- Attributions

-

Lucas Cranach the Younger

Lucas Cranach the Elder

Attributions

| Lucas Cranach the Younger | [The Metropolitan Museum of Art, revised 2011] |

| Lucas Cranach the Elder | [Kuhn, Exhib. Cat. Cambridge, Mass. 1936, 36, No. 83] |

- Production dates

- about 1545

about 1520

Production dates

| about 1545 | [The Metropolitan Museum of Art, revised 2011] |

| about 1520 | [Kuhn1936, 36, no. 83] |

| 1545 | [Bauman, Cat. New York 1984, 101-4, No. 37] |

- Dimensions

- Dimensions of support: 17.1 x 21.9 x c. 0.15 cm

Dimensions

Dimensions of support: 17.1 x 21.9 x c. 0.15 cm

Dimensions of painted surface: 15.2 x 20.6 cm

[The Metropolitan Museum of Art, revised 2011]

- Signature / Dating

Artist's insignia at the top right: winged serpent with dropped wings

Signature / Dating

Artist's insignia at the top right: winged serpent with dropped wings

- Inscriptions and Labels

- top edge:

'LASSET DIE KINDLIN ZV MIR KOMEN.VND WERET INEN NICHT.DENN SOLCHER IST DAS REICH GOTTES. ~ MARCVS.X. ~'

(Suffer …

Inscriptions and Labels

Inscriptions, Badges:

- top edge:

'LASSET DIE KINDLIN ZV MIR KOMEN.VND WERET INEN NICHT.DENN SOLCHER IST DAS REICH GOTTES. ~ MARCVS.X. ~'

(Suffer the little children to come unto me, and forbid them not: for of such is the kingdom of God [Mark 10:14].)

Stamps, Seals, Labels:

Reverse of the cradle:

round red-bordered label with pinked edges, handwritten inscription in black ink: D626

in white chalk '11'

[The Metropolitan Museum of Art, revised 2011]

in red paint: '1982.60.36'

in graphite, on masking tape: '11'

[Cat. New York 2013, 98, No. 22B]

- Owner

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

- Repository

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

- Location

- New York

- CDA ID

- US_MMANY_1982-60-36

- FR (1978) Nr.

- FR-none

- Persistent Link

- https://lucascranach.org/en/US_MMANY_1982-60-36/

- top edge:

Provenance

- 1920 recorded in the Ehrich Galleries, New York

- R. Langton Douglas, London

- Agnew, London

- until 1936 in the collection of R. Ederheimer, New York

- from 1936 in the collection of Henry Schniewind, New York

- Mrs. Arthur Corwin, Greenwich, Conn.

- by 1945-55 sold to Newhouse

- 1955 acquired by Linsky from the Newhouse Galleries, New York

- 1955- 1980 Mr. and Mrs. Jack Linsky, New York

- 1980-1982 Mrs. Jack (Belle) Linsky, New York

[The Metropolitan Museum of Art, revised 2011]

Exhibitions

Cambridge, Mass. 1936, No. 9

New York 1960, No. 8

Literature

| Reference on page | Catalogue Number | Figure / Plate | |||||||||||||

| Frank 2018 | 136, 137 | Fig. 57 | |||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

| Hoppe-Harnoncourt 2015 | 163, Fn. 52, 53 | ||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

| Waterman 2015 | 284, Fn. 19 - 286 | Fig. 4 | |||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

| Cat. New York 2013 | 98-102 | No. 22B | |||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

| Exhib. Cat. Prague 2005 | 98 (English version 39) | under no. 21 | |||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

| Cat. New York 1995 | 221 | Fig. | |||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

| Cat. New York 1984 | 101-104 | No. 37 | |||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

| Metropolitan Museum 1984 | 57-58 | Fig. | |||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

| Andersson 1981 | 59 | No. 57 | |||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

| Exhib. Cat. Cambridge, Mass. 1936 | 36 | 083 | |||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

| Kuhn 1936 | 36 | 083 | |||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

Research History / Discussion

'This picture and its companion ("Christ and the Adulteress," MMA 1982.60.35) were confused by Bauman [see Ref. 1984] with two works in nineteenth-century catalogues of the Herzogliches Museum, Gotha (1858, nos. 102–3; 1890, nos. 364–65), but those works remain in the Schlossmuseum Gotha (inv. nos. SG6, SG11) and are considered copies after the MMA pictures.

Friedländer and Rosenberg ("The Paintings of Lucas Cranach," rev. ed., Ithaca, N.Y., 1978) list fourteen versions of this subject by Cranach and his workshop (nos. 217, 217A–C, 362, 362A–H, 363), but include neither the MMA nor the Gotha panels. Dieter Koepplin ("Lukas Cranach: Gemälde, Zeichnungen, Druckgraphik," vol. 2, Basel, 1976, p. 518, no. 367) adds a fifteenth version.'

[http://www.metmuseum.org/works_of_art/collection_database/european_paintings/christ_blessing_the_children_lucas_cranach_the_elder/objectview.aspx?page=1&sort=6&sortdir=asc&keyword=cranach&fp=1&dd1=11&dd2=0&vw=1&collID=11&oID=110000469&vT=1&hi=0&ov=0] (accessed: 09.05.2011)

These two small paintings depict the New Testament stories of Christ and the Adulteress and Christ Blessing the Children. Although both subjects were frequently treated by the Cranach workshop, their pairing as pendants was unprecedented.

The story of Christ and the Adulteress is told in the Gospel of John (8:2 – 11). A group of scribes and Pharisees brought before Jesus a woman accused of adultery, which in Mosaic law was punishable by death. They asked for his verdict, suspecting that he might contradict the law and thereby incriminate himself. His response, “He that is without sin among you, let him first cast a stone at her” (John 8:7), exposed the accusers’ self-righteousness.

The painting sets the three-quarter-length figures before an abstract black background. The armored men are an embellishment of the biblical account; they serve to contrast the violent intentions of the accusers with Christ’s message of forgiveness, while also adding variety to the scene. Also in the painting are two figures with typical features of the apostles Peter (balding, with a short gray beard) and Paul (with a long brown beard), who are not part of the narrative. The same two disciples appear in the companion panel and thus help to unify the compositions.

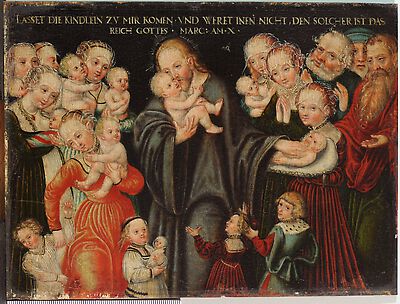

The story of Christ Blessing the Children appears in the Gospels of Matthew (19:13 – 15), Mark (10:13 – 16), and Luke (18:15 – 17). When children were brought to Jesus for blessing, his disciples raised objections.

Countering their complaints, he said, “Suffer the little children to come unto me, and forbid them not: for of such is the kingdom of God” (Mark 10:14; and similarly in Matthew 19:14 and Luke 18:16).

This painting uses the same compositional scheme as its pendant. The motifs of Christ lifting one child to kiss its cheek and laying a hand on another derive from Mark 10:16, which relates that Christ “took them up in his arms, put his hands upon them, and blessed them.”[1] Four older children along the bottom edge show various states of attention: a boy on a hobbyhorse turns away, distracted, while being pulled along by his mother; a girl in pigtails, holding a doll wrapped in swaddling clothes, waits patiently before Christ; and a still older girl and boy dressed in lavish courtly costume stand to the other side of Christ, she with arms raised in excitement and he apparently trying to prevent her from rushing forward. The apostles Peter and Paul register their surprise with upturned hands.

Of the two subjects, Christ and the Adulteress appeared earlier in the repertoire of the Cranach workshop. Lucas Cranach the Elder’s first painted treatment of the theme, the panel of about 1520 in the Fränkische Galerie, Kronach,[2] established a compositional standard— horizontal format, friezelike arrangement of figures, and black background — that endured for decades in numerous examples, including the Metropolitan’s panel. The horizontal format and half-length figures of the panel in Kronach seem to rely on Venetian prototypes, such as the Christ and the Adulteress by Marco Marziale of about 1505 (Bonnefantenmuseum, Maastricht).[3] Whereas Dieter Koepplin speculated that Cranach might have encountered the compositional scheme in a northern Italian painting imported to Saxony, Sabine Engel proposed that the medium of transmission could have been a drawing after a Venetian composition brought to Wittenberg by Jacopo de’ Barbari.[4] Cranach’s iconographic innovation, also with respect to earlier German examples, was to have Jesus take the woman’s arm, which emphasizes his protective mercy.[5]

Before the sixteenth century, the theme of Christ Blessing the Children appears to have been confined to manuscript illumination.

Cranach is credited with introducing it to panel painting.[6] He first treated the subject in the mid-to late 1530s; the earliest dated examples are the panels of 1538 in the Hamburger Kunsthalle and the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden.[7] It was an extraordinarily popular product of the Cranach workshop; some twenty-five versions are currently known, and Elector Johann Friedrich I, the Magnanimous (r. 1532 – 47), ordered at least three.[8]

Evidently the Metropolitan’s panels are the only examples to have been designed as pendants. Although in their modern history they were united only in the 1930s, the matching dimensions, similar handling and execution, and close resemblance of the Christ, Peter, and Paul figures in both all strongly suggest that they originally were a pair. Another indication that they were meant to be displayed together is the inscription on Christ Blessing the Children. As Christiane Andersson noted, most depictions of the theme display not Christ’s spoken words, “Suffer the little children to come unto me . . . ,” but instead the narrative verse (Mark 10:13), “And they brought young children to him, that he should touch them.”[9] The choice here of the less common “speaking” verse creates continuity with the inscription on the companion panel, in which Christ also speaks (“He that is without sin among you . . .”). The existence of a pair of sixteenth-century copies in the Schlossmuseum, Schloss Friedenstein, Gotha (figs. 80, 81), is further evidence that the pendant arrangement is original.[10] Attachment as a folding diptych would be unusual for the horizontal format; probably the works were simply displayed side by side in whichever arrangement the owner preferred. The small size indicates that the pair was made for private viewing, and the courtly costume of the two children at the bottom center of Christ Blessing the Children suggests princely patronage.

The pairing of the subjects emphasizes the notion of the free dispensation of divine grace.[11] The stories were discussed in those terms by Martin Luther and his followers, who also used them to demonstrate the break with Mosaic law initiated by the Gospel of Christ. Concerning Christ and the Adulteress, Luther’s 1531 sermon on John 8 states, The story is related to show the clear distinction between the Law and the Gospel, or between the kingdom of Christ and that of the world. . . . In Christ’s realm no punishment is to be found, but only mercy and forgiveness of sins, whereas in the realm of Moses and the world there is no forgiveness of sins, but only wrath and punishment.[12]

In the same sermon, Luther preached, “[S]ee how sweet . . . the grace of God is, the grace which is offered to us in the Gospel. This is the absolution which the adulteress receives here from the Lord Christ.”[13] Similarly, in an exegesis of Psalm 29 published in 1542, Johannes Bugenhagen, a close confidant of Luther, wrote of the story of Christ Blessing the Children, Here we have a decree of grace, most certainly: “Suffer the little children to come unto me, etc.” . . . This is not God’s secret judgment and grim wrath, but rather God’s gracious promise, that the kingdom of heaven belongs to our children, and so they are brought to Christ.[14]

Although those remarks were made in defense of the baptism of infants, they also indicate that Lutherans understood the story more broadly, much like Christ and the Adulteress, as an example of God’s free gift of grace to humanity. The more specific interpretation of Cranach’s depictions of Christ Blessing the Children as propaganda against the Anabaptist opposition to infant baptism — a reading first advanced by Christine Kibish — would seem not to apply to the Museum’s picture.[15] The small size and the pairing with Christ and the Adulteress are at odds with any use as religious propaganda.

When displayed together, the Metropolitan’s pendants were much rather meant to prompt the pious viewer to meditate on the common theme of divine grace.

In the catalogue of the Linsky Collection, Guy Bauman dated the Museum’s pair in the mid-1540s and noted stylistic similarities with works attributed to Lucas Cranach the Younger, especially the 1549 Saint John the Baptist Preaching in the Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum, Braunschweig.[16] Despite the disparity in scale (the latter panel is about eight times larger than those in New York), the figures in Braunschweig and New York are of a similar type and share an exaggerated redness in the cheeks and noses, which frequently conveys a doll-like appearance. Comparable features are found in other large-scale works of the mid-to late 1540s that are attributed to Lucas the Younger, such as the 1545 Elijah and the Priests of Baal in the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden, and the 1549 Conversion of Saul in the Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nuremberg.[17] In both, the rosy tones in the faces are especially pronounced, and in the panel in Nuremberg, the representation of highlights on armor is particularly close to that of the armored figures in Christ and the Adulteress.

The Metropolitan’s pendants align stylistically with several other small panels produced in the mid-to late 1540s.[18] These include two pictures dated 1547 (Saint Paul; private collection)[19] and 1549 (The Fall of Man; fig. 82),[20] and several undated paintings of comparable appearance,[21] one of which is the Museum’s Nymph of the Spring (cat. 21). In addition to the strong rosiness in the flesh tones and dollish quality of the figures that they have in common with the large panels mentioned above, they also share certain idiosyncrasies of execution, such as large irises, prominent black lines used to indicate the shadow beneath the upper eyelid, and brown outlines around the hands and fingers. In reference to a selection of the small panels, Dieter Koepplin wrote of a “miniaturistic style, independent of the father’s manner” that Lucas Cranach the Younger appears to have developed in the late 1540s.[22]

The Fall of Man is particularly relevant to the question of authorship because of a drawing (in the same museum) that records the composition and bears an old inscription in Latin attributing the painting expressly to Lucas Cranach the Younger.[23] While not necessarily proof of the younger Cranach’s authorship,[24] the inscription at least reflects an old tradition — possibly reaching back to the sixteenth century — of associating the painting with him, and thus provides further evidence for attributing pictures of similar style to Lucas Cranach the Younger. The emergence of a distinct manner in both large-and small-scale paintings in the mid-1540s points to a growing autonomy of Lucas the Younger within the workshop at that time and suggests that certain workshop assistants may have trained more intensely under him than under his father.[25]

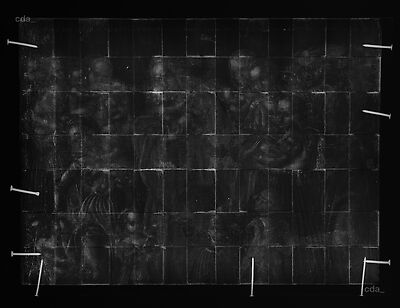

Although the Museum’s panels are nearly identical in handling and execution, small differences in quality suggest that greater care was lavished upon Christ and the Adulteress. Generally, the figures in Christ Blessing the Children are somewhat flatter in appearance. For example, in Christ and the Adulteress the head and facial features of Saint Peter are convincingly volumetric, but in Christ Blessing the Children the same head, turned in the other direction, is more planar in overall form and more summary in execution. The same difference is apparent in the X-radiographs, which reveal a clear buildup of lead white at the cheek, forehead, and brow of Peter in Christ and the Adulteress and much less distinct forms in the corresponding head in Christ Blessing the Children (figs. 83, 84). These differences suggest that, while both works can be attributed to Lucas Cranach the Younger, the participation of a different hand in the completion of Christ Blessing the Children is possible.

[1] The accounts in Matthew and Luke refer to Christ touching but not actually holding the children.

[2] On loan from the Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Munich (Friedländer and J. Rosenberg 1978, p. 95, no. 129, ill.; Michael Henker in Kronach and Leipzig 1994, p. 333, no. 155, ill.; Sabine Engel in Brussels and Paris 2010 – 11, pp. 228 – 29, no. 145, ill.).

The original background of the Kronach picture is covered by an architectural backdrop added during the seventeenth century. For other examples of the subject, see Friedländer and J. Rosenberg 1978, pp. 111, 141 – 42, nos. 216, 364, 364A – G, 365, ill. (nos. 216, 364, 365).

[3] Ringbom 1984, pp. 190 – 91, fig. 158; Engel in Brussels and Paris 2010 – 11, p. 228, no. 144, ill.

[4] Koepplin in Basel 1974, vol. 2, p. 516, under no. 364; Engel in Brussels and Paris 2010 – 11, p. 228, under no. 145. Alternatively, Helga Hoffmann suggested that Cranach, relying on the example of late Gothic predellas with half-length figures, could have arrived independently at this format (H. Hoffmann 1990, p. 83).

[5] See, for example, the depiction on Michael Pacher’s Altarpiece of Saint Wolfgang (1471 – 81; Kahsnitz 2005, pl. 37) and the early woodcuts and engravings cited by Koepplin (in Basel 1974, vol. 2, p. 516, under no. 365), in which Christ and the adulteress stand opposite one another.

[6] See Koepplin in Basel 1974, p. 517, under no. 366. Kibish 1955, pp. 196 – 97, cites examples in manuscripts from the eleventh through the fourteenth century.

[7] Friedländer and J. Rosenberg 1978, p. 141, no. 362 (Hamburg), ill., no. 362A (Dresden); respectively, Sitt 2007, pp. 98 – 99, ill.; Karin Kolb in Chemnitz 2005 – 6, pp. 302 – 11, no. 17, ill. These may be preceded by a few years by the undated picture in the Städel Museum, Frankfurt (ca. 1535 – 40; Friedländer and J. Rosenberg 1978, p. 112, no. 217A; Bodo Brinkmann in Brinkmann and Kemperdick 2005, pp. 226 – 34, ill.)

[8] For the current tally, see Kolb in Chemnitz 2005 – 6, p. 308. On Johann Friedrich’s orders, documented in 1539, 1543, and 1550, see Friedländer and J. Rosenberg 1978, p. 112, under no. 217.

[9] Andersson 1981, p. 53.

[10] Werner Schade in Gotha 1994, pp. 53 – 54, nos. 1.22, 1.23, ill. The recorded provenance of the Gotha pair reaches back to 1721. Guy Bauman (in Metropolitan Museum 1984a, pp. 103 – 4) knew the Gotha panels only from an old description and mistakenly considered them to be the ones now in New York.

[11] The common theme has not gone unrecognized: Werner Schade (1974, p. 74) characterized both subjects as “examples of the Lutheran doctrine of election by grace” (Beispiele evangelischer Gnadenwahl).

[12] Cited in Christensen 1979, p. 132.

[13] Cited in ibid., p. 133. See also Preuss 1926, pp. 181 – 82; Andersson 1981, pp. 51 – 53.

[14] Johannes Bugenhagen, Der XXIX. Psalm ausgelegt (Wittenberg, 1542), fol. E1r, “Hie haben wir ein gnaden vrteil, sicher vnd gewiss, Lasset die Kindlein zu mir komen etc. . . . Das heisset nicht Gottes heimliches gericht vnd finster wahn, sondern Gottes gnedige zusage, das vnser Kinder das Himelreich eigen ist, so Christo werden zugebracht.”

[15] See Kibish 1955, pp. 199 – 200. Scholarship since Kibish tends to concede the possible anti-Anabaptist sentiment behind the initial appearance of the theme while seeking broader explanations for its later proliferation, such as the appreciation of family and parenting, the value placed on childlike faith in God, and the emphasis on divine grace found in other Lutheran writings (see Koepplin in Basel 1974, vol. 2, p. 518, under no. 366; Christensen 1979, p. 136; Andersson 1981, p. 55; Gottfried Seebass in Nuremberg 1983a, p. 270, under no. 349; Peter-Klaus Schuster in Hamburg 1983 – 84, p. 241, under no. 114; B.-J. Noble 1998, pp. 243 – 44; Brinkmann in Brinkmann and Kemperdick 2005, pp. 230 – 32; Kolb in Chemnitz 2005 – 6, pp. 310 – 11 — all preceded by the seminal discussion in Preuss 1926, pp. 181 – 82).

[16] Bauman in Metropolitan Museum 1984a, p. 104. Charles L. Kuhn (1936, p. 36, nos. 82, 83) attributed them to Lucas Cranach the Elder and proposed a date of about 1520. For the Braunschweig picture, see Schade 1974, pl. 212.

[17] Kolb in Chemnitz 2005 – 6, pp. 236 – 45, no. 7, ill. (Dresden); Friedländer and J. Rosenberg 1978, pp. 156 – 57, no. 433, ill.; Löcher 1997, pp. 164 – 66, ill. (Nuremberg).

[18] The panel sizes are generally consistent with the standard Cranach panel format A (18.5 – 22.5 × 14 – 16 cm), according to the categorization in Heydenreich 2007b, p. 43.

[19] Christie’s, New York, sale cat., January 30, 2013, no. 112, ill.

[20] Friedländer and J. Rosenberg 1978, p. 156, no. 432, ill.; see also Scharf 1929; Koepplin in Basel 1974, vol. 2, p. 510, under no. 355.

[21] The Adoration of the Shepherds (private collection; see Christie’s, Monaco, sale cat., June 22, 1991, no. 114, ill.; Galerie Fischer, Lucerne, sale cat., December 2, 1993, no. 2155, ill.); The Baptism of Christ (Cleveland Museum of Art; see Jean Kubota Cassill in Cleveland Museum of Art 1982, p. 165, no. 67, fig. 67); Saint John the Baptist and Virgin of the Apocalypse (Museo Poldi Pezzoli, Milan; see Koepplin in Basel 1974, vol. 2, p. 510, under no. 355; Schade in Hamburg 2003, p. 178, no. 60a – b, ill.); and Law and Gospel (Lutherhaus, Wittenberg; see Koepplin in Basel 1974, vol. 2, p. 510, no. 355, fig. 275; Strehle 2001, p. 94, ill.; Martin Treu in Joestel 2008, p. 134, ill. p. 135); the latter, at 19 × 25.5 cm, is somewhat larger than the rest.

[22] Koepplin in Basel 1974, vol. 2, p. 510, under no. 355.

[23] Pen, black and brown ink, and black wash on laid paper; image: 22.9 × 17.1 cm; Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, The Edith A. and Percy S. Straus Collection, no. 44.547. The inscription reads, “Pinxit haec Lucas, Lucae Cranachii filius, Ducum Saxoniae quodam [quidam?] picttor” (Lucas, son of Lucas Cranach, a certain painter to the dukes of Saxony, painted this).

[24] But Scharf 1929, p. 698, and Friedländer and J. Rosenberg 1978, p. 156, no. 432, take the inscription as proof.

[25] This notwithstanding the reluctance that Lucas the Younger expressed in 1550 to take a commission in the absence of his father, on which see Erichsen 1997, pp. 49 – 50; Heydenreich 2007b, pp. 294 – 95.

[Waterman, Cat. New York 2013, 98, 100-102, 294, 295, No. 22B]