Melanchthon who drew up the Augsburg Confession and presented it as a representative of electoral Saxony and of the Protestant Estates.[8] As Kira Judith Kokoska has expressed it, “The intention of pairing the two main Reformers of Wittenberg was likely to represent pictorially the unity of the Protestant movement and the legitimacy of the doctrine which Melanchthon had worked out and set in canonical form.”[9] She further asserted that the granting of imperial concessions to the Protestants in the 1532 Peace of Nuremberg may have driven demand for this particular portrait type and resulted in the need for its increased production.[10] The pairing of Luther and Melanchthon may also derive, as Löcher theorized, from humanist friendship portraits such as Quentin Metsys’s 1517 depictions of Erasmus and Peter Gillis (Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Antica, Palazzo Barberini, Rome, and Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Antwerp).[11] Seeing a parallel with the paired portraits of Electors Friedrich the Wise and Johann the Constant (cat. 17a – c), Löcher imagined the electoral Saxon court as the motivating force behind the 1532 Luther and Melachthon portraits and regarded their purpose as propagandistic, to spread the “image” of the “spiritual representatives and authorities.”[12] Though the paired Luther and Melanchthon portraits must have established the idea of the reformers and the Reformation as an institution, how they specifically related to particular propagandistic aims is not completely clear. As Robert Scribner argued with regard to the post-1540s propagandistic prints of the Reformation, such images were “less a matter of establishing an evangelical movement, and more of consolidating it.”[13] The “calm persuasiveness,” as Löcher termed it, of the Luther and Melanchthon portraits more likely served to sustain the idea of a newly established Reformation and to maintain the morale of its proponents.[14]

Although Max J. Friedländer first considered the Museum’s Luther an autograph work by Cranach from about 1530,[15] this attribution was reevaluated over the years owing to the preponderance of versions and workshop copies.[16] The painting does indeed exhibit the rather dry, hard contours and stiff rendering of a copy. There are five other known versions of closely similar size, four of which are in oil on panel (sold at Christie’s, London, July 7, 1972, lot 75; Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen; Gemäldegalerie, Berlin; Universitätsmuseum für Bildende Künste, Marburg) and one watercolor on parchment (Duke of Buccleuch Collection, Boughton House). The formerly Christie’s and Copenhagen versions both carry Cranach’s insignia and the date 1532.[17] The Museum’s painting is most similar to the Copenhagen version and to the drawing in the Buccleuch Collection (fig. 70). There is a particularly close correspondence between our painting and the drawing — in the wavy contour of the head at the right, in the modeling of the face, in the specific arrangement of the locks of hair at the left, and even in the stubble of the beard, a feature shared with none of the other painted versions.

In fact, when an exact scale digital image of the drawing is superimposed onto the Metropolitan’s painting, the two so nearly match that they must have either a direct or indirect relationship to each other. However, there is no visible evidence that the design for the Museum’s portrait was transferred from a cartoon, and it is possible that the tonal underpainting in gray washes in the head (see technical notes) obscures such evidence. The vivid appearance of the Buccleuch drawing[18] and its parchment support suggest that it may have served in the workshop as either a model for portraits of Luther or as a ricordo. If the former, then the Metropolitan portrait has followed this model very closely indeed.

[1] See especially Martin Warnke (1984) on this subject. See also Hess and Mack 2010.

[2] Warnke 1984, p. 62; Karin Kolb in Chemnitz 2005 – 6, pp. 474 – 79, ill. ([DE_SKD_GG1918_FR314-315], [DE_SKD_GG1919_FR314-315]). Other examples of these pendants are found in the State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg (nos. ГЭ8600 and ГЭ8601); the Uffizi Gallery, Florence (nos. 472, 512); and the Fürstenbergsammlungen Donaueschingen (nos. 727, 728). There are also various single, unmatched portraits of these two sitters (curatorial files, Department of European Paintings, MMA).

[3] No known pendant of the Melanchthon portrait can be definitively linked to the Museum’s Luther.

[4] See Gemäldegalerie (Berlin) 1986, nos. 617, 619 ([DE_smbGG_617_FR314-315F], [DE_smbGG_617_FR314-315F]). This particular pose and close-up view of Luther enjoyed even wider circulation through the prints of Heinrich Aldegrever and Hans Brosamer. Aldegrever joined his Luther with a portrait of Melanchthon (Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nuremberg [nos. K305, K306]), and Brosamer joined his with a portrait of Katharina von Bora (Hollstein 1954 – , vol. 4 [1957], pp. 260 – 61, nos. 596, 597).

[5] Löcher 1995, p. 371.

[6] Löcher 1997, p. 149.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Löcher 1995, p. 371.

[9] Kokoska 1995a, p. 9.

[10] Kokoska 1995b, p. 16.

[11] Löcher 1995, p. 371. See also John Oliver Hand, Catherine A. Metzger, and Ron Spronk in Washington and Antwerp 2006 – 7, pp. 116 – 21, no. 16.

[12] Löcher 1995, p. 371.

[13] Scribner 1981, pp. 247 – 48.

[14] I am grateful to Joshua Waterman for his research and discussions with me regarding these interpretations.

[15] Max J. Friedländer, unpublished opinion, Berlin, March 6, 1927 (on verso of photograph; copy in curatorial files, Department of European Paintings, MMA).

[16] Friedländer and J. Rosenberg 1932, p. 75, no. 252k; Kuhn 1936, pp. 44, no. 143; Friedländer and J. Rosenberg 1978, pp. 130 – 31, no. 314F; Baetjer 1980, vol. 1, p. 37; Baetjer 1995, p. 223.

[17] The Cranach insignia on the Christie’s version is somewhat suspect. The serpent’s wings appear to be lowered, but they still show little spikes pointing upward at the top ridge of the wing. This is either an uncommon raised-wing serpent, which would be typical of the 1532 date, or an unusual lowered-wing serpent, which would raise doubt about a dating before 1537, when the workshop changed from the raised-to the lowered-wing sign.

[18] Schade 1980, p. 53.

[Ainsworth / Waterman 2013, p. 85, No. 18]