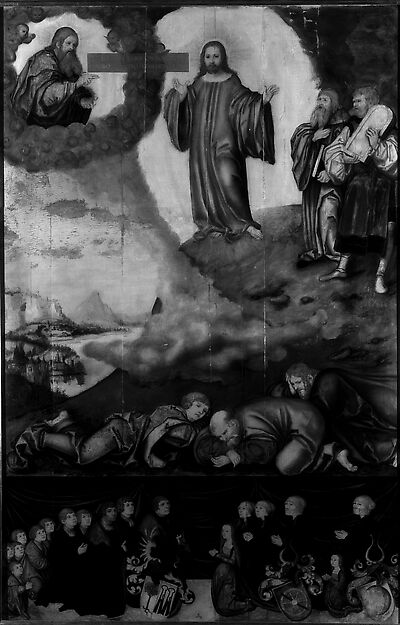

Johann Wolfgang Goethe described this painting in 1815: ‚The painting is a moment, a cast of the thoughts, perhaps the ultimate ingenious moment in Cranach’s life.’ (“Das Bild ist ein Moment, ein Guss des Gedankens, vielleicht der höchste gunstreichste Augenblick in Cranachs Leben"). Contrary to this effusive appraisal it has been rather neglected in previous Cranach research. The only issue discussed, as is so often the case, was the question of the degree of authorship by Cranach. However, since the publication of Friedländer/Rosenberg this is no longer called into question.

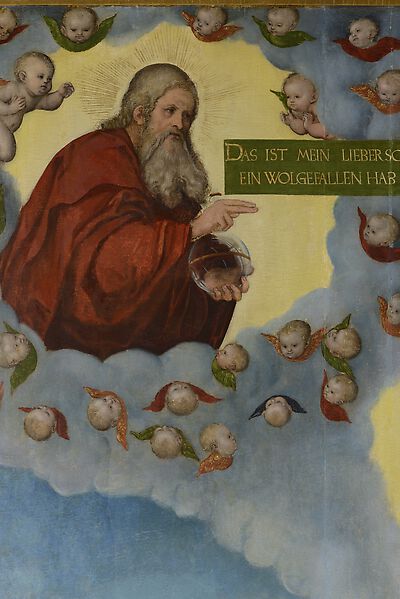

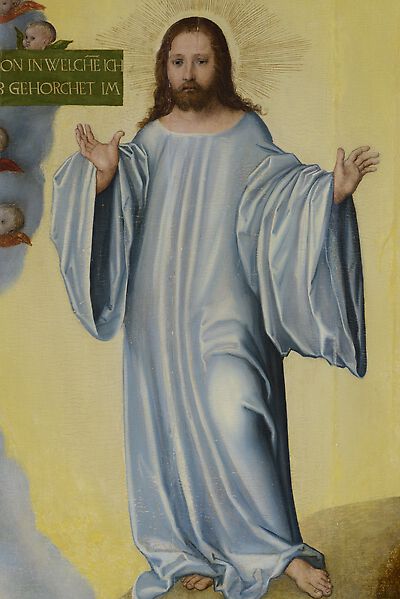

It depicts the Transfiguration of Christ as recounted by the Evangelists Matthew (17.1-13), Mark (9.2-13) and Luke (9.28-36): Christ took the apostles Peter, John and James with him in to the mountain. There his robe became ‘white like the light’, and the prophets Moses and Elijah appeared and spoke with him. The voice of God resounded from the heavens, his words: ‚This is my own dear Son, with whom I am pleased - listen to him!‘, which are incorporated into the inscription can be found in the Gospel according to Matthew. All three Evangelists refer only to the voice of God, which came from a cloud, and not to his manifestation. In contrast God the Father is depicted in the painting, but is only visible to the viewer and is hidden from the apostles by the clouds. The apostles, terrified by the apparition, fall to the ground. Two of them appear to sleep, which is only recounted in the Gospel according to Luke.

The Transfiguration of Christ is interpreted as the pre-figuration of the Ascension. By giving expression to the belief in the resurrection and eternal life the subject is suited to the theme of death associated with an epitaph.

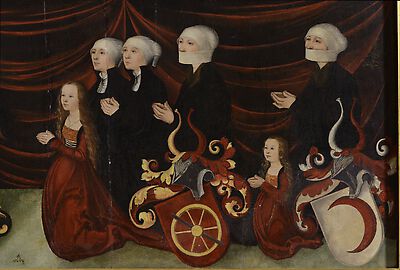

The clouds divide the scene into four levels of reality: God the Father, Christ and the prophets, the apostles and finally the sunlit landscape are separated from each other. The lower zone with the donor family is added as a fifth level of ‘reality’. There is no prototype in art history corresponding to Cranach‘s solution for the depiction of the Transfiguration. Indeed Cranach appears to have been commissioned only on this one occasion with a depiction of the Transfiguration, which he in addition executed as an unusually large format work. The Leipzig council member and merchant Ulrich Lintacher is depicted as the head of the donor family. There is no doubt about his identity; the family coat-of-arms and an entry by Salomon Stepner (No. 473) are in this case unequivocal: Stepner mentions an epitaph for Lintacher (d. 1525) with a painting of the transfiguration in the Nikolaikirche where it hung above the students’ chancel.

Lintacher came from Nuremberg to Leipzig, he aquired citizenship in 1499 and invested among others with high profit in mining. He became a council member in 1515 and from 1522 assumed the position of Council Architect (Amt des Ratsbaumeisters). During his term of office the late Gothic conversion of the Nikolaikirche was carried out. He was also one of the ‘Church Fathers’.

Lintacher owned a house in the market square and one in Reichstraße. Through the inheritance of his second wife Brigitta, whose maiden name was Wilde, the family acquired a further house in the Grimmaischen Straße.

On the basis of written sources pertaining to the family of Ulrich Lintacher most of the other family members represented here could be identified:

Opposite Ulrich Lintacher kneel four women, whose clothing and bonnets identify them as married, two of them also wear black bands. The last two are his wives. His first wife, Veronika, died in 1518. Then he married Brigitta Wilde, daughter of the Mayor Johann Wilde. She was still alive when Lintacher died in 1525 and remarried soon after.

The two married women without black bands are probable the two daughters from his first marriage, who were already married in 1525: Ursula, married to Benedict Beringershain/Belgershain, later mayor of Leipzig, and Anna, married to Moritz Buchner the Younger. The two daughter clothed as maidens in red are Elizabeth from the first marriage and a daughter from the second, whose forename is not recorded in the sources. Behind the father kneel the two elder sons Christoph and Ulrich from the first marriage, shown wearing coats with fur collars distinguishing them as citizens in office and dignities, behind them, slightly younger and still without a fur collar Wolfgang and Johannes, sons from the second marriage.

The sources reveal nothing about the six younger children in red on the left side of the painting, they may already represent the generation of grandchildren.

The Lintacher family was the first family from Leipzig to commission an epitaph from Lucas Cranach, at that time an already widely celebrated artist. In 1525 there were already two paintings by him in the Nikolaikirche, the panel showing the ‘Holy Trinity’ from 1515 and the painting ‚The Dying Man’ about 1518 (both now in the Museum der bildenden Künste Leipzig). Cranach was at least equally sought after for his skill in the field of portraiture, which he had developed to an unparalleled level in the region of central Germany. In Leipzig influential figures like Moritz Buchner (1518) and Georg von Wiedebach (1524) had already been portrayed by him with their wives. The Lintacher family was associated with both on either business or family terms and it is possible that Cranach was assigned indirectly through them. Cranach’s portraiture considerably upgrades the representation of the donor family on the epitaph compared to well-known examples from about 1500. Thus not only the requirements of a representation befitting the status of the family is served, but also their confession of faith, which is visible to all church visitors.

[Ulrike Dura, Cat. Leipzig 2006, 123-124]