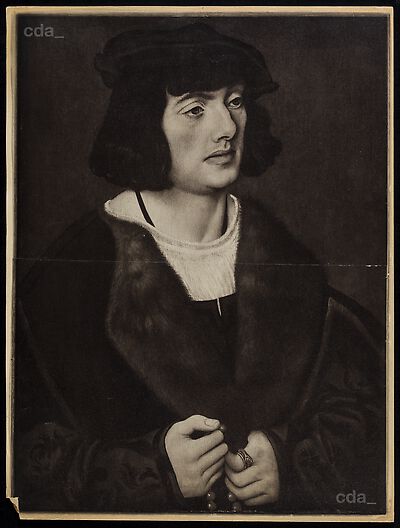

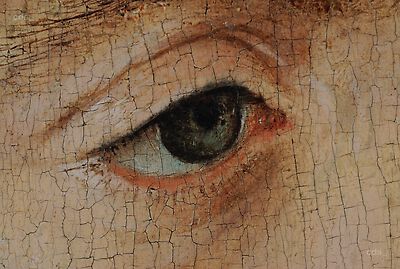

Initially expressing some hesitation, Max J. Friedländer was the first to link this panel to the authorship of Lucas Cranach the Elder.[1] He pointed out that the large curves and heavy shadows of the head are similar to those found in the portraits in the Torgau (Holy Kinship) Altarpiece of 1509 (Städel Museum, Frankfurt) and supposed that the panel could have been painted during Cranach’s trip to the Netherlands in 1508.[2] By the time of Friedländer’s 1932 Cranach monograph with Jakob Rosenberg, there was no further doubt about the attribution, which has been accepted ever since.[3]

In 1966 Dieter Koepplin first proposed this portrait as the pendant of the Portrait of a Woman in Prayer, a work that also represents on its reverse a niche containing a grisaille statue of a saint, Catherine of Alexandria (CH_KHZ-KMB_Dep24).[4] Except for the fact that the female portrait is cut at the bottom by about 5 centimeters, the two panels match closely in size; they also share a similar green background, even though these colors have shifted in differing ways.[5] There was most likely a central panel, twice the width of the two donor panels that, when closed, would have revealed the grisaille images.[6]

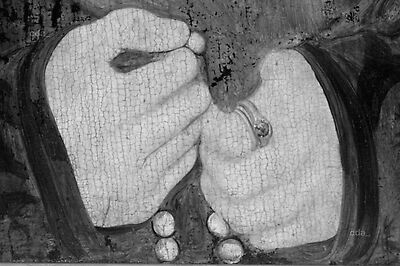

The saints, probably also by Cranach’s own hand,[7] are likely the patron saints of the man and woman, who therefore might be a Peter(?) and a Catherine.[8] Other clues to the identity of the sitters appear in the costume of the woman, who wears a Dutch hood, and in the man’s ring, which bears the coat of arms of the Dutch family Six van Hillegom or Six van Oterleek.[9] Also of note is the fact that the panel is made of Baltic oak, the customary support for paintings produced in the Netherlands and one that was used only rarely by Cranach and his workshop.[10] These factors, as well as the probable original format as the wings of a typical Netherlandish triptych, suggest that the sitters were from the Low Countries and that the male portrait and its pendant may have been painted there. But when and where might this have happened? Cranach visited the Netherlands in 1508, perhaps for political and commercial business on behalf of the Elector of Saxony, Friedrich the Wise; according to Walther Scheidig, he may even have traveled there earlier, in 1506.[11] Two payments in 1508 to the artist and an assistant, “maistre Christoffele,” for unspecified work in Malines for Margaret of Austria, Regent of the Netherlands, indicate Cranach’s connections at the highest court levels.[12] Werner Schade and Koepplin both recognized the strong influence of Netherlandish paintings on Cranach’s works after 1509,[13] and Bodo Brinkmann rightly observed that an “increased empathy” for the sitters comes directly from Cranach’s exposure to the works of the great Netherlandish masters, from Jan van Eyck to Quentin Metsys.[14] The few painted portraits by Cranach from 1509 provide insufficient material for stylistic comparisons,[15] but, as Friedländer pointed out early on, there are close comparisons with the Torgau Altarpiece.[16] It is above all on the basis of the telltale signs of Cranach’s typical technique and execution (see technical notes above) that the attribution to him may be secured. All in all, the extant evidence strongly suggests that Cranach painted this portrait and its pendant while on a trip to the Netherlands in 1508.

[1] Friedländer 1916, col. 132.

[2] Friedländer 1919, p. 84.

[3] Friedländer and J. Rosenberg 1932, p. 39. For the most recent affirmation of the attribution to Cranach, see Bodo Brinkmann in Frankfurt and London 2007 – 8, p. 138, nos. 12, 13; Guido Messling in Brussels and Paris 2010 – 11, p. 138, no. 60.

[4] Koepplin, unpublished opinion, August 12, 1966 (curatorial files, Department of European Paintings, MMA). Koepplin published this observation in 1972, p. 347, and was later supported by Angelica Dülberg (1990, pp. 85, 261). As early as 1919, Friedländer had proposed (p. 85) that the Zürich portrait was linked to one of a man as part of a diptych or the wings of a triptych, but he had not yet identified the exact pendant. The 1978 edition of Friedländer and Rosenberg unfortunately did not take into account Koepplin’s discovery that the Zürich and New York panels are pendants; it dated the former as about 1508 – 10 and the latter as about 1510 – 12 (Friedländer and J. Rosenberg 1978, p. 74, no. 27).

[5] The background of the Metropolitan’s portrait is now a duller, darker green than that of the Zürich portrait, which is a cooler shade of the same color. This has likely resulted from differences in the preservation and conservation of the paintings after they were separated at an early date.

[6] Efforts to discover the central panel have not been successful. Koepplin (in Basel 1974, vol. 2, p. 682) suggested as a possible model the half-length holy figures of the Virgin, Christ, and Saint John in Rogier van der Weyden’s Braque Triptych (Musée du Louvre, Paris).

[7] Koepplin (in Basel 1974, vol. 2, pp. 682 – 83) related the grisaille images to figures in a woodcut from the 1509 Wittenberger Heiltumsbuch (see Basel 1974, vol. 1, p. 417, fig. 233) and to saints from the wings of the Martyrdom of Saint Catherine Altarpiece of 1506 (National Gallery, London; middle panel in Gemäldegalerie, Dresden).

[8] Maryan W. Ainsworth in New York 1993, p. 55.

[9] Wehle and Salinger 1947, p. 200.

[10] Heydenreich 2007b, p. 48. Heydenreich also pointed out that the wide beveling on the reverse corresponds to that found on many sixteenth-century "Dutch" panels (Heydenreich 2002, vol. 1, p. 35 and n. 46) and cited Wadum 1998, pp. 160 – 61.

[11] Scheidig’s assertions are based on evidence in the Weimar Staatsarchiv. See Scheidig 1972, p. 301. The Netherlands trip is known mainly because of Dr. Christoph Scheurl’s dedicatory epistle to Cranach in his oration of December 16, 1508, subsequently published in 1509 (for a German translation of the Latin original, see Lüdecke 1953, p. 51). Scheidig doubted, however, that Cranach produced any paintings on this trip (Scheidig 1972, p. 302). On the trip itself, see also Koepplin 2003b, sec. 4.2, “Warum reiste Cranach 1508 in die Niederlande?,” especially pp. 60 – 67; Schade 2007; Borchert 2010a.

[12] See Duverger 1970, p. 9; Schade 1974, pp. 28, 404, no. 52. The document is to be found in Lille, Départementales du Nord, Namelijk van de Rekeningen van Margareta van Oostenrijk, Gehouden door haar Tresorier Diego Flores, B 19167 Bl. 53.

[13] Schade saw this influence especially in prints after 1509 and in the grisaille wings of the Torgau Altarpiece, which was painted in Wittenberg in 1509 (Schade 1980, p. 28), and suspected that Cranach may have met Hieronymus Bosch and even more likely Quentin Metsys in Antwerp (Schade 1980, p. 30). Koepplin recognized the influence of Jan Joest’s Kalkar Altarpiece on Cranach’s 1509 woodcut The Betrayal of Christ (Koepplin in Basel 1974, vol. 2, pp. 472 – 73). Although he compared the Last Judgment triptychs of Bosch and Cranach, Dirk Bax did not specifically discuss Cranach’s trip to the Netherlands (see Bax 1983). Jozef Duverger doubted any diplomatic purpose for Cranach’s trip (see Duverger 1970, esp. pp. 8 – 13). According to Franz Matsche (1996, p. 38, n. 39), the idea that Cranach served as a diplomat for Friedrich the Wise came from Heinrich Lilienfein (1942, p. 21).

[14] Brinkmann in Frankfurt and London 2007 – 8, p. 138, nos. 12, 13.

[15] Examples include the diptych Johann the Constant and His Son Johann Friedrich (National Gallery, London), Christoph Scheurl (private collection, Nuremberg), and Georg Spalatin (Museum der Bildenden Künste Leipzig), the latter two damaged and heavily restored.

[16] Friedländer 1919, p. 84.

[Ainsworth, Cat. New York 2013, 45, 46, 284, No. 8]