- Attributions

-

Lucas Cranach the Elder

Circle of Lucas Cranach the Elder

Attributions

| Lucas Cranach the Elder | [Cat. New York 2013, 47, No. 9] [1][Cat. New York 2013, 47, No. 9] |

| Circle of Lucas Cranach the Elder | [Schade 1974, 46] |

'Swabian artist' |

- Production date

- about 1510

Production date

| about 1510 | [Cat. New York 2013, 47, No. 9] |

- Dimensions

- Dimensions of support: 153.7 × 138.1 × 1.1 cm (60 1/2 × 54 3/8 × 7/16 in.)

Dimensions

Dimensions of support: 153.7 × 138.1 × 1.1 cm (60 1/2 × 54 3/8 × 7/16 in.)

Dimensions of painted surface: 152.1 × 134.6 cm (59 7/8 × 53 in.)

[Cat. New York 2013, 47, No. 9]

- Signature / Dating

None

- Inscriptions and Labels

Heraldry / emblems:

- at lower right: coat of arms of Rem / Rehm family, Augsburg (black ox on yellow shield; …

Inscriptions and Labels

Inscriptions, Badges:

Heraldry / emblems:

- at lower right:

coat of arms of Rem / Rehm family, Augsburg (black ox on yellow shield; helmet surmounted by black ox standing on yellow pillow) [1]

[1] See Siebmacher 1605-9, pt. 1 (1605), pl. 207; Siebmacher 1856-1967 (ed.), vol. 2, pt. 1 (1856), p. 105, pl. 128; Rietstap 1950 /1972, vol. 2, p. 540; E. Zimmermann 1970, no. 4232. The Hebrew word reem means 'wild ox.'

[Cat. New York 2013, 47, 284, No. 9]

- Owner

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

- Repository

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

- Location

- New York

- CDA ID

- US_MMANY_57-22

- FR (1978) Nr.

- FR021

- Persistent Link

- https://lucascranach.org/en/US_MMANY_57-22/

- at lower right: coat of arms of Rem / Rehm family, Augsburg (black ox on yellow shield; …

Provenance

- Dorfkirche, Goseck, near Naumburg (sold to Zech-Burkersroda)

- Grafen von Zech-Burkersroda, chapel of Schloss Goseck, Goseck (possibly from 1840, definitely by 1844); by descent in Zech-Burkersroda family, Schloss Goseck, later Munich (until 1956)

- sold by either Margarethe, Gräfin von Zech-Burkersroda, or her sister-in-law Baronin Elisabeth, Gräfin von Zech-Burkersroda, to Böhler

- [Böhler, Munich, from 1956]

- [Hougershofer, Zürich; sold to Rosenberg & Stiebel]

- [Rosenberg & Stiebel, New York, until 1957]

- [sold to MMA] Rogers Fund

[Cat. New York 2013, 47, No. 9]

Literature

| Reference on page | Catalogue Number | Figure / Plate | |||||||||||||||||

| Cat. New York 2013 | 47-51 | No. 9 | |||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Exhib. Cat. Prague 2005 | 54 (English version 25) | under no. 5 | |||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Cat. New York 1995 | 219 | Fig. | |||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Erichsen 1994 B | 181, 185, Fn. 8 | ||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Faure 1993 | 95 | Fig. p. 77 (detail) | |||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Cat. New York 1980 | 36 (Vol. 1) | Fig. p. 295 (Vol. 2) | |||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Schade 1980 | 46, 382, Fn. 274 | ||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Friedländer, Rosenberg 1979 | No. 21 | ||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Exhib. Cat. Basel 1974/1976 | 550, 552 | 413 (u.) | |||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Schade 1974 | 46, 382, Fn. 274 | ||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Schade 1972 B | 149-150 | ||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Rosenberg 1960 | 35 | under no. A7 | |||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Metropolitan Museum 1957 | 63 | Fig. p. 42 | |||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Hoppe 1930 | 99 | ||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Bergner 1909 | 125-126 | No. 2 | |||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Lindau 1883 | 242 | ||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Sturm 1861 | 113 | ||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Lepsius 1855 A | 149- 157 | ||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Keller 1853 | 361 | ||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Schuchardt 1851 C | 68 | 314 | |||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Sturm 1844 | 10-11 | ||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

Research History / Discussion

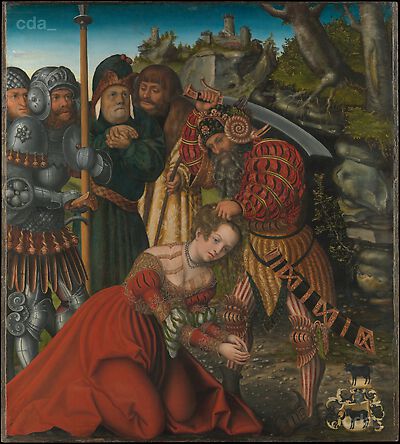

Karl Peter Lepsius suggested that this painting collapses the traditional narrative, simultaneously representing the judge's execution order, the soldier's preparing to draw his sword to carry out the punishment, and Dioscorus’s sudden action, seizing his daughter to kill her himself.[1] This could explain why the man in the yellow robe speaks into the ear of the judge, rather than attending to the action at hand, and also why the judge and two soldiers appear troubled.[2] A similar mood pervades a Cranach-workshop drawing (fig. 40), in which the judge presses his hand to his heart and confers with his companion.[3] However, in a Cranach woodcut of about 1510 – 15 (fig. 41), a large crowd recoils in horror while the judge seems to argue with Dioscorus. A second drawing of around 1513 (fig. 42) shows an even more tightly edited grouping of figures behind Dioscorus that is similar to those in the Museum's painting.[4] In the painting and both drawings, Barbara appears to accept her fate calmly, whereas in the woodcut she is clearly terrified.

Following the details of the legend, all these examples set the scene in a landscape; the Museum's painting and one of the previously mentioned drawings (see fig. 40) show towers on the background hills, indicating Barbara's place of confinement. In the painting, the tower at the far left has three windows in its upper portion, perhaps representing those that Barbara told her father referred to the Trinity.

The beheading itself takes place before the entrance to the cave in which Barbara had hidden; another cave, at the foot of the rocky hills in the background, is the one that Barbara used to escape captivity by fleeing through it onto a mountain.[5] The two trees at the upper right suggest those forked trees between which, in another version of the legend, the judge sentenced Barbara to hang.[6]

Karl August Gottlieb Sturm was the first to mention the Museum’s painting, in 1844, when it was in the chapel at Schloss Goseck, but he misidentified the subject as the Sacrifice of Jepthah’s Daughter.[7] In 1851 Christian Schuchardt named the scene correctly and deemed the painting a product of the Cranach workshop based on Cranach’s woodcut of about 1510 – 15 (see fig. 41).[8] The first comprehensive study of the panel by Lepsius, published posthumously in 1855, discussed the details of the Saint Barbara episode and revealed that the painting curiously had been affixed to the ceiling of the Goseck parish church before it was bought by Count von Zech-Burkersroda and transferred to the chapel at Schloss Goseck.[9] Lepsius determined that the coat of arms at the lower right was that of the Rem / Rehm family, merchants in Augsburg who worked in the Welser-Vöhlin, Höchstetter, and Fugger companies.[10] On that basis, he supposed that the painting originally hung in the Rem residence at Augsburg and that it was likely painted by a Swabian, not a Saxon, artist.[11]

Opinion continued to be divided concerning the attribution and subject matter of the painting,[12] until in 1956 Ernst Buchner affirmed the attribution to Cranach and dated the work around 1509 – 15.[13] Citing the comparison with the coat of arms on the Lucas Rem Altarpiece by Quentin Metsys (Alte Pinakothek, Munich), he identified the one here as probably that of Lucas, who was based in Antwerp. Buchner proposed that Cranach received the commission from Lucas during his trip to the Netherlands in 1508.[14] Modern scholarship has vacillated between those who considered Saint Barbara a work by a talented pupil (Werner Schade and Johannes Erichsen)[15] and those who supported the attribution to Cranach (Dieter Koepplin, who later expressed doubt, and Max J. Friedländer and Jakob Rosenberg).[16] Friedländer and Rosenberg dated the painting to about 1510, pointing out its similarity to Cranach’s early style, as exemplified by Fourteen Helpers in Need (see fig. 43).[17]

The coat of arms is indeed that of the large Rem family, of whom the best known is Lucas, author of a diary covering the years 1494 – 1541.[18] Although it is tempting to identify Lucas as the one who commissioned Saint Barbara, this cannot be established with certainty. The other works commissioned by him, including one painting by Metsys and three by Joachim Patinir, all carry Lucas’s personal motto, Istz gvot so gebs Got (All good things come from God), which is absent from the Museum’s painting.[19] Equally uncertain is why Lucas would have commissioned a Martyrdom of Saint Barbara, although he was related to two Barbaras by marriage through his wife, Anna Ehem.[20] If the painting originally had wings, forming a triptych, these might offer further clues about the commission, but no clear candidates have survived.[21] Two smaller workshop copies of the painting survive as independent panels and testify to the popularity of the image.[22] Of the many earlier representations of the subject, the one that most directly inf luenced the Museum's painting seems to be Master MZ's engraving of about 1500.[23] The painting closely follows the poses of the two main protagonists in the print.[24] The preparatory drawings mentioned above (see figs. 40, 42) experiment with a number of tightly edited, close-up renderings of the figures that achieve a more subtle expression of emotion than Cranach had realized in his woodcut from about 1510 – 15 (see fig. 41).

In its compact, friezelike arrangement of figures parallel to the picture plane, the Museum's Saint Barbara has much in common with several Cranach paintings dating to about 1510. Gunnar Heydenreich has noted its similarity to the painted wings of the altarpiece in the Stadtkirche Sankt Johannis in Neustadt an der Orla (dated 1511 – 12 on documentary evidence), which share compressed figures in the foreground, a cloudless sky, and certain anatomical awkwardnesses.[25] Also stylistically related are the large Virgin and Child (Samuel H. Kress Collection, University of Arizona Museum of Art, Tucson) that once formed the centerpiece of a triptych with wings of Saint Catherine and Saint Barbara (Moravská Galerie, Brno), which Friedländer and Rosenberg dated to about 1513, as well as the Virgin with Child Eating Grapes of about 1509 – 10 (Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid).[26] The faces of Saint Barbara and the Virgins in the Tucson and Madrid paintings are especially close in type and in their smooth, pinkish flesh tones. These paintings also display the same compressed space, with figures in the foreground, and similarly painted background castles, rocky outcroppings, trees with lichen, and bushes with yellow-tipped leaves.

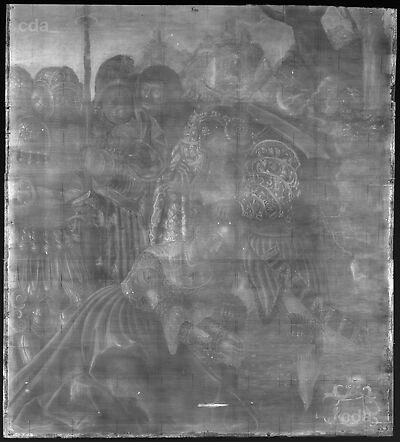

A less planar sense of space and a more graceful integration of figures within that space characterize other paintings from the same period that are securely attributed to Cranach. Among these are The Martyrdom of Saint Catherine of about 1505 (Collection of the Reformed Church, Budapest), the Saint Catherine Altarpiece, inscribed and dated 1506 (Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden), and the Torgau Altarpiece, signed and dated 1509 (Städel Museum, Frankfurt).[27] Since some scholars have therefore questioned the attribution of Saint Barbara to Cranach, it is important to compare the panel with Fourteen Helpers in Need, which has generally been dated between 1505 and 1509 (fig. 43).[28] In particular, the face of the armored soldier, second from left in the former, is quite similar to that of Saint Pantaleon in the latter; the faces of the two armored men at the far left in both paintings are also comparable, especially in terms of physiognomic details. The armor is similarly rendered in each painting: broad strokes of the brush in white are scored through to create the sharp black lines defining its structure. A comparison of the underdrawing of the heads in the two paintings revealed a reliance on short, curved strokes, sometimes seeming to be randomly applied, to indicate facial features or to suggest garment folds.[29]

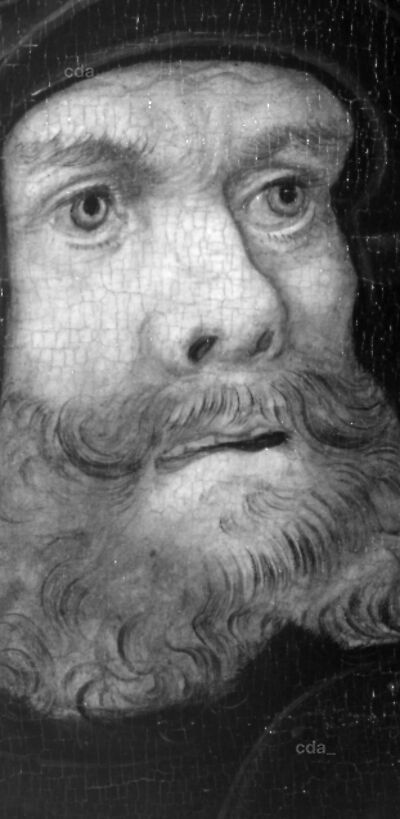

The same characteristics are also evident in the drawings attributed to Cranach from about the same time, especially The Beheading of Saint Barbara of about 1513 (Nationalgalerie, Oslo), Saint Anthony in a Niche of about 1509 – 10 (Harvard Art Museums, Fogg Museum, Cambridge, Massachusetts), and Samson Fighting the Lion of about 1509 – 10 (Kupferstich-Kabinett, Dresden).[30] Finally, the faces in Saint Barbara are treated in a combination of ways (fig. 44). X-radiographs revealed that some, including that of the judge, have a 'marked virtual relief,' as Heydenreich called it,[31] others a softer, more blended approach, as seen in that of the man in yellow damask.

Such variations may reflect the change that Ingo Sandner noted in Cranach’s style around 1510, which was due perhaps to his contacts with Franconian painting or to his trip to the Netherlands in 1508.[32] When taken together, these observations suggest that Saint Barbara can be dated to about 1510, at a moment when Cranach not only was looking to further streamline his painting methods but also was influenced by practices elsewhere in developing facial types and expressions.

[1] Lepsius 1855, p. 151.

[2] In the paint layers, the eyes of the man in the yellow damask robe were shifted toward the judge, whereas in the underdrawing they were directed toward Dioscorus.

[3]The location of this drawing is currently unknown. Although scholars (Theo Ludwig Girshausen and Jakob Rosenberg) have considered it a workshop production, possibly even a counterproof, with Dioscorus standing with sword raised behind rather than in front of Barbara, the drawing represents a design stage previous to the solution reached in the Metropolitan’s painting. The handling and execution of the drawing appear labored and weak. However, if it eventually reappears, a careful examination of it in relation to Cranach’s underdrawings may be helpful in regard to the question of attribution. See Girshausen 1937, no. 128; J. Rosenberg 1960, p. 35, no. A7; Hof bauer 2010, p. 462.

[4] Hofbauer 2010, pp. 122 – 23, no. 16582. A comparison of the execution and handling of this drawing with that of the underdrawing in Cranach’s painting shows the same artist at work, as evidenced by the short dashes describing the features of the face, the bold, free contours of the exterior and interior drapery forms, and the quick, nervous scribble connoting landscape and setting.

[5] This detail is specifically mentioned in Der Heiligen Leben, Nuremberg: Anton Koberger, 1488, fol. cclxiii verso, col. 1: “warf sie ynhalb auff einen berg.”

[6] This detail is from the translation of the legend by William Caxton (1483) and is not found in the editions published in Germany before around 1510, such as those in Nuremberg (1488), Cologne (1479), Augsburg (Zainer of 1475). I have not been able to see the Ulm 1488 version.

[7] Sturm 1844, quoted in Lepsius 1855, p. 149.

[8] Christian Schuchardt also noted that the painting was in poor condition and had been restored (Schuchardt 1851 – 71, vol. 2 [1851], p. 68). In 1883 M. B. Lindau agreed that the Saint Barbara woodcut was a “study” for the painting in Goseck, which he considered a workshop product or by a follower of Cranach, similar in style to the altarpiece wings in the east choir of Naumburg Cathedral (Friedländer and J. Rosenberg 1978, p. 158, no. Sup 1F, attributed to the Master of the Pflock Altarpiece; Sandner 1993, p. 302, reassigned to the Cranach workshop). Lindau 1883, p. 242.

[9] Lepsius 1855, pp. 151 – 52 and 149, 156.

[10] Grünsteudel, Hägele, and Frankenberger 1998, p. 742.

[11] Lepsius 1855, p. 152. Lepsius constructed a purely hypothetical provenance for the painting in order to explain its journey from Augsburg to Goseck (Lepsius 1855, pp. 153 – 56).

[12] Unaware of Christian Schuchardt’s publication, Friedrich Eduard Keller (1853, p. 361) attributed the painting to Michael Wolgemut and again referred to the subject as the Sacrifice of Jephthath’s Daughter. Karl August Gottlieb Sturm repeated his assertion of 1844 that the subject is the Sacrifice of Jephthah’s Daughter and agreed with Keller that it is by Wolgemut. He also verified the provenance of the work (Sturm 1861, p. 113). Heinrich Bergner (1909, p. 125) attributed the painting to Cranach but called the subject the Execution of Saint Catherine. Friedrich Hoppe (1930, p. 99) repeated the information in Lepsius 1855, p. 151, and referred to the work only as a large painting representing an Old Testament theme.

[13] Buchner, unpublished opinion, Munich, June 18, 1956 (curatorial files, Department of European Paintings, MMA).

[14] Buchner’s proposal is possible, since both Rem and Cranach were in Antwerp from November 10 to 17, 1508 (Buchner, unpublished opinion, Munich, June 18, 1956, curatorial files, Department of European Paintings, MMA); Rem 1494 – 1541/1861, pp. 10, 108, n. 290; Scheidig 1972, p. 301.

[15] Schade 1972a, pp. 149 – 50; Schade 1974, p. 46; Schade 1980, p. 46; Erichsen 1994, pp. 181, 185, n. 8.

[16] Koepplin in Basel 1974, vol. 2, pp. 550, 552; Friedländer and J. Rosenberg 1978, p. 72, no. 21, ill.

[17] Friedländer and J. Rosenberg 1978, pp. 69 – 70, no. 16.

[18] Rem 1494 – 1541/1861.

[19] Metsys: Altarpiece of the Trinity with the Virgin and Child (Alte Pinakothek, Munich); Joachim Patinir and / or workshop: Assumption of the Virgin ( Johnson Collection, Philadelphia Museum of Art); Rest on the Flight into Egypt (Mrs. G. Kidston Collection, Bristol, England); Saint Jerome in Penitence (Ca’ d’Oro, Venice). For other members of the Rem family who may have commissioned the painting, see notes by Alice Hoppe-Harnoncourt and Joshua Waterman (painting report form, curatorial files, Department of European Paintings, MMA).

[20] Anna Ehem was raised by a Barbara von Dynheim, and her maternal grandmother was Barbara Gres(s)ler (Rem 1494 – 1541/1861, pp. 2 – 3, 46, 52, 56).

[21] One fragment of similar size, style, and date is a single female figure, a Saint Margaret. Joshua Waterman investigated the possibility that this panel could have been the right inside wing joined to Saint Barbara as the central panel, as suggested by its dimensions (93 × 62.5 cm, although cut at the bottom). However, the sky of the Saint Margaret is yellow at the horizon, and thus a poor match for the blue sky of the Museum’s painting. For an illustration, see Weschenfelder 2003, pp. 71 – 72, no. 9, ill. p. 49, fig. 32.

[22] See Gunnar Heydenreich in New York 2009, n.p., no. 1, Workshop of Lucas Cranach the Elder, 1511 – 1514, The Martyrdom of Saint Barbara. One panel, at Lawrence Steigrad Fine Arts, New York, measures 49 × 38.9 cm and was previously owned by D. Heinemann, Munich, 1936; possibly Victor D. Spark, New York, 1971; anonymous sale, Christie’s, New York, January 9, 1981, no. 180; Bob Guccione, New York, until 2007. The other smaller version, possibly from the Cranach workshop, measures 38 × 29 cm and was in the Collection Busch, Mainz, and then subsequently in the Collection Eduard Götzschel, Frankfurt am Main.

[23] Erichsen noted that the stance of Dioscorus in the painting appears to have been borrowed from the print (Erichsen 1994, p. 181).

[24] Illustrated Bartsch 1978 –, vol. 9, pt. 1 (1981), p. 366, no. 9.

[25] Heydenreich, unpublished opinion, May 22, 2002 (curatorial files, Department of European Paintings, MMA).

[26] Friedländer and J. Rosenberg 1978, pp. 78 – 79, nos. 46, 47, p. 75, no. 30.

[27] Ibid., pp. 68 – 70, nos. 11, 14, 18.

[28] Dated about 1505 by Schade (1980, p. 459) and Ingo Sandner (in Eisenach 1998, pp. 87, 103 – 5), about 1507 by Friedländer and J. Rosenberg (1978, pp. 69 – 70, no. 16), and about 1505 – 9 by Iris Ritschel (see Eisenach 1998, p. 87, n. 15).

[29] Heydenreich 2007b, p. 108, figs. 90, 91.

[30] See Hof bauer 2010, nos. 27, 24, 23, respectively.

[31] Heydenreich 2007b, p. 201.

[32] Sandner 1994, p. 188; Heydenreich 2007b, p. 200 (referring to Sandner 1994).

[Ainsworth, Cat. New York 2013, 47-51, 284, 285, No. 9]