The Cranach Altarpiece in the Church of St Wolfgang, Schneeberg

(for a comprehensive evaluation of the altarpiece, its history and iconography see: Pöpper, Thomas [Text]/ Pietsch, Jürgen M. [Photos], Ein ›bildgewordener Kirchentraum‹. Das Reformationsretabel in St. Wolfgang, Schneeberg/Erzgebirge von Lucas Cranach dem Älteren. Introduction by Frank Meinel and a source edition by Dietrich Lücke [= Schätze Mitteldeutschlands, 5], Spröda 2012 [in print]).

Significance

The altarpiece commissioned from Lucas Cranach the Elder, which was installed in the Church of St Wolfgang in Schneeberg in 1539 is not only the most comprehensive and complex altarpiece produced in the Cranach workshop. It also represents the first decorative program in a protestant church in Saxony: the Schneeberg art work is the first Reformation altarpiece; here the theological concept of the Lutheran ‚new faith‘ was represented for the first time on an altarpiece. Thus its significance extends far beyond early and medieval German art. The altarpiece has a European dimension.

Program

Despite – or perhaps because of- its innovative, even momentous content the appearance and technical or liturgical function of the altarpiece refers to pre-reformation patterns. The present metal frame (argentan or nickel silver), which was made in the 1990s allows one transformation or two states, the so-called work day (‚Alltags-‘) and the so-called feast day presentation (‚Festtagsansicht‘). The Last Supper (predella) and the representation of Law and Mercy and a Passion Cycle with portraits of regional rulers are always visible. There is some indication that the original construction of the altarpiece allowed a further transformation and that the present fixed wings of the work day presentation could be closed over the inner wings and the central panel. Such a construction would have made the representation of two Old Testament judgments, namely ‘The Fire of Sodoma’ and ‘The Flood’ visible from the nave (today these scenes are on permanent display on the reverse of the altarpiece).

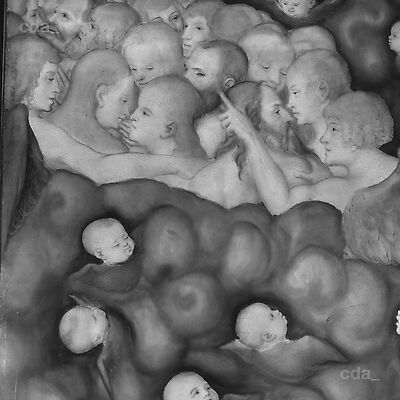

It is certain that the altarpiece could at all times be walked around and viewed from all sides, independent of its state of presentation. This is not only indicated by the elaborate depiction on the reverse of ‘The Enthroned Christ at the Last Judgement’ and ‘The Separation of the Blessed and the Damned’ and the additional sumptuous decoration. Also the fact, that in Schneeberg (officially Lutheran since 1534) the communion was celebrated by walking around the altarpiece (and still is) is a clear indication that it was intended to be freestanding. This means, that the congregation today, as always, walk around the altarpiece between receiving the bread and the wine and can view the admonishing and warning judgement scenes on the reverse from close proximity.

Today there is a panel with an inscription attached to the reverse on the predella beneath the ‚Last Judgement‘. It was added in 1996 and replaces a depiction of ‘The Resurrection of the Dead’, which was directly related to the ‘Last Judgement’. This panel was destroyed by fire on Schneeberg’s ‚Black Day‘ (Schwarzen Tag von Schneeberg), the 19th of April 1945 (a black and white photograph of it still exists).

History

During the Thirty years War (1616 to 1648) Schneeberg was looted twice by imperial troops. The altarpiece was taken apart as a result of the ravages and the panels were stolen. They were taken to Bohemia as a form of security (1633). However the altarpiece could be restored to its former owner (1649) and was soon returned to the Church of St Wolfgang where it was reconsecrated (1650). An inscription, numerous coats-of-arms and some portrait panels were added to complement the original state (two of these additional portraits are preserved in the Schneeberg Museum für bergmännische Volkskunst).

Later, in the 18th century, not only the panels of the altarpiece but also the frame were permanently dismantled. The wing panels and the other panels were sawn into more than a dozen pieces, both lengthwise and perpendicularly to the paint surface. Panels painted on both sides were split to view them side by side. They were hung on the supporting columns of the gallery located at the east end of the church like paintings in a museum. We can only roughly estimate the extent to which the size of single panels was adjusted and the edges trimmed. However these losses are probably negligible and can be discounted. Some of the fragmentary panels – the central Crucifixion and the predella depicting the Last Supper- were integrated into a baroque altarpiece (set up between 1709 and 1712; destroyed in 1945). A depiction of ‘The Miracle of Pentecost’, which is only documented in written sources appears to have been lost during this by no mean for the 18th century untypical modernization, and despite all reasonable care taken by the department of monument preservation. To date there is no trace of the painting.

Later the (temporary) transfer of two wing panels to the collection in Dresden (Dresdener Kunstsammlungen) proved to infringe less on the coherence of the program, and more on the inventory (1929); in Schneeberg the missing panels were replaced by copies (1933). The altarpiece suffered irreparable damage during the Second World War. On the above mentioned day in April in the year 1945 the town was bombed and St Wolfgang’s caught fire. Courageous citizens risked their lives to save almost all of the panels from the fire, which shortly after raised the church building to the ground. Among the Cranach paintings only the reverse of the predella depicting the ‘Resurrection of the Dead’ was destroyed.

It was not until 1996 that the restored altarpiece – including the wing panels from Dresden, in a modern metal frame and with a new sequence of transformation – could be reconsecrated in the reconstructed church. This is the condition in which the altarpiece is displayed today – located in the place it was created for over 470 years ago.

Contract

The attribution of the altarpiece to Lucas Cranach the Elder is without question, and not only for stylistic reasons as it is also supported by archival material. The church community’s account book (‚Kastenbuch‘) from the year 1538/1539 records ‚meister lucas maler, zu wittenpergk‘ as unequivocal payee. He acts here – also in legal terms- as the manager of the workshop. The altarpiece was probably produced on the basis of division of labour. Different workshop assistants who cannot be identified with certainty, but also – the most extensive sections- Lucas Cranach the Elder and his son, Lucas Cranach the Younger worked side by side on altarpiece.

In the above mentioned account book there are also grounds for concluding that not the Ernestine rulers portrayed on the altarpiece, but the citizens or the protestant church community commissioned Lucas Cranach the Elder and paid him the handsome sum of 357 Gulden and 3 Groschen.

Conclusion

Despite the recent increase in scholarly interest and published tributes as well as the discovery of important new archival material there remains considerable need for further research (on iconography, who actually commissioned the altarpiece, original presentation, the missing artist’s insignia, but above all the complex question of attribution). It has been established that the Schneeberg altarpiece, which on sight employs ‚catholic‘ visual conventions, first reveals the Lutheran dimensions of the overall concept in its detail, a concept which was later to be developed and radicalized in the altarpieces in Wittenberg and Weimar (1547/1555). As such the St Wolfgang altarpiece in Schneeberg can be viewed both as an experiment or »ein Testfall für die protestantische Bildkunst (a test case for protestant pictorial art) « (Michael Böhlitz 2005) and a record of »allmählichen Übergang[s] von einer katholischen zu einer lutherischen Identität Sachsens (Saxony’s gradual transition from a catholic to a Lutheran identity)« (Jenny Lagaude 2010)

However one inexplicable ‚miracle’ of Cranach’s artwork is that the ‚visualised dream of the church‘ (›bildgewordenen Kirchtraum‹) (described as such in a poem by Kurt Arnold Findeisen [1883 - 1963] ) not only created a pictorial reality for the ‚new faith‘, but was also a symbol of the miners‘ identity and the Erzgebirge homeland, and has still not lost its aesthetic appeal and –hopefully- its religious potency.

[Thomas Pöpper, 2012]

![Altarpiece of St Wolfgang's Church in Schneeberg, Erzgebirge [central panel]](https://lucascranach.org/imageserver-2022/DE_WSCH_NONE-WSCH001A_FR379/01_Overall/DE_WSCH_NONE-WSCH001A_FR379_Overall-s.jpg)

![Altarpiece of St Wolfgang's Church in Schneeberg, Erzgebirge [left wing]](https://lucascranach.org/imageserver-2022/DE_WSCH_NONE-WSCH001B_FR379/01_Overall/DE_WSCH_NONE-WSCH001B_FR379_Overall-s.jpg)

![Altarpiece of St Wolfgang's Church in Schneeberg [right wing]](https://lucascranach.org/imageserver-2022/DE_WSCH_NONE-WSCH001C_FR379/01_Overall/DE_WSCH_NONE-WSCH001C_FR379_Overall-s.jpg)

![Altarpiece of St Wolfgang's Church in Schneeberg, Erzgebirge [left fixed wing]](https://lucascranach.org/imageserver-2022/DE_WSCH_NONE-WSCH001D_FR379/01_Overall/DE_WSCH_NONE-WSCH001D_FR379_Overall-s.jpg)

![Altarpiece of St Wolfgang's Church in Schneeberg, Erzgebirge [right fixed wing]](https://lucascranach.org/imageserver-2022/DE_WSCH_NONE-WSCH001E_FR379/01_Overall/DE_WSCH_NONE-WSCH001E_FR379_Overall-s.jpg)

![Altarpiece of St Wolfgang's Church in Schneeberg, Erzgebirge [predella]](https://lucascranach.org/imageserver-2022/DE_WSCH_NONE-WSCH001F_FR379/01_Overall/DE_WSCH_NONE-WSCH001F_FR379_Overall-s.jpg)