According to the oldest known version of the story, the Passio acaunensium martyrum (The Passion of the Martyrs of Agaunum), dating to about 450 and based on the writings of Eucherius, bishop of Lyons, Maurice commanded a Roman legion in Thebes, which was an early Christian territory.[1] When he and his African soldiers were ordered by Emperor Maximian to persecute the Christians in Gaul, they refused and were martyred near Agaunum (present-day Saint-Maurice-en-Valais) on September 22 in 280 or 300.[2] The cult of Saint Maurice, most widespread in the Late Middle Ages, was first associated with the royal house of Burgundy and thereafter with Saxon and Ottonian kings.[3] One of the main centers for the veneration of Saint Maurice was the archdiocese of Magdeburg, particularly the eastern German city of Halle, where as early as 1184, an Augustinian convent and monastic school were founded and dedicated to him.[4] From 1484 to 1503, during the rule of Archbishop Ernst of Wettin, the Moritzburg, the seat of the ruler, was built in Halle.[5] Ernst was among the most notable art patrons of the period, surpassed only by his successor, Albrecht of Brandenburg.

The youngest son of a family of Wettin and Habsburg descent, Albrecht was elected archbishop of Magdeburg and bishop of Halberstadt in 1513. He quickly rose in the church hierarchy, and in 1518 he was made cardinal and succeeded as high chancellor primate, becoming one of the most influential and wealthy individuals within the Holy Roman Empire. Albrecht made the Moritzburg his main residence and endowed the Dominican church nearby with special privileges upon its dedication in 1523 as the Neues Stift (New Foundation).[6] This church, with Saints Maurice, Erasmus, and Mary Magdalen as patrons, became Albrecht’s showplace. He called upon Matthias Grünewald, his court painter from 1516 to 1526, to produce a painting representing a conversation between Saint Maurice and himself, in the guise of Saint Erasmus (Alte Pinakothek, Munich).

From 1520 to 1525, Albrecht commissioned sixteen altarpieces from Lucas Cranach and his workshop; these exist today only in a fragmentary state, although their original placement is known from a detailed inventory.[7]

The Neues Stift also housed the most important collection of relics in northern Europe, which had been initiated by Ernst of Wettin. Its approximately 8,200 objects comprised not only modest-appearing relics, associated with the calendar of saints celebrated throughout the liturgical year,[8] but also far more extraordinary reliquaries. The first inventory of the collection appeared in 1520 in a printed version that included an engraved portrait of Cardinal Albrecht by Dürer as well as a title-page woodcut by Wolf Traut showing Albrecht and Ernst of Wettin flanking the Neues Stift, with its three patron saints surrounded by angels in the heavens above.[9]

In 1526 – 27 a second inventory, called the Liber ostensionis and generally known as the Hallesches Heiltumsbuch (Halle Book of Relics),[10] was produced for Albrecht’s personal use. Probably illustrated by a Cranach pupil (possibly Simon Franck),[11] it described 353 reliquaries, all but three of which were illustrated. Although few of these unique reliquaries survive, the drawings testify to their superior craftsmanship and luxurious materials.

It is in the context of Albrecht’s Neues Stift, his patronage of the arts, his commissions from Cranach and his workshop, and above all his collection of relics and reliquaries that the Museum’s recently resurfaced painting of Saint Maurice must be understood.[12] Approximately seventeen of the images in the Hallesches Heiltumsbuch depict the saint and relics associated with him. The most important of these, and indeed the most important that Albrecht owned, was a lifesize silver reliquary statue produced about 1520 – 21, the designer of which remains unknown (fig. 63).[13] This work was the prototype both for the Metropolitan’s painting and for another that forms the left wing of the 1529 polyptych displayed on the main altar of the Marktkirche in Halle (attributed to Simon Franck; see fig. 65).[14] Surrounded by thirteen main lamps and seven subsidiary ones, the reliquary of Saint Maurice stood on a red brocade pillow beneath its own baldachin before the high altar in the Neues Stift. Its silver armor was partially gilded and further embellished with precious jewels and pearls. The head was made of wood or metal, and the hat of gold brocade with ostrich feathers. Dangling from the tips of the feathers were gold and jeweled teardrop-shaped ornaments that moved as the air circulated. According to the description in the Hallesches Heiltumsbuch, numerous relics were housed inside.[15]

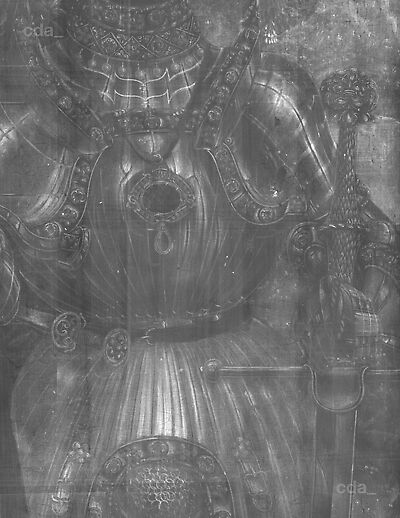

In the reliquary statue and the two related paintings, Maurice is depicted as the patron saint of the empire and not, as had been more common from the twelfth century on, as the patron of the Magdeburg archdiocese. The armor worn by both the statue and the figure in the Museum’s painting clearly refers to Emperor Charles V. The symbol of the Burgundian Golden Fleece is attached to the cuirass, the Saint Andrew’s Cross appears between sparking flint stones on the pauldrons, and the banner bears the imperial eagle as well as Charles’s emblems. The sword denotes Maurice’s role as a soldier-saint as well as the instrument of his decapitation. It may also represent the gilded-silver ceremonial sword presented to Emperor Maximilian I by Pope Leo and passed on to Albrecht at his investiture as cardinal.[16] Installed in a place of honor near the high altar and bearing the insignia of Charles V, the reliquary thus symbolized the close relationship between the emperor and Albrecht.[17]

The Museum’s painting follows the Saint Maurice illumination of the full-length reliquary statue in the Hallesches Heiltumsbuch quite closely while masterfully adjusting the figure and his massive armor to fit into the narrow format of a side wing of an altarpiece. Some of the altarpieces executed by the Cranach workshop for Albrecht were multipanel ensembles, occasionally with more than one opening. Various surviving models, both drawn and assembled, show that a closed altarpiece could comprise four very narrow panels, with two each for the right and left wings.[18] Since Maurice faces to the right here, our panel probably formed the inside left wing of such an altarpiece, the remainder of which has not been identified and may no longer exist.

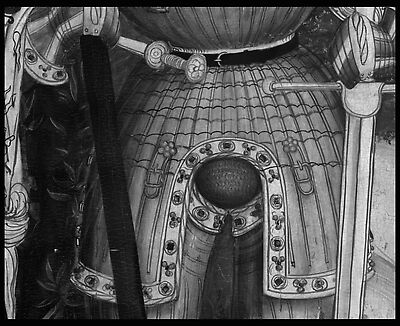

The armor in the Museum’s painting is a type known as Feldküriss (field armor) and dates from about 1510 – 20. Rendered in great detail and based on known examples, it is generally quite similar to contemporary German armor in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum and the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna.[19] Even the fanciful red beret with feathers derives from actual costumes of the time. A surviving example in the Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nuremberg, that once belonged to Christoph Kress von Kressenstein retains the same dangling gold ornaments as on Saint Maurice’s beret.[20] The armor of the reliquary statue (and by association that in the Metropolitan’s painting) is thought to have been based on that worn by Charles V for his coronation in Aachen on October 22, 1520, which was subsequently given to Cardinal Albrecht as a present; however, documentary proof of this theory is lacking.[21]

Some have suggested that it reproduces the armor that Albrecht gave to Charles for that occasion; others propose that it was owned by Maximilian I, who offered it as a coronation gift to Charles.[22]

A fitted, full-plate cavalry armor, it featured a harness and fluted jupon, with vertical and horizontal ridges and a narrow girdle. Cantilevered pauldrons encased the shoulders, while the arms and legs were clothed in metal defenses.

The authorship of Saint Maurice has been addressed infrequently, as the painting has not been available for firsthand study. The 1946 Parke-Bernet auction catalogue attributed the painting to Lucas Cranach the Elder and the similar example in the Marktkirche in Halle to the workshop.[23] On the basis of black-and-white photographs only, Gude Suckale-Redlefsen ascribed the Metropolitan’s painting either to an immediate collaborator of Cranach or to the master himself.[24] Andreas Tacke identified the artist as one of those who painted the Halle picture cycle in the Neues Stift.[25] In determining the attribution of our painting, we must consider the situation of the Cranach workshop at the time it was made. The sixteen altarpieces that Albrecht commissioned from Cranach between1520 and 1525 comprised more than 142 separate panels. Cranach and his shop were accustomed to handling large commissions and had a reputation for completing them on schedule. An epithet used in praise of Cranach — pictor celerrimus (the fastest painter) — may still be read on his tomb in the city church in Weimar. Indeed, Cranach developed a style of painting that depended on shortcut solutions and an extensive use of easily copied patterns and rote methods of producing decorative detail that could be successfully replicated by assistants. By the 1520s, the artist had adopted an increasingly streamlined painting technique that permitted rapid execution by both himself and his assistants. Recent technical studies have yielded important new information about the painting techniques of the workshop, but it is not always easy to distinguish Cranach’s own hand from that of his assistants.[26] Ingo Sandner considered that Cranach was generally involved in various ways at the underdrawing stage.[27] The difficulty of identifying individual hands in the painted layers remains, however, because the workshop achieved its major goal so well — producing a recognizable style at a consistent level of quality.

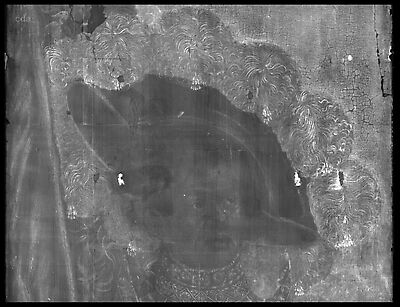

Further clues concerning authorship have been derived by examining Saint Maurice with infrared reflectography. Comparing the underdrawing (fig. 64) with the final painted layers revealed how many decorative details were added at a late stage. Among these are Charles V’s insignia on the pauldrons, the Golden Fleece at the neck, the jewels on the borders of the pauldrons and the tasset of the armor, the jewels of the gorget, and the decoration of the sword handgrip. In fact, some decorative features in the more exact underdrawing were misunderstood in the process of painting. In certain places, the underdrawing follows the original model — whether the illumination in the Hallesches Heiltumsbuch or the reliquary itself — more closely than the final painted form does. For example, the underdrawn flutes adorning the breastplate take into account the rounded form of the chest, but the painted ones do not. The drawing of the tassets also acknowledges their convex form, while the painter made these lines run straight across the curved form. In many places, such details indicate that an artist with a better understanding of form carried out the preliminary underdrawing, while another painted the final decoration on the armor. If Saint Maurice is compared with the Museum’s painting of Judith and Holofernes (cat. 13) from about 1530, it is quite apparent that Judith’s decorative collar exhibits an understanding of the reflection of light and form that surpasses that shown in the saint’s gorget, which is clearly the product of less sophisticated handling.

A comparison of the underdrawing in the flag here with that of the saint’s draperies in The Martyrdom of Saint Barbara (cat. 9) reveals in both a spontaneous, free sketching method in brush and a finely detailed execution that are characteristic of Cranach’s best works.

The same sense of assurance and directness in the handling and execution of Saint Maurice’s face is found in the works most reliably attributed to the master, including Saint Barbara (compare figs. 64 and 44). Certainly, the detailed rendering of Saint Maurice’s face and the masterful treatment of the landscape (the subtle use of color to suggest atmosphere and the reddish tones of the sunset) reflect a level of execution above that displayed in the treatment of the armor.

In the case of Saint Maurice, Cranach’s hand is most likely seen primarily in the design stages and only to a restricted degree in the paint layers. The tedious, painstaking execution of the decorative details of the armor was surely turned over to an assistant, as was typical of the organization of the workshop at the time. Which assistant was given the task may become clearer with continued investigations of the Cranach workshop.

[1] Hamann 2006, p. 291. Later accounts are found in the writings of Gregory of Tours and Alcuin and in the Anno Lied (1080), the twelfth-century Chronicle of Otto of Freising, and various texts of the thirteenth century, including The Golden Legend, the Lower Saxon World Chronicle of Eike of Repgow, and the World Chronicle of Jansen Enikel (Herzberg 1936/1981, pp. 10 – 13).

[2] Seiferth 1941, pp. 371 – 72; Suckale-Redlefsen 1987, p. 29.

[3] Herzberg 1936/1981, pp. 74 – 75; Suckale-Redlefsen 1987, pp. 31 – 33; Hamann 2006, p. 294.

[4] Hamann 2006, p. 312. See also Devisse 2010.

[5] Suckale-Redlefsen 1987, p. 83.

[6] Miedema 2006, pp. 277 – 78.

[7] For a reconstruction of the altarpieces in situ, based on extant panels and on preparatory drawings of the now-lost panels, see Halle an der Saale 2006, vol. 1, p. 29; Tacke 2006, especially the illustration on p. 194.

[8] A reliquary calendar of about 1450, which matches a relic of a saint with each day of the year, came into Albrecht’s collection at the beginning of the sixteenth century. See Anne Schaich in Halle an der Saale 2006, vol. 1, p. 96, no. 29, ill. p. 98.

[9] One complete copy of the 1520 Heiltumsbuch has survived (Stuttgart, Württembergische Landesbibliothek, R 16 Vor 1; 122 pages with 237 woodcuts by Wolf Traut from Nuremberg and possibly two other anonymous artists) in addition to two incomplete exemplars (Nuremberg, Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Hof 135Q, and Halle, Marienbibliothek, Schw 7Q). See Cárdenas 2006, p. 240.

[10] Hofbibliothek Aschaffenburg, Sign. Ms. 14.

[11] Liber ostensionis, 1526 – 27, with later additions; 428 parchment folios with colored full-page illustrations of the objects.

[12] The Saint Maurice was exhibited only once, in Berlin in 1906. After its sale at a Parke-Bernet auction in 1946, it disappeared from view until it surfaced again in 2004 in the Eva Kollsman Collection in New York.

[13] The illumination of the Saint Maurice reliquary statue is on folio 227v, with a descriptive text on folio 228r (Suckale-Redlefsen 1987, pp. 89 – 91; Nickel [Heinrich L.] 2001, p. 253; Ursula Timann in Halle an der Saale 2006, vol. 1, pp. 92 – 94, no. 27, ill.). Jean Louis Sponsel noted that a wooden model had to have been made for the reliquary statue and suggested that Peter Flötner produced this. He also theorized that since the statue was executed between 1522 and 1526, Melchior Baier, a master in Nuremberg by 1525, may have made it (Sponsel 1924, pp. 172 – 73). The silver reliquary statue was melted down in 1540 in Nuremberg to pay off some of Albrecht of Brandenburg’s substantial debts (mentioned by Albrecht in a letter of May 15, 1541, to the chapter of Magdeburg; Redlich 1900, appendix 36a, p. 157).

[14] Gude Suckale-Redlefsen (1987, pp. 221 – 22) alternatively believed that the Metropolitan painting served as the model both for the drawing of the reliquary statue in the Hallesches Heiltumsbuch and for the painting of the figure in the Marktkirche in Halle. The Marktkirche Saint Maurice is usually attributed to Simon Franck (see Tacke 1992, pp. 41 – 71, especially p. 49; J. C. Smith 2006, pp. 30 – 31).

[15]“Your Eminence must also know that in the tall silver Maurice, which stands in the choir in a tabernacle before the high altar, there is a multitude of relics, too many to enumerate.” Hallesches Heiltumsbuch, fol. 228r.

[16] Suckale-Redlefsen 1987, pp. 61 – 63; Nickel (Heinrich L.) 2001, p. 352, fol. 3v; Cárdenas 2006, pp. 264 – 67.

[17] Albrecht had helped to procure the election of Charles and served as his loyal associate. In return, the emperor supported Albrecht’s opposition to the Reformation. The town of Halle and the Neues Stift were placed under the emperor’s protection and further endowed with their own coat of arms and generous stipends.

[18] Examples are illustrated in Halle an der Saale 2006, vol. 1, pp. 166 – 67, no. 79 (entry by Thomas Schauerte), ill. p. 169, and pp. 173 – 76, no. 84 (entry by Andreas Tacke).

[19] For example, the half-armor by Christian Schreiner the Younger (active 1499 – 1529), Austrian (Innsbruck), ca. 1505 – 10, MMA 1991.4, may be compared with that in the Saint Maurice painting, with regard to the fluting on the breastplate, the general (i.e., square) outline of the tassets, and the Klammerschnitt or fauld (the decorative cut on the waist defense). See also the following suits of armor in the Hofjadg-und Rüstkammer, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna: that of Eitel Friedrich II, Count of Hohenzollern, possibly by Kolman Helmschmid, German (Augsburg), ca. 1510, no. A 240; that of Andreas, Count of Sonnenburg, by Helmschmid, ca. 1505 – 10, no. A 310; and that of Bishop Matthäus Lang von Wellenburg, attributed to Konrad Seusenhofer, Austrian (Innsbruck), probably 1511, no. A 244. I am extremely grateful to Dirk H. Breiding, Assistant Curator, Department of Arms and Armor, MMA, for calling my attention to these examples and for discussing issues relating to the arms and armor in Saint Maurice in detail over a period of months. A future publication by Breiding will elaborate on the details of the armor depicted and the implications of these observations.

[20] For an illustration, see Nienholdt 1961, p. 39, fig. 31.

[21] J. C. Smith 2006, p. 30.

[22] A drawing of Emperor Maximilian I in armor (formerly in the W. Baillie-Grohman Collection, Schloss Matzen, Tirol, but whereabouts currently unknown) is inscribed on the reverse, according to Hermann Warner Williams Jr. (1941), Maximilianus I Imperator and below, Visierung Kaysz M[. . .] / silbern Harnasch (Drawing Emp[eror] M[aximilian] / Silver Armor). The armor depicted in the drawing is contemporary with and similar to Saint Maurice’s. However, there are also differences, and Dirk Breiding believes that the drawing may have been for a lifesize statue of Maximilian I, a theory that he is developing further for publication.

[23] Parke-Bernet1946, p. 20, no. 36B. Jean Devisse mentioned the Metropolitan painting as a replica of the Marktkirche example (Devisse 2010, p. 283, n. 286).

[24] Suckale-Redlefsen 1987, pp. 221 – 22, no. 105.

[25] Tacke 2006, p. 211.

[26] On this specific issue, see Schölzel 2005; Heydenreich 2007b, pp. 289 – 318, 323 – 27.

[27] Sandner in Eisenach 1998, pp. 83 – 95.

[Ainsworth, Cat. New York 2013, 73- 77, 289, 290, No. 16]

![Altarpiece of the Virgin [inner movable wing, left]: St Maurice [recto]; St John [verso]](https://lucascranach.org/imageserver-2022/DE_MKH_NONE-MKH001b_FRSup006A/01_Overall/DE_MKH_NONE-MKH001b_FRSup006A_1994-03_Overall-s.jpg)